It’s tough work eulogizing a wit as acerbic, clever, and ruthless as the late Gore Vidal. So most of those luminaries who paid him tribute at New York’s Schoenfeld Theater on Thursday were content to take the safe route: they quoted him. They read from his essays, performed scenes from his plays, and recited his most quotable quotes. No author could ask for more.

Nor could most audiences, because Vidal, whatever else he was, was an entertaining man who honored the imperative of singing for his supper pretty much wherever he went.

So the audience was regaled with old favorites from the Vidal canon (“Every time a friend succeeds, I die a little.”) and some not heard enough (“I’m exactly as I appear. There is no warm, lovable person inside. Beneath my cold exterior, once you break the ice, you find cold water.”)

Most such memorials take place in august churches. Vidal’s was staged, appropriately, in the Broadway theater where his play, The Best Man, currently is in revival. Decked out in campaign posters, bunting, and the placards with the names of states that get hoisted on the floors of political conventions—all part of the paraphernalia of The Best Man—the “set” of the Schoenfeld underscored the bi—and sometimes trifocal nature of Vidal’s enterprise—he was never strictly, much less merely—a writer, or a performer, novelist, historian, or politician (grandson of a U.S. senator and himself a candidate for both House and Senate, and on opposite sides of the continent, though being merely mortal, not at the same time). He was all those things and usually more than one or two at once.

In an unspoken—and perhaps unintentional—tribute to Vidal’s eclecticism (surely no major author of our time was so equally at home in the pages of The New York Review of Books and the banquettes of the Polo Lounge in the Beverly Hills Hotel), the people who came forth to testify were not literary folk. Most sendoffs for famous authors are mobbed by fellow writers, editors, and critics. That crowd will get its turn later in the fall. But in the meantime, there was plenty of class and gravitas at the beautifully executed Schoenfeld event (a big hat tip to Jeffrey Richards Associates and all who helped mount this thoughtful memorial). This hurrah clearly reflected Vidal’s show-business side.

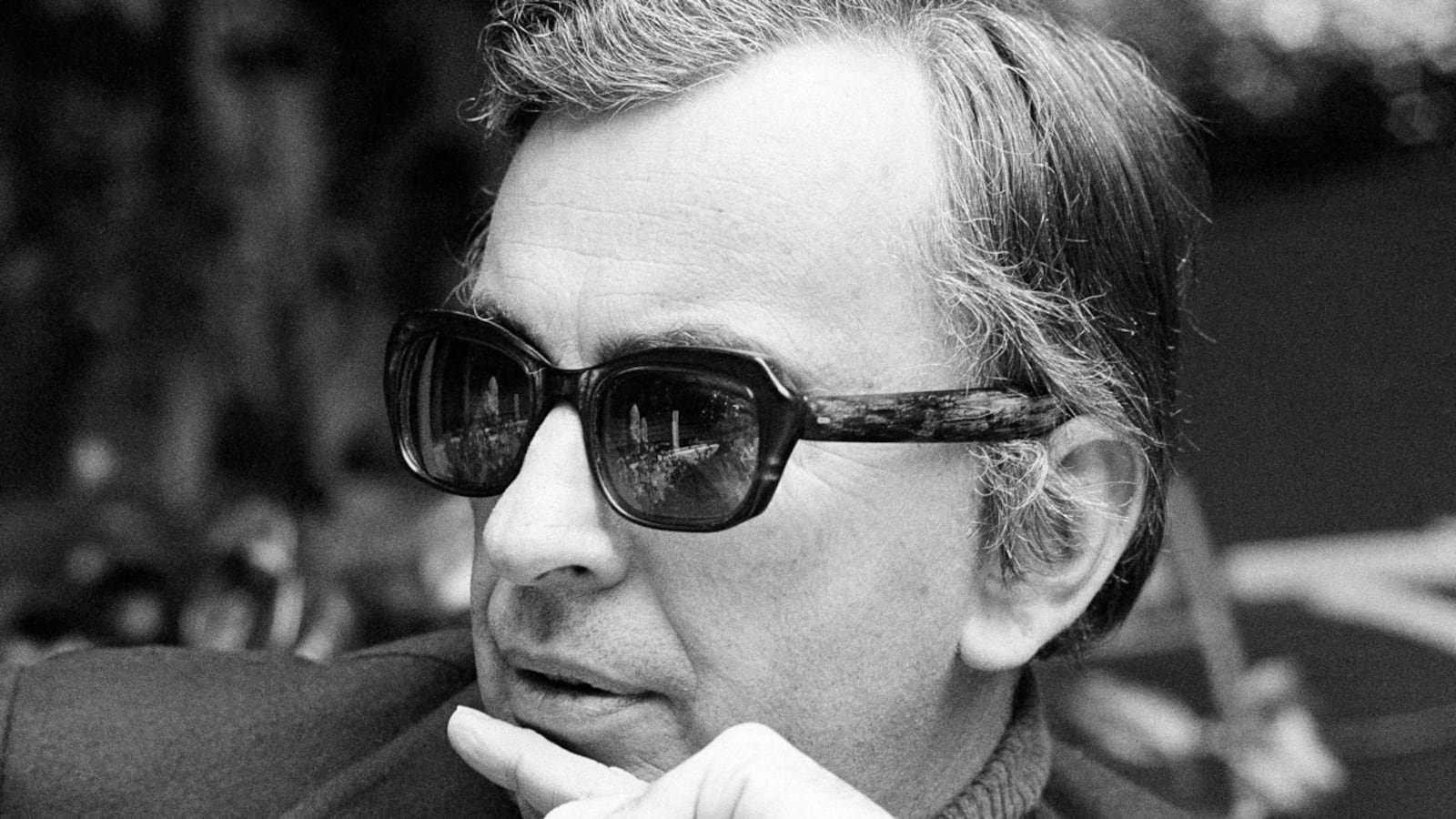

Speaking of sides, there was little to do before the show started but celebrity-spot (Salman Rushdie, Griffin Dunne …) and stare at the enormous photograph of a handsome, middle-aged Vidal that graced the back wall of the stage, a sight prompting the recollection that Vidal, perhaps alone among American authors, knew which side he photographed best from—the left, if memory serves.

Dick Cavett presided with that strange, weirdly charming affect that is peculiarly his—part reflexive TV host, complete with that inverted introduction style so peculiar to television (“We’ve come to the part in our celebration where you’re going to get something absolutely free that’s quite wonderful. But before you do, with some thoughts on Gore as well as a message from David Mamet, here’s Liz Smith…”), and part self-aware personality at war with his own slickness (“And now the best quartet since the Mills Brothers … the Mills Brothers were a quartet, right?”).

After Cavett’s opening monologue, the ever-tart playwright, screenwriter, director, and peerless comic Elaine May led off. She was followed by actors Jefferson Mays and Susan Sarandon, performing a scene from Vidal’s Romulus. Cybill Shepherd read a letter from director Peter Bogdanovitch that included his astonishing recollection of Vidal weeping while reading aloud from one of Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s farewell speeches—Bogdanovich, maddeningly, did not elaborate.

May was followed by actors Jefferson Mays and Susan Sarandon, performing a scene from Vidal’s Romulus. Cybill Shepherd read a letter from director Peter Bogdanovitch that included his astonishing recollection of Vidal weeping while reading aloud from one of Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s farewell speeches—Bogdanovich, maddeningly, did not elaborate.

Alan Cumming and Richard Belzer read excerpts from Vidal essays. Elizabeth Ashley, Christine Ebersole, Candice Bergen, and Angelica Huston—this, by the way, was the aforementioned best quartet since the Mills Brothers—took turns reading assorted Vidal one-liners. Then Ashley remained on stage to tell a very funny story about getting drunk with Vidal and Tennessee Williams, to whom she later confessed that in Vidal’s presence, “I just feel so stupid.” Williams consoled her: “Oh darlin’, never mind, he’s just an old smarty pants.”

Cavett read a warm letter sent by Hillary Clinton. Then Dennis Kucinich, the congressman and former presidential candidate, delivered a funny (“You’ve got to do something about your hair!”) and ultimately eloquent reminiscence about asking Vidal’s advice on a presidential run (“With Gore gone, who shall I call now? I shall still call on him.”).

Michael Moore read from a Vidal essay on American empire and managed to evince a kid’s genuine humility in the presence of one of his heroes when recounting the time he asked for Vidal’s counsel prior to the Oscars, when Moore was nominated for Bowling for Columbine.(“You’ve got to quote Jefferson. No one’s ever quoted Jefferson at the Oscars before.”)

Then, right before the “something absolutely free that’s quite wonderful,” which turned out to be James Earl Jones and John Larroquette performing a scene from The Best Man that was indeed quite wonderful, Liz Smith turned up and in that beguiling Texas drawl that must have coaxed thousands to say more than they meant to, gave everyone a good look into why people adored such a prickly man.

“He loved gossip. He didn’t think I did it well enough, but he became fond of me in spite of my lacks,” Smith said. “Gore would chide me by phone or by letter when I wrote something he didn’t like. His opening was always, ‘Goddamit, Liz.’ He would just let me have it, flattering, cajoling, accusing. I always liked to think he made me and all of us better than we were.

“He was just about the smartest man I ever met, and over time we became real friends. He was privately surprising. He was a kind, gentle person, a unique talker with the great good manners of the last of the true intellectuals, historians and literates.

“Gore had an excellent theory that Federico Fellini’s masterpiece, La Dolce Vita, which excoriated America’s Anglo-Saxon Puritanism, was not really a movie about decadence at all. He said, simply, ‘It is life as it is lived.’ That became my motto. I realized that life is not decadent and so shocking. It’s only life as it is lived.”

That was a sweet, utterly genuine way to bookend the event, which had begun on a slightly forbidding note with Elaine May, who clearly came out nursing a grudge before she settled in and clocked one out of the park.

“Until a couple of days ago, I thought I was the only speaker,” she began. “And then I was told that I only had two minutes. I can’t keep track of two minutes, but I’m going to know probably when my time is up when the music comes on.

“I met Gore Vidal many years ago under the most shocking, never-before-told circumstances, which I can’t tell you now because I don’t have time. Instead I’m going to read some excerpts from an interview that took place after his partner, Howard, died. So he’s a little softer than usual.”

She quoted Vidal going off on Woodrow Wilson (“a conceited, pompous schoolteacher”), and then says, “I wish I had the time to tell you what the slightly more mellow Gore said about Franklin Roosevelt, Truman, the CIA, homosexuality, The New York Times—except for Paul Krugman—the surprisingly liberal domestic policies of Richard Nixon, the stunning revelations about Mickey Rooney, which is really good reading.

“I think if Gore had realized when he did that interview that his memorial would have an award-paced feeling, he would have made his sentences shorter and I would have had some really pithy one-liners.

“But I am going to read this one answer to a question the interviewer asked. He said to Gore, ‘Do you think any president ever acted in good faith, in the overview?’

Vidal’s answer rambled all the way to Chile and the U.S.-backed overthrow of the Allende government in Chile, but wound up with the author saying, “I think that if we acted as though we’d dismissed history and did what is perhaps the right thing to do, it might pay off.”

“Now this is the most fearlessly unsophisticated statement that anyone over the age of 15 has ever made,” May said. “This is really Idealism in capital letters. And I think that this was Gore’s country and he was a real idealist.

“And he was a cynic, because of course all idealists are disappointed and become cynics. But he really had the wit and the energy to conflate that disappointment into outrage. I don’t mean satire or concern or anxiety but really wait-I’ve-gone-too-far outrage. Real outrage. And I think it’s the kind of outrage that I don’t think we have much of in this country. And now, we have less.”