“G isn’t for Gucci, but for guerra,” the Italian newspaper La Repubblica once reported. Guerra means war in Italian.

In House of Gucci, her chronicle of the epic family saga, Sara Gay Forden agrees with the comparison, describing the dynastic Gucci conflict as one of “shifting alliances, sudden betrayals, and rapprochements widely characterized in the press as a ‘Dallas on the Arno,’ but actually more reminiscent of the entrance of Nicolo Machiavelli’s renaissance Florence.”

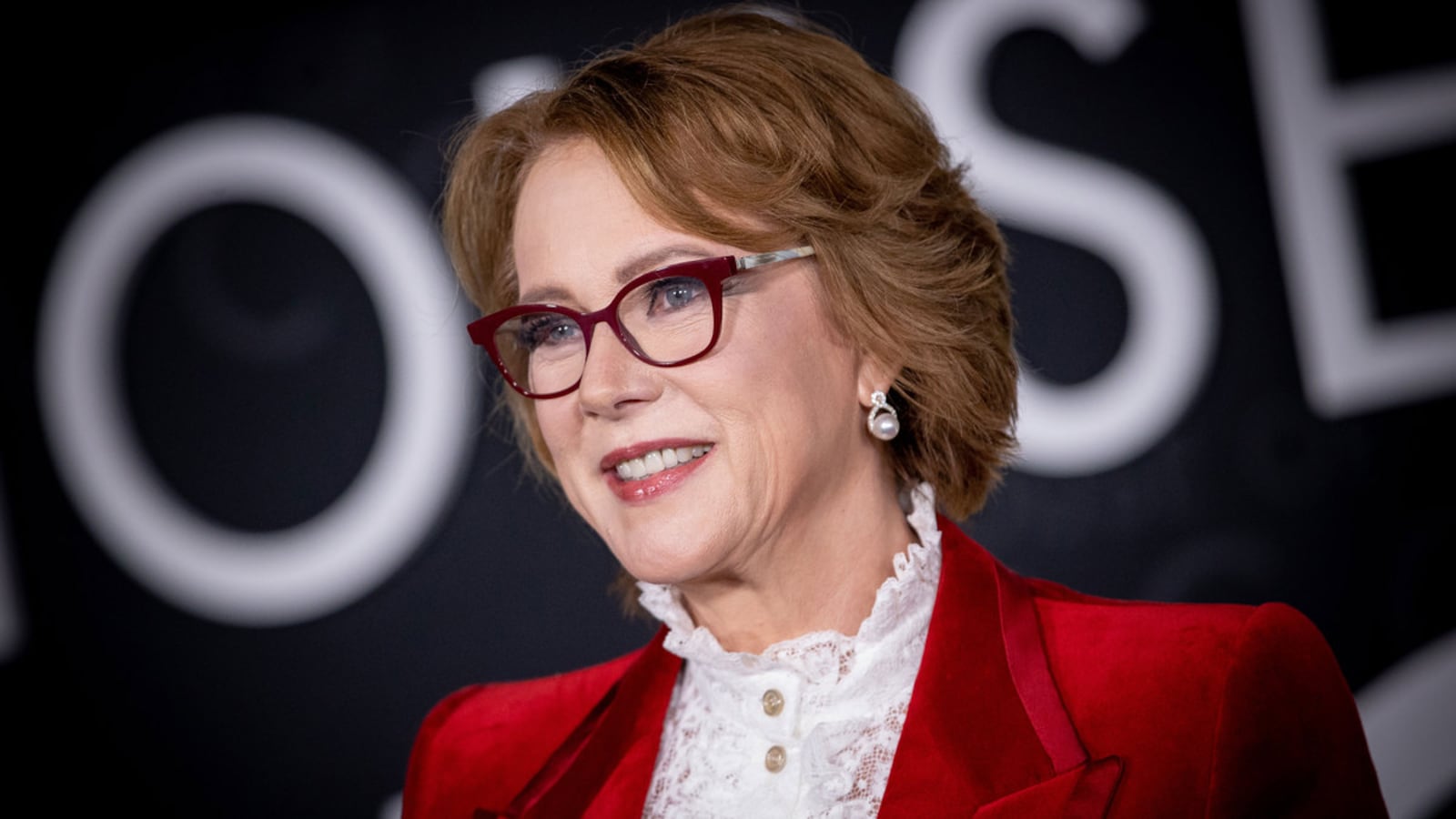

Deeply versed in Italian family-owned luxury labels—she was bureau chief and business reporter for Women’s Wear Daily in Milan from 1993-1999—Forden conducted hundreds of interviews to encapsulate multiple generations of the Gucci family: the egos and greed, as well as the heritage and pop cultural allure. She noted how the company expanded internationally to Rome, New York City, Paris, London, and Palm Beach by 1972, with a why-wait-for-customers-to-come-to-us attitude; how much celebrity endorsement from movie stars and political power players mattered—and early at that, with Ingrid Bergman carrying a Gucci bamboo-handle bag and umbrella in a 1953 Rossellini film; how tempestuous the family was, with rages à la Scott Rudin (Forden describes them as “alternately ecstatic and furious”); and how rampant counterfeiting included the manufacture of Gucci toilet paper and an entirely fake Gucci boutique in Mexico City.

Amidst all this, the murder of ex-CEO Maurizio Gucci lies at the center of this tumultuous history.; the trial thereafter became “the Italian equivalent of the O.J. Simpson case in the United States.” This provided the basis for Ridley Scott's big-screen film—set for release Nov. 24 and starring Lady Gaga, Adam Driver, Jared Leto, Jeremy Irons, and Al Pacino—which has produced polarized reactions from critics.

The label has endured it all, celebrating its 100th anniversary this month with a splashy display in Los Angeles. The Daily Beast spoke with Forden via Zoom to discuss unreliable narrators, Lady Gaga as Patrizia Reggiani, and how fashion industry drama now pales beside big tech.

Regarding the germination of this book, how did you decide this was an idea to pursue?

I had always wanted to write a book—but I’m a journalist, not a novelist, and I was not really sure what I would write about. As the Gucci story started to build, I was writing frequent stories for Women’s Wear Daily, and really delving into everything that was going on in the family: the history of the company, the struggles that Maurizio was having with the relaunch. This was in ’97. I realized that there was a narrative: one that had a rise and fall and a rise again.

What was your trajectory as a journalist—how did you end up in Milan?

I never set out to cover fashion. My dream was to be a foreign correspondent and to write about business, about the people behind businesses. I had started out as a local reporter in the D.C. area, then went to Johns Hopkins for grad school—I did a master’s in Economics and International Affairs—and they have a school in Bologna. That’s how I got to Italy. I learned Italian and I loved it. I decided I wanted to work as a business journalist in Italy. In Rome, the story was more about the Vatican and politics; Milan was a financial center, a plum spot for foreign correspondents. There was the formation of the EU, so a lot of cross-border deals.

I realized that the big upcoming story in Milan was the fashion business and family labels. Names like Krizia, Missoni, Armani, Versace, and Prada started coming up. And in the span of a few years, these family businesses were exploding into mega brands. It was in that context that I started writing about Gucci, though they were not a leader in the fashion pack by any stretch. They were kind of considered an outsider. They were from Florence, they were a leather goods/accessories company that didn't have ready-to-wear. It was really only after Maurizio decided to relaunch and brought over Dawn Mello—who had been the president of Bergdorf Goodman—that the fashion world started to kind of take notice of Gucci. I mean, Gucci had been a hit in the ’60s and ’70s, but in the late ’90s, they were just kind of starting to crawl back onto the fashion map.

The scope of people you spoke with is huge. How did you decide on those parameters?

That was really a matter of feeling my way along. I did a proposal before selling the book—I did a very detailed outline as part of that. I knew I wanted to start with Maurizio, because he was the connection between Gucci’s past and its future. He was the person who compelled me to write the book because I felt that he was going to be forgotten. The people who came after him and actually turned the company around were obviously having huge success. I mean, he was a terrible businessman. He was creative, he was excited about his plan. And he ultimately brought the company to the brink of bankruptcy. But his vision was correct. And the people he brought in were very talented. Tom Ford was hired by Maurizio. So I felt it was important to cement what he had been able to accomplish.

And then there were pieces of the story that just took off completely unexpectedly while I was writing the book. The main one was the takeover battle between Bernard Arnault and François Pinault. That happened quickly—I had taken a week vacation, I was at the beach, and one morning I opened up [Italian financial newspaper] Il Sole 24 Ore. And I see that Arnault had bought a 5 percent stake in Gucci. And I was like, Oh my God, here we go. That was happening while I was trying to research the history.

Then, within the fall of ’98, the trial started. That was a three-month trial, and I was in court almost every day for those proceedings. I felt that I needed to be in the courtroom so that I could really get the flavor of what was going on and pick the most relevant moments to write about. The reporting was time-consuming, because everybody had such a different point of view about what happened that I spent a lot of time trying to rationalize everybody’s perspective. Because I figured I can’t just tell one side of the story. If I balance it out, then the truth is going to be somewhere there in the middle.

It sounds like a diplomatic nightmare having to honor these different takes, where each interpretation is considered monumentally different based on who you talk to.

That was a big challenge for me in writing the book. There was a book written in the ’80s by a British journalist, Gerald McKnight, which is based primarily on interviews with Paolo. People said lots of things were inaccurate about that book; I realized the importance of trying to balance out the opinion of the person that I was interviewing. I did a lot of interviews where I was retreading the same information over and over again. But every time there would be, like, one nugget of something new—a detail or perspective that I hadn’t gotten. So I would just pick that up and take it home. That was how I fleshed out the story.

There are already some Gucci heirs who are dismissing the movie’s portrayal of the family. How essential was the family approval? Were there some who didn’t want to talk to you, or made life difficult relative to this project?

Well, first of all, I want to say I really respect the feelings and experiences of the family members. This has been a family tragedy. So I think we have to acknowledge that. But my emphasis in telling the story was really to show how the family created this incredible brand that just keeps going higher and higher. One of my challenges when I was writing the book was that many of the protagonists are no longer alive. Patrizia Reggiani was in jail, and the prison authorities wouldn’t let me interview her. I spoke a lot with Roberto Gucci, reconstructing the family history and dynamic. He acknowledged that the loss of the company was like a dagger. It was very painful for them, and then the murder of Maurizio… even though they were angry with him, obviously that was a tragedy.

I did try to speak to Patrizia Gucci, who was Paolo’s daughter. She wanted to be paid for an interview. I wasn’t paying for interviews; I explained that, and she decided not to engage. I think she could have had an opportunity to really share her father’s story; he was one of the most colorful, intriguing characters.

Then there was Domenico del Sol, who had the longest arc of anyone in the whole story, because he started right at the beginning of the family battles. He was at all the board meetings, he saw what happened, he knew the issues. He really dedicated himself to this company. In the end, he became the CEO and was the one who led Gucci into a new era as a multi-brand, top-of-the-line fashion company.

There were a lot of people who worked for Gucci for many years, who were very loyal, who knew the whole story. People in the factory in Florence, in the shops in Florence and Rome and Milan, who knew the Guccis well. I got a lot of help from them.

That makes sense. Their insight into the day-to-day is just as necessary.

Yes. There was a network there—the yarn-makers, the cloth-weavers, the leather-workers—it was a whole world that was supporting this vision of quality and luxury and style. Now fashion is taking a different turn—it has become a global sourcing system rather than just Italian, because of the rise of manufacturing in China and Asia and North Africa and Eastern Europe. It has dissipated. It used to be a more in-house process.

What was the timeline of writing the book?

I started writing in 1998; I took a two-year leave of absence. It took me 18 months to research and write and cover the trial. For six months, I was copyediting and refining; I had to cut 100 pages out. I just, like, squeezed every single sentence and got it to be as lean and as clear as I could. The hardcover was published in 2000, the paperback in 2001. My publisher asked me to write an epilogue for that. I did, and there was still a lot going on with the company.

And now fast-forward 20 years, they asked me to write an afterword updating the highlights. I start with Patrizia: she’s coming to the end of her sentence, she’s getting passes for good behavior. It’s an account of her being seen now: in the social circuit, in the shopping area of Milan. Then I go through the whole period of Tom Ford and Domenico del Sol, who left the company. I interviewed Pinault. That was fascinating to me: How did he think he had achieved the renaissance of this historic label? This decision to put Alessandro Michele at the helm of Gucci was incredible. He’s touched a nerve and it’s been incredibly successful. I don’t know if you saw the fashion show [on Nov. 2], it was streamed live in L.A.; it was their centennial blowout. I mean, they shut down Hollywood Boulevard. Everybody in the world was there. It’s the hugest fashion show I’ve ever seen in 15 to 20 years of covering the industry.

Let’s talk about the movie—what kind of discussion did you have with people involved?

I collaborated on the screenplay. Roberto Bentivegna is a talented young Italian writer. I felt like he really was probing the twists and turns of the story and trying to understand the characters and their motivations. It's a different language writing for a movie versus writing a book. I'm super excited that a labor of love that I, you know, sweat and cried and bled over 20 years ago is now going to be seen by a much bigger audience.

Did you feel the casting choices were evocative?

Yes, extraordinarily. Lady Gaga is incredible and has many similarities with Patrizia—like, she’s very petite, she’s sexy, she’s stylish, she’s got verve. Adam Driver’s a phenomenal actor. Al Pacino is one of my favorites. And a director like Ridley Scott really knows how to tell an epic story.

But what about this decision to do the Italian accent in English? That seems ripe for caricature.

I've talked to several Italians about that. I mean, I love their accents. Especially I like Paolo’s. There's a little scene from the trailer where Paolo talks about his outfit: It’s chic-uh! It’s perfect.

We’re talking Jared Leto?

That’s Jared Leto. There’s another scene from the first trailer, where Patrizia has the cigarette in her mouth, and she goes, Brah-vo! I was like, Oh, my gosh, it’s just so real. So the work that they did to develop those characters was clearly successful. Oh, and I was telling you, I talked to several Italians who said they really liked the accent. I mean, I know there’s been more debate about that in the Twittersphere. But I guess you’ll have to see the movie.

It’s one of those things that could really upset a suspension of disbelief, if someone’s not credible. I was wondering if you’ve seen the Ryan Murphy production about the Versace saga?

I didn’t watch the Murphy story, because I lived through that. That was also so shocking and so sad that I didn’t feel like I needed to watch it again. When I was reporting on the Italian fashion industry at that time, it was just all around us.

Fashion might have been more niche in the ’90s but is now decidedly not niche: It bleeds into other forms of pop culture. Maybe because the platforms through which you can experience it are different now. Is there an increasing thirst for fashion history as a kind of juicy soap opera?

Everything is different. What was fascinating about covering this industry was how these fashion houses were geniuses at keeping a finger on the pulse of what was new and cool and hip. They knew all the latest music, the movies; they knew the references, because their job was to sell us things that we don't need, right? Like, we’ve all got plenty of clothes and handbags in our closets, but they had to somehow make us enamored with the thing that they were doing. And so they use pop culture to sell us. Because we had to have the latest thing. And yet they somehow were able, I think, to put more meaning behind it.

But now, the role of fast fashion… the whole advent of social media, and people putting their own stories out there, and making their own style completely exploded. It used to be much more of a closed world. As a reporter, as a journalist, you were never supposed to be part of the story. Like, we didn’t do selfies, you know? But now, that’s all people want to know, like, how did it feel to be doing this or that?

And even now, like this Gucci show, everybody could watch it! Whereas traditionally, the fashion show was a trade event, the buyers went because they needed to see that work, get the interpretation of the design for how to show these clothes, so they could place their orders and get the clothes into their stores. It was a technical working appointment. It wasn’t a social engagement, although it was also very social. But I was really happy to be able to be watching the [Hollywood Boulevard fashion] show from the comfort of my home.

One thing that knocked me sideways was the prescience of this older generation. Rodolfo was pioneering in filming his wedding in 1944 and filming the Beverly Hills Gucci boutique opening in 1968. I was like: This guy is a social media pioneer! The idea of documenting both himself and the brand—it’s not new, actually. And you’ve got Aldo, who’s realizing globalization is the best way for a brand to thrive. That also was very prescient.

The sense of marketing—I mean, he was a marketer, right? I didn’t think about it that way, but you’re absolutely right. He was trying to create a living document that he could leave to his son, to leave a trace of where he came from. This older generation, the way they create structures is actually totally consistent with how we do things now—even if obviously the scale, there’s no comparing. But a lot of how you get a brand out there and connect yourself to it… these basically have already been reflexes for half a century, which the story of Gucci proves.

You’re not covering fashion anymore—you’re covering tech. Do you feel like there are parallels across these two industries?

I’m an editor with Bloomberg in Washington, D.C. I moved back to the States from Italy in 2010. My team looks into what the biggest companies are trying to get done in Washington. We cover the White House, Congress, the agencies. How are they positioning themselves? The connective tissue is the stuff that happens behind the scenes. Now we’re in a situation where we have two federal lawsuits filed: one against Google and one against Facebook, with investigations that are growing. And we have Congress trying to wrestle with these questions about dominance, privacy, consumer welfare. There’s some parallel in the sense that what we wear and how we present ourselves is very connected to who we are. Tech companies have become absolutely intrinsic to how we live. Big tech platforms have more power than the fashion brands do, though, so it’s an outsized comparison. I’m fascinated by how these companies intersect with our lives, and by the power that they’ve acquired. In a way, I swapped Armani/Gucci/Prada for Google/Amazon/Facebook.