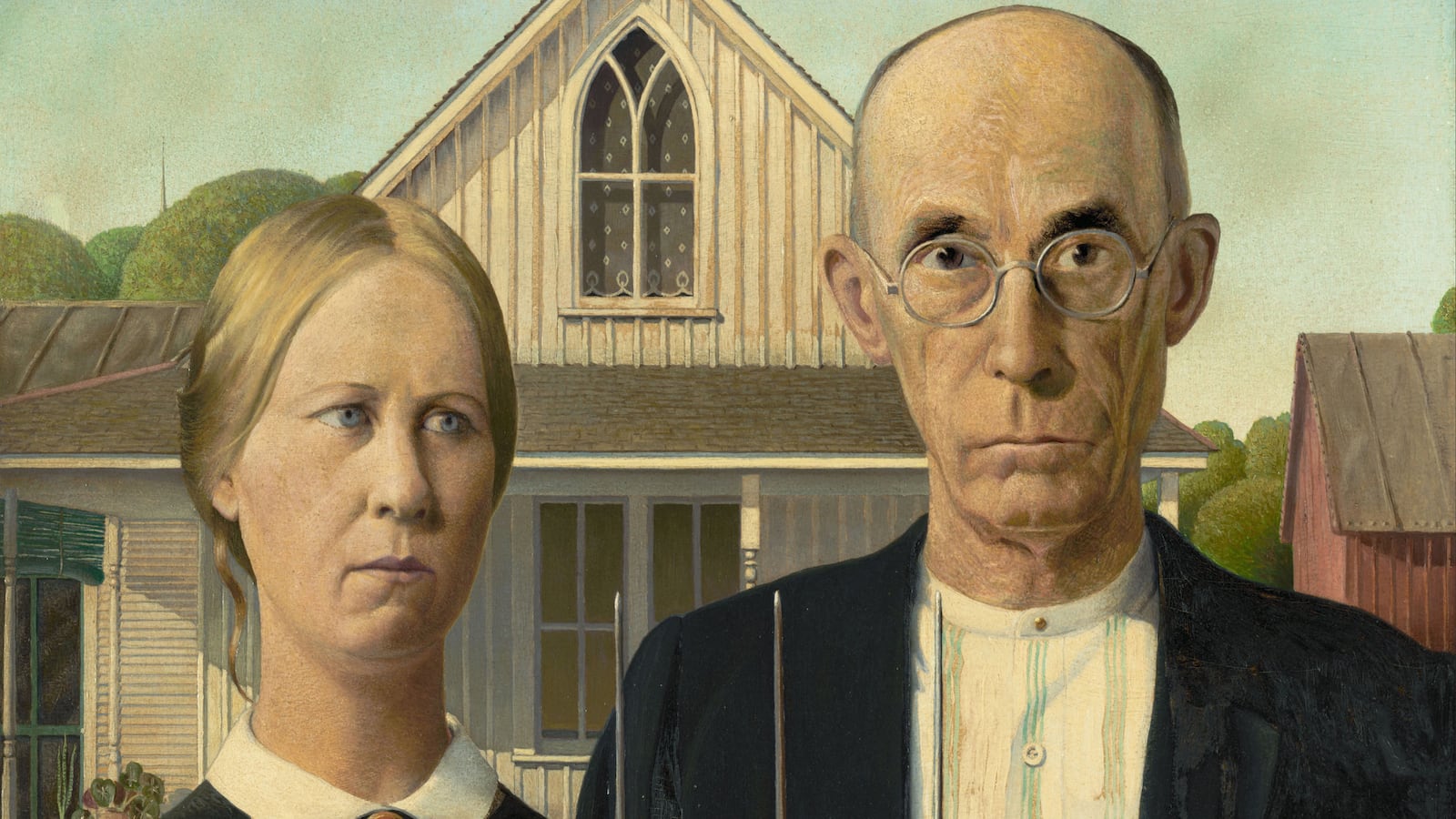

Other than Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” or Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” it would be hard to name a work of Western art that has been more exhaustively reproduced, parodied, pimped, praised, and disparaged than Grant Wood’s painting “American Gothic.” Just about everyone is familiar with its stern Iowa farmer gripping a pitchfork and glaring at the viewer as he stands with his wife (or is it his daughter?) in front of a clapboard farmhouse beneath an unblemished Midwestern sky. And just about everyone misunderstands both the painting and its creator.

So argues the ravishing retrospective that has just opened at New York’s Whitney Museum, Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables. Barbara Haskell, the show’s curator, points out in her catalog essay that Wood’s mature career unfolded during the Great Depression, a time much like our own when “a populist backlash against elitism” led to “tension between urban and rural areas.” This show, as its subtitle suggests, makes the case that the conventional narrative about “American Gothic”—that it came out of Wood’s embrace of the bedrock values of the American heartland—is just one of many misperceptions about the artist, his masterpiece, and his entire body of work.

Many of those misperceptions can be laid on Wood himself, a native of Iowa who was happy to promote himself as a homespun farmer-painter, an artist-in-overalls who embodied the wholesome, virile, patriotic virtues supposedly present in his art. This reading was boosted by an earlier retrospective at the Whitney, Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision, in 1983, when President Ronald Reagan was busy making America believe it was great again by selling his “Morning in America” snake-oil optimism, which Americans bought wholesale because it felt so reassuring after the shocks and convulsions of the ’60s and ’70s. Reviewing the show, the critic Hilton Kramer derided Wood as “a handy instrument for anyone wishing to turn back the cultural clock to the so-called good old days.”

What a difference three decades make. The current Whitney show is less about sunrise than twilight, or midnight. We learn that Wood spoke disparagingly about the “Babbitty” nature of the Midwest and the “gloomy inhibitions” of small-town life there. Far from being an unschooled farmer-painter, he travelled repeatedly to Europe, studying Old Master paintings, mimicking the Impressionists, and leading a bohemian life that would have been unthinkable in the American heartland. He was pudgy, near-sighted, and shy, a deeply closeted homosexual. What it all added up to, in Haskell’s words, was “a conflicted, complex relationship between the artist and the homeland he professed to adore.”

You see the conflict everywhere in the current show. You see it in Wood’s portrait of his mother, in what he described as her “bleak, faraway, timeless” eyes. You see it in “Arnold Comes of Age,” a portrait of Wood’s studio assistant, who appears to ache with a longing for something he’ll never be able to name. You see it in the subversively mocking pictures of Shriners and Daughters of the American Revolution, in the townfolk in “The Return From Bohemia” who peer over Wood’s shoulder as he paints and seem to be thinking “My nine-year-old could do better than that.” Through all the bucolic, sun-shocked farmscapes, through all the Norman Rockwell-esque images of people peeling fruit and milking cows, there is an undertow of emptiness, solitude, and loneliness. You can see echoes of Edward Hopper and hear echoes of Sherwood Anderson’s great novel Winesburg, Ohio.

In his 2005 biography of Wood, R. Tripp Evans finds an “indefinable dread” coursing through his subject’s life and work. Evans goes so far as to posit that Wood’s bulbous hills can be seen as male buttocks, and he sees something “ejaculatory” in those endless rows of corn sprouts. Well, maybe so, but there’s no denying that the picture on the cover of Evans’ biography was an inspired choice. It’s not the predictable “American Gothic.” It’s “Death on Ridge Road” from 1935, which shows a red truck topping a hill on a winding country back road, getting ready to barrel down toward an oncoming car that’s swerving, uncontrollably, toward a collision. Wood believe that art, like literature, must suggest a narrative, and there’s little doubt about how this story will play out. It’s my personal favorite in the show, which includes generous samplings of Wood’s eclectic output of jewelry, metalwork, murals, stained glass, book covers and illustrations, drawings, furniture, and whimsical confections made of springs, gears, wire, and bottle caps. Much like the recent Edvard Munch retrospective at the Met Breuer, this show makes the emphatic case that Wood was no one-hit wonder.

Maybe the reason this show spoke so deeply to me was because, without quite realizing it, I was ready to embrace its revision of the fable that Grant Wood was a champion of heartland wholesomeness—or that such a thing even exists. Last year I published a book called American Berserk, about my time as a cub reporter in a small central Pennsylvania town in the ’70s. “The place had a largely rural feel,” I wrote, “a small town surrounded by carpets of cornfields and orchards, livestock, and silos. Sometimes I would round a curve on a back road and have to stop the car because the landscape in front of me was so ridiculously gorgeous I could have sworn it had just finished posing for Grant Wood.” Three pages later I added a perception Wood might have appreciated: “I soon realized that through all this stay-at-home, God-fearing, heartland decency, there ran a streak of untamable bull-goose lunacy.” That lunacy led to some of the more spectacular stories I covered for the local paper, tales of arson, kidnapping, rape, murder, incest, the paranormal. I also covered more prosaic staples of small-town life, such as school board meetings and Rotary Club luncheons and, yes, car crashes on winding back roads.

Unlike the daily newspaper, Wood’s art didn’t traffic in the lurid or sensational. His way was to work quietly, with guile and stealth. The dread may have been indefinable, but it is always there. Gertrude Stein, of all people, seems to have understood Wood’s response to this dread. After seeing “American Gothic,” she wrote, “We should fear Grant Wood. Every artist and every school of artists should be afraid of him, for his devastating satire.”