The plane banked and dipped for descent. I pressed my forehead against the tiny window, taking in the vast bay below, its surface broken by scattered islands. When Portuguese explorers first found shelter here in the early 1500s, they thought they’d hit the mouth of a great river—the River of January, Rio de Janeiro.

The name eventually settled on the city itself, which spreads along the bay’s west side. From the airplane, Rio was ethereal: a smear of white separating sky and water, anchored by great granite mountains blanketed with emerald green. There were no noises, no smells, no people, just water and mountains, possibility and light.

As the abstract elements below arranged themselves into familiar forms—beaches and buildings, highways, the crosshatch of tiny shacks seen from above, then the international airport on the largest of the islands—I felt the pull of this postcard city, with its palm trees and white sands, its languid heat. For years I’d kept this image in mind, retreating to it when I felt drained, cold, out of place.

Once I stepped out of the airport’s air-conditioned recesses and pulled onto the highway, the real Rio pressed in, an immediate assault on the senses.

To the left there was Guanabara Bay. Dense vegetation crowded the water’s edge and curled over it. The debris disgorged by this metropolis of 13 million people wreathed the shore: old couches, a bashed-in television set, unrecognizable plastic bits snarled in decaying plastic bags. I rolled down the window and the cloying scent of sewage filled the car.

A vast patchwork of favelas stretched out on the right. Boxy houses of unfinished red brick, stacked like kids’ building blocks, bristled with exposed rebar and hugged the highway’s shoulder. High acrylic barriers rose on both shoulders of the expressway. Their decorated panels replaced a view of the favela with enticing previews of the best Rio had to offer: samba musicians playing tambourines, children flying kites, the graceful outline of the Sugarloaf Mountain. Some of the acrylic panes were pocked with bullet holes.

Many of those exiting the airport locked their doors and rolled up their windows at this point, heeding those travel guide warnings that started with “To reduce your chances of becoming a victim … ” and then settled into the safety of their air-conditioned cocoon, thoughts speeding ahead to their own picture postcards, the places they came to see: Copacabana, Ipanema, Lapa, Leblon, their very names rhythmic and evocative of summer, sunshine, and good times.

But leaving the airport that day I wanted all of Rio, its hot, humid breath, its extremes. I was home. I rolled the words around in my mind, trying them out: Rio, home.

I settled into a hotel in Ipanema, a few blocks from the ocean. This was the Rio most foreigners came looking for: upscale but still casual, its streets lively with eateries that spilled onto the sidewalks. Just down the street was the corner bar where, back in 1963, a poet and a composer talked music, nursed their whiskeys and watched for a local girl who made the sun shine a little brighter when she walked by, “tall and tan and young and lovely,” on her way to the sea. The pair, musician Tom Jobim and poet Vinícius de Moraes, would cull the intimate sound of bossa nova from those long, sultry afternoons, and distill that quintessential Rio tune, “The Girl from Ipanema,” from the deceptive simplicity of the young woman’s gait.

Ipanema still had this easy charm, this ability to catch the eye. No matter that buses now stopped and huffed their air brakes by the open-air bar where musicians once scrawled lyrics on the back of napkins, or that troupes of young, shirtless men now played a few rushed chords and did capoeira backflips during traffic stops, hoping for some tourist change. Ipanema still had that levity, like the girl whose glance once filled the world—or at least one grimy corner bar—with grace.

I’d arrived in November, almost at the beginning of the South American summer. On Sundays, the beachfront road was closed to cars and thronged with people. I dropped my bags at my hotel and pushed through palm-draped lanes packed with kids on bikes, skateboarders, couples, bodybuilders, grandmothers with their broad-brimmed hats, a river of bodies tangling and touching in the golden light. Rio’s denizens, the Cariocas, feel at home in a crowd and don’t mind brushing past strangers. This comfort with closeness left a thin film of other people’s sweat on my bare arms and shoulders.

Ipanema is slender, narrow at the waist, with only seven blocks separating the Atlantic to the south from a lagoon, the Lagoa, to the north. Forested mountains rise behind the lagoon’s dark mirror and hold aloft the white stone statue of Christ the Redeemer—just Cristo to the informal Cariocas.

In this gorgeous little strip of land, burdened as it is with ungainly buildings, the frenetic hum of the city slows down. I felt it as soon as I stepped out of the hotel. It is hard to take anything too seriously when locals flip-flop around in Havaianas, board shorts, and post-beach dresses over still-damp bikinis, the flimsy fabric slipping off bronzed shoulders just so.

From the edge of the sidewalk I surveyed the beach. To my right, the sand ended at the granite flanks of massive rock outcroppings. On that hillside, perched above the ocean, was the Vidigal favela. Two massive boulders jutted out behind it: the Dois Irmãos peaks, the name meaning Two Brothers for their closeness. To the left was Arpoador, a park of immense granite formations that tumbled into the ocean and where Cariocas liked to gather for a sunset beer. The name harked back to a time when whales were harpooned off this coast. Now fishermen cast their lines from the base of the rock and surfers swarmed the break at its feet like sharks.

Vendors in numbered shacks, or barracas, claimed the space between the sidewalk and the water. Burnished by decades in the sun, these men kept a close eye on their realm, offering prospective customers a sun umbrella or beach chairs, ice-cold water or a beer. In time, I’d pick a favorite spot on the beach, get to know them by name, and be recognized by them in turn.

I bought a fresh coconut, which the barraqueiro, the vendor, fished out from a Styrofoam cooler and hacked open with three expert chops of the machete. The agua de côco inside was sweet and cool, the perfect balance to the heat of the day and the tang of sweat and sea spray. I sat on one of the concrete benches facing the sea and reveled in it: coconut, sun, ocean breeze.

This was the Rio I’d dreamed of for years, and there was a deep satisfaction in feeling the present layer comfortably over my matching memories. Volleyball players rose and curved their bodies into perfect arcs above the net, supple in the honeyed light. Down near the water, gaggles of girls lay facedown on their sarongs, side by side, rows of perfect bums to the sky. Hawkers slung with ice chests, coolers, grills, and other paraphernalia trudged by calling out their wares: peanuts, sodas, beer, caipirinhas, fresh shrimp, grilled cheese.

Never mind that my legs had the indoor pallor of white asparagus and I was alone, disconnected from the clumps of Cariocas, a stranger to the vendors. I was home. Perhaps it would be this easy. Perhaps all it took was repeating it a few times, like a prayer or a spell, and it would start to feel that way.

Rio de Janeiro had always been a port of entry into Brazil, a place of connections, deals, and trade. Ships coming from Africa disgorged onto its dock the enslaved men and women who’d wrench the country’s fortune from its plantations and mines. When the Portuguese royal family fled from Lisbon in 1822, just ahead of Napoleon’s invading army, they’d sailed to Rio and made it the seat of their empire.

For my family, too, Rio was a threshold. My parents were born in Minas Gerais, a Texas-sized state of coffee and cattle, rolling hills and baroque churches. Rio was their gateway to the world beyond; it was where they started their married life, staying just long enough for my mother to have three children and for my father to start working for the Brazilian oil company, Petrobras.

It was from Rio that we left for Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in 1977. When he waged war against Iran in 1980, we hid under the stairway to escape the air raids that shattered windows along our dirt street in Basra. My father had to stay behind to close up the office, but my mother crammed her three children onto a school bus and, along with other Petrobras families, headed toward Kuwait. Bombs rained down on oil rigs along the way, turning them into furious towers of fire whose roar could be heard for miles.

We took only what we could carry—a change of clothes and food for the unknown road ahead. Along the way we had to stop. I didn’t know why, or where we were. The road shimmied under the sun, a long asphalt ribbon that unspooled over the desert, equally forbidding in either direction. We sat on the dirt ground under a white-hot sky for what seemed like hours, surrounded by other dazed evacuees. Iraqi and foreign, we were all trying to escape the war. Unlike us, many of the local families were walking. There were children, goats, sheep, all equally round-eyed with fear. A hand snuck into the bag that held our food for the trip, making off with the hard-boiled eggs. My mother shrugged it off: “They need it more than we do.”

In Kuwait, a five-star hotel allowed us and other Brazilian families to sleep on pool mats scattered around their ballroom. Eventually, we found our way from that Kuwaiti ballroom to my grandmother’s house in Minas Gerais. For months we waited for my father and hung on to the news for reports of the war. As soon as he rejoined us we were on the move again, this time to Malta, a dot in the Mediterranean. A year later we moved again to Libya, where national television featured the public hanging of political dissidents, and the square-jawed profile of a young Muammar Gadhafi loomed on massive outdoor billboards and in nearly every home.

After years of flirting with Brazil, we moved back in 1984. I’d wanted to go back; still, the landing was rough. I was excruciatingly shy. Attending an international school run by oil companies in Tripoli had not prepared me for junior high in Rio de Janeiro.

My private school classmates had all been raised in the city’s new gated communities. They’d been honing their tastes for years, and even their pencil cases had brands. I was all wrong: kinky curls that my mother treated like topiary, trimming into a perfect circumference; glasses in pink, shatterproof plastic so they’d last the year, and then, oh yes, a retainer. My sneakers, from the government-run store that carried Tripoli’s few consumer goods, had no brand at all. They were green, the color of Libya’s flag, with orange trim. On their sides, where other kids’ shoes said Reebok, mine had the country’s official name: “Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriyah.”

But I was finally in Rio and curious about this place where everyone spoke the Portuguese we used only at home, and where I was supposed to—finally—belong. I threw myself into it the way I knew how: reading. After school I would grab the newspaper, spread it over my bed, and try to make sense of the turmoil wracking the country.

After two decades under a military regime that had seized power in a 1964 coup, Brazil was transitioning to democracy. The first civilian president, chosen by an electoral college, faced emergency surgery the day before taking office and died of septicemia. The vice president was inaugurated in his stead, but what should have been a moment of celebration was tense and uncertain, weighed down by national mourning.

I’d watched the funeral from my grandmother’s house, with cousins, aunts, and uncles all clinging to the television. My grandmother broke into tears. It all seemed so frail, this transition, the new government. Everything was shifting at once—political allegiances, business connections, power relations, even the amount of nudity on newly uncensored television.

Disastrous economic policies crashed one recovery plan into another. Brazil would have six currencies between 1986 and 1994. With each new set of bills, the government slashed zeroes from numbers that inflation had made so large they no longer fit on printed money. Prices went up so fast that shoppers tried to snatch up the day’s groceries ahead of the supermarket employee with the mark-up gun, grabbing soap or a bunch of bananas before he had a chance to put on the new price tag.

Even to my young eyes, the country was an unmoored disaster. The city of Rio was no better.

Rio de Janeiro had once been the seat of empire, and after independence from Portugal, it became the capital of Brazil. It lost that status to Brasília in 1960, along with federal jobs and money. As the country’s economy slipped into years of instability and hyperinflation in the ’80s, the city’s decadence continued. Genteel neighborhoods fell apart. Squatters took over abandoned warehouses on Avenida Brasil. The once-grand shipyards disintegrated in the salty ocean air. Giant cranes, visible from the highway that looped around the port, held up their heavy heads for years like the last survivors of an ancient race, then crumpled as rust ate at their joints. Downtown, entire buildings went vacant, their rows of darkened windows reflecting the hopelessness of the moment.

The economic disarray and escalating violence squeezed the population. Business executives were targeted for kidnappings. The rest of us worried about carjackings and holdups. My brother came home wearing only shorts one day, robbed of his T‑shirt and sneakers by kids not much older than himself. Women covered their car windows with dark film so as not to look like easy targets, and no one stopped at streetlights after dark. Those who could afford it retreated behind barred windows, into gated communities and bulletproof cars. Many left the city or the country altogether.

My family had settled in one of the gated condomínios then sprouting in the sparsely populated west. Barra da Tijuca was gorgeous—a long strip of marshy flatland hemmed in by green mountains to the north and miles of white sand and the Atlantic to the south. Rivers streamed from the heights and collected in lakes and lagoons. The new condomínios, watched over by an army of uniformed doormen and private security guards, filled up as fast as they were built. I lived in one of these new communities, called Nova Ipanema, and went to school in another, Novo Leblon, names that suggested new versions of the old Rio neighborhoods and promised a life that could no longer be found there.

Far from the heart of Rio, I sought out that city as I could—in occasional visits, and always, through the news. I read about the favelas that clung to steep, unstable hillsides, and the hard rains that inevitably sent dozens of their homes tumbling down into the mud.

By the ’80s, drug lords had taken over these shantytowns, turning them into fortresses nearly impenetrable to police. This new power was put on spectacular display when Escadinha, a drug kingpin with Robin Hood pretensions, was hoisted out of his maximum-security prison by fellow gang members in a helicopter. The cinematic escape was all over TV. He gave interviews, boasting about the help he offered the favela that harbored him and his gang, the Comando Vermelho, or Red Command.

Turf wars between gangs or with the police meant shoot-outs. The press at the time coined a phrase, bala perdida, or lost bullet. The unintended victims of these stray shots often made headlines: the young mother killed while sitting at home with her two year old on her lap, the kid with a book bag caught by a bullet on his way down the hill, his bloody public school uniform displayed in the nightly news.

This Rio I read about in the newspapers brushed up against me on occasion, in spite of my sheltered condomínio life. Once, it left an indelible impression. It happened in 1989, while I was walking on Ipanema beach on a Sunday afternoon. I felt a jab in my side. Turning, I looked right into the jaundiced eyes of a drugged-up kid, no more than nine or ten years old, his nose crusty with snot. Gaggles of these children roamed the streets back then, sleeping in doorways and under overpasses. This was before crack hit Rio. They’d huff shoemakers’ glue for a cheap high. Sometimes you’d catch the chemical smell on their breath.

This kid held a jagged piece of a beer bottle against my side, mugging me for whatever I had in my pockets. He stood close, mumbling his words.

“Tia. Trocado, pra comer.” Change, for food, he said, half begging in spite of the sharp glass pricking the soft flesh beneath my ribs.

I was only 14, but he was calling me tia, aunt. This is a very Brazilian expression, part affection and part respect, that kids use when talking to the grown-up women in their lives—their teachers at school, their friends’ parents. I was a child being threatened by a child. It was heartbreaking and revolting.

A few months later, in August 1989, we left Brazil again for my father’s next assignment: Houston. I went back to a sporadic relationship with Rio. The image of that kid stayed with me as a reminder of what the city had become—something broken, abandoned, its decay more tragic because of its promise, like fruit that’s picked too green and rots before it ripens.

More than two decades later, I was back. The country’s prospects had changed, and the city was shaking off the torpor of decades. But the clock was ticking. Rio had less than four years to go until it hosted the World Cup, and six years until the Olympics. The challenges were clear from the moment I landed in Rio’s old airport, with its perennially broken elevator, and drove past the polluted bay and the favelas alongside the highway. A massive overhaul of long-neglected infrastructure was in order; stadiums needed to be refurbished, new Olympic venues built from scratch.

The biggest challenge, though, was security. Rio’s Olympic bid had promised “a safe and agreeable environment for the Games,” but this would not be easy. Gangs like the Red Command, which I remembered from my time in Rio a generation ago, had taken over favelas the size of small towns, marking their territory with graffiti tags scrawled on walls. From these safe havens they targeted the neighborhoods below. The police were poorly trained and ill-equipped at best, corrupt and lethal otherwise. Disputes between them, or turf wars between gangs, meant shoot-outs with a high body count.

Rio would have to confront all this under the scrutiny of national and foreign media, which had the city in its crosshairs. In this era of social media and Internet activism, Brazil’s international standing would be measured in quantifiable terms such as gross domestic product, but also in the buzzwords that were becoming the yardstick of a country’s status in the twenty-first century: human rights, equality, justice, environmental sustainability, and quality of life.

As I unpacked that Sunday night, getting ready for my first week of work, I wondered what lay ahead for me, for Rio, and for Brazil.

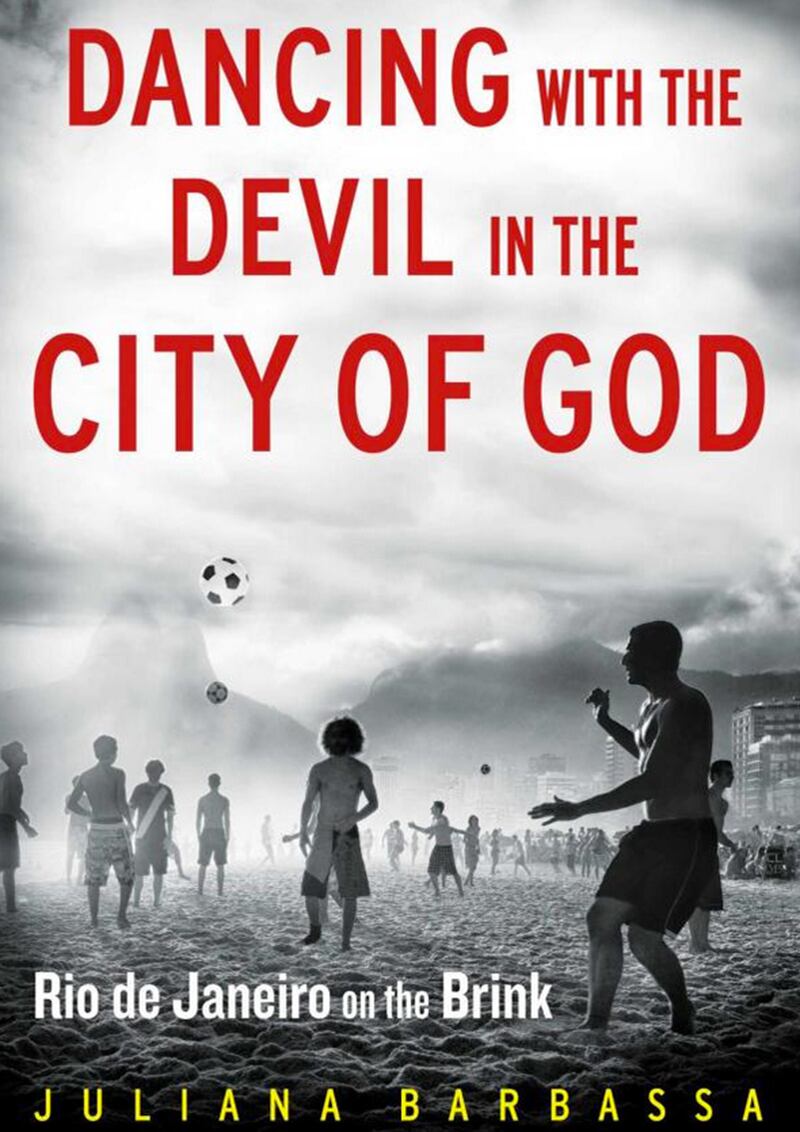

Excerpted from DANCING WITH THE DEVIL IN THE CITY OF GOD: RIO DE JANEIRO ON THE BRINK by Juliana Barbassa. Copyright © 2015 by Juliana Barbassa. Preprinted with permission from Touchstone, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Juliana Barbassa was born in Brazil, but she had a nomadic life between her home country and Iraq, Malta, Libya, Spain, and France before settling in the United States. Barbassa began her career with the Dallas Observer, where she won a Katie Journalism Award in 1999. She joined the Associated Press in 2003, and after receiving two more awards from the National Association of Hispanic Journalists and the APME, she returned to Brazil in 2010 as the AP’s Rio de Janeiro correspondent. Dancing with the Devil in the City of God is her first book. For more information, visit: julianabarbassa.com.