THE CURONIAN SPIT — A bus ride from the last town in the European Union—Nida, Lithuania—across the border into Russia’s Kaliningrad region took less than an hour. The morning sun warmed sandy dunes along the shore of the Baltic Sea. There was hardly any traffic, just a few tourists and mushroom pickers stalking wild fungi in the lush vegetation of a national park. The bus glided quietly under pine trees on the only road in the Curonian Spit, a narrow stretch of land that is divided between two nations and, perhaps more critically at this moment, between two armies.

The northern part of the 98-kilometer-long peninsula belongs to Lithuania and is defended by thousands of North Atlantic Treaty Organization forces, while the rest of the peninsula is Russian, and similarly militarized.

Since the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, Lithuanian and Russian residents on both sides of the border in this once peaceful corner of Europe have been witnesses to frequent shows of military force.

This month, both NATO and Russia flexed their muscles. Lithuania’s Flaming Thunder 2016 drills brought together more than 1,000 ground troops to fire artillery and mortars.

On the other side of the frontier, Russia was reinforcing, too, in preparation for September’s large-scale drills by coastal forces. Dwarfing the NATO contingent, at least in numbers, the Russian Baltic Fleet is equipped with at least 75 combat ships, dozens of jet fighters and assault helicopters. Last week, the fleet fired BM-21 Grad multiple rocket launchers.

Little Lithuania (population 2.9 million) has watched in horror as Russia’s form of hybrid warfare, using covert operations, local “insurgencies,” relentless propaganda, and threats of outright invasion, has torn Ukraine apart. But unlike Ukraine, Lithuania is a member of NATO, and Lithuanians are praying they’ll be protected under its wing.

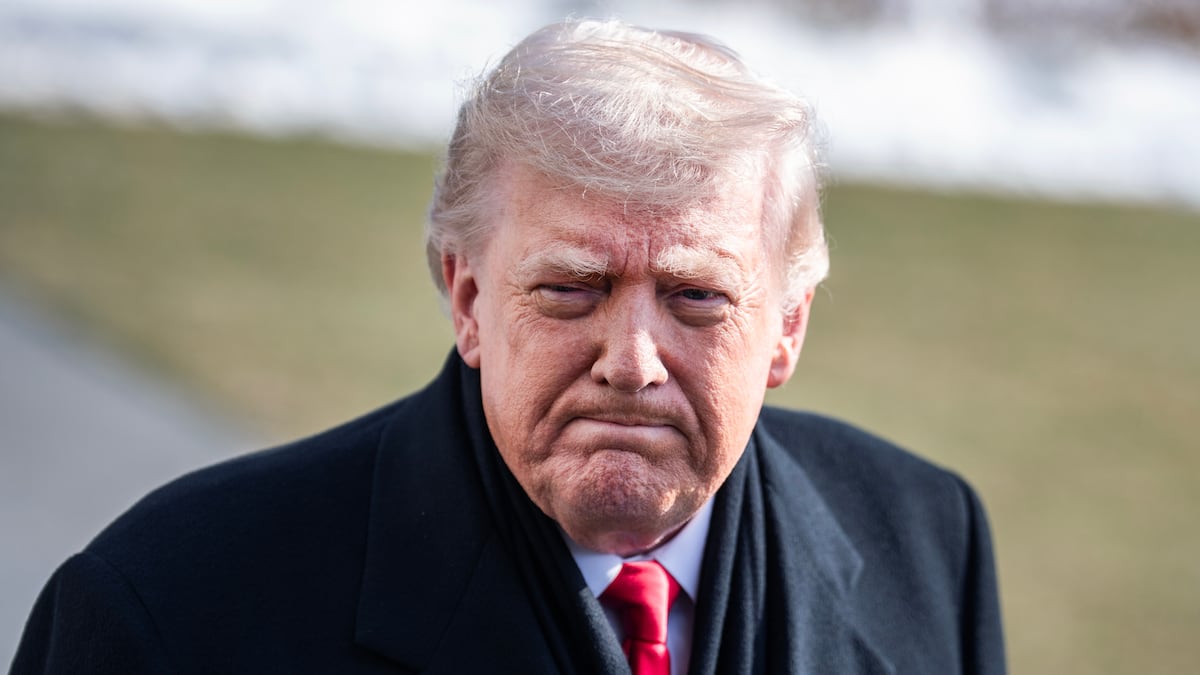

So last month, when U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump suggested he might not rush to the country’s defense unless he judged it had paid its NATO dues, a collective shiver ran through Lithuania. The evident coziness Trump feels for Russian President Vladimir Putin does not encourage confidence here either.

U.S. Vice President Joe Biden, on a visit to the Baltics last week, told his audience, “Don’t listen to that other fellow,” meaning the unnamed Trump. “He knows not of what he speaks.”

For the moment, the promise NATO has made to its three Baltic members—Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia—is a deployment of up to 4,000 troops in the region, clearly intended as a tripwire should the Russians make an overt move.

But that, in turn, is spun by Moscow as a provocation and perhaps even a threat to the Kaliningrad enclave: Russian territory that lies between Lithuania and Poland.

So, right now, relations between Moscow and Vilnius look very grim indeed. Lithuania’s foreign minister, Linas Linkevicius, refers to Russia as an “aggressor” using “old KGB methods.” On the ground, meanwhile, people view the return to Cold War rhetoric and war games as a potential disaster.

As we waited in line at Russian customs on the border, the bus passengers discussed the artillery drills Russian forces had started in Kaliningrad a couple of mornings before. A middle-aged Lithuanian woman, Agota Gaurdas, and her husband, Virgilijus Gaurdas, said they were “terribly tired of the increasing threats” causing militarization of the region around their home in city of Klaipeda.

“We hear airplanes over our heads and wonder whether it’s Russian pilots exercising to bring down NATO planes over our roof or it is our forces, which are now NATO, learning to shoot down Russian soldiers?” said Virgilijus, a civil engineer. “We are worried that one day, when they actually decide to fire at each other, there will be nothing left of Lithuania.”

Virgilijus said he did not believe that the Kremlin was serious about invading Lithuania, and blamed politicians for the Cold War games.

While the majority of Lithuanians prefer to live their lives as if nothing dangerous is happening, there are thousands who’ve mobilized into a partisan movement to defend their Baltic state.

Earlier this month about 50 volunteers from the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union had their own military exercises all over the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius. “It is counter-intelligence training,” said the drill’s coordinator, Haroldas Daublyus, a buff middle-aged man wearing a baseball cap. “Our mission was to identify Russian spies, who were hiding all around Vilnius; we trained to chase the spies, bugged their vehicles, and reported the group to authorities.”

The paramilitary Riflemen’s Union originally was established in 1919 when Lithuania declared independence and went to war against the Bolsheviks, the Western Russian Volunteer Army, and the Polish forces.

Soviet authorities banned the movement after they annexed Lithuania and the other Baltics in 1940. At the time it counted up to 50,000 volunteers, including famous writers, poets, and scientists.

In the past two decades, since the fall of the Soviet Union and the liberation of the Baltics, the movement has revived its partisan ideology. Today it claims up to 10,000 members, many of whom are current or former military.

Members of the Riflemen’s Union told The Daily Beast that they counted on Washington and NATO, but they also trained together with volunteers of similar partisan movement in Estonia and Latvia and felt ready to join the regular forces and defend their country’s 227-kilometer-long border at any moment.

“The idea that we should defend ourselves is common in a lot of people’s heads,” said Daubylus. “We are upset about what Trump says. He is betraying us all.”

“In the last two years we have tried everything from raids in the woods and shooting weapons to learning counter-intelligence tactics,” said Daubylus. “All of us, including 14-year-old members, are ready to unite with our neighbors and Ukraine and fight against the return of Russians.”

At the time Lithuanian partisans were catching Russian “spies” around Vilnius, the Collective Security Treaty Organization uniting six post-Soviet states also mobilized for major military drills in northwest Russia.

During the drills Aug. 16 to 18, Russian forces broadcast a woman’s voice repeating the following message to the supposed enemy: “NATO Soldiers! You are being brainwashed! This is not your territory that you fight on! Give up weapons, stop being puppets in your leaders’ hands!”

Last week the Lithuanian foreign ministry informed The Daily Beast that a majority of flights conducted by Russian aircraft in the international airspace near the Baltic States were not in compliance with international rules. Lithuanian authorities had to deal with “Russian transponders switched off, no pre-filed flight plans, [and] communication with flight control centers was not maintained.”

In Nida, once home to the German novelist Thomas Mann, residents depend on tourism and hope for peace for their business to flourish.

But in Kaliningrad there’s a certain excitement about the way Putin is pressuring the Baltic Fleet to get in shape. Ilya Stulov, who lives only 7 kilometers from the military base, knows exactly when Russian forces begin their thunderous drills, and hears through the grapevine how they’re doing.

“At least now Putin punishes commanders for missed targets during the drills,” says Stulov. “He sacked Vice Admiral Viktor Kravchuk and chief of staff Admiral Sergei Popov after the fleet missed at least one-third of their targets earlier this summer.”

All this serves Putin’s strategy of intimidation.

“The Kremlin makes us feel uncomfortable, threatens our security,” says Gintare Narkeviciute, the director for international affairs at the Ronald Reagan House, a think tank dedicated to promoting democracy and providing consultancy for Lithuanian state institutions. “They are not going to attack, this is psychological pressure.”

To young professionals in Baltic countries, who lived most of their lives identifying themselves as Europeans, the shadow of the Soviet past once again hanging over their heads is highly frustrating.

“We are worried that instead of peaceful reasonable development, Russia chooses to return to Brezhnev-style of militarization, of putting pressure and getting involved in our internal affairs,” Narkeviciute told The Daily Beast.

As a result of Russian counter-sanctions against goods from the West, Lithuanian exports to Russia have dropped by 39.2 percent, according to the foreign ministry in Vilnius. Farmers producing milk, cheese, and other products have suffered most, and have had to look for other markets.

To some older Lithuanians, whose youth was spent in the Soviet Union, especially to those who frequently travel to Russia for business or leisure, the idea of militarization and potential war with the neighbor simply sounds wild.

“If we do not listen to news about constant war games all around us, it all seems the same peaceful Baltics; but then we visit our friends in St. Petersburg and they tell us that EU propaganda turns us into zombies…,” my fellow passenger on the bus, Agota Virgilijus, told me, letting the words trail off.

She looked outside at families packing their car trunks with baskets full of mushrooms and added: “The sun, the dunes, and Baltic Sea are the same on both sides of the border of the Curonian Spit,” she said. “And so are the mushrooms.”