A vengeful bully who plays by nobody’s rules but his own has taken over the town. He is supported by a band of hired thugs and cheered on by a large and vocal minority of the community who nurse a set of grievances against the established order. Meanwhile, the majority of citizens are anxious and deeply divided over how to withstand the despot and his mob.

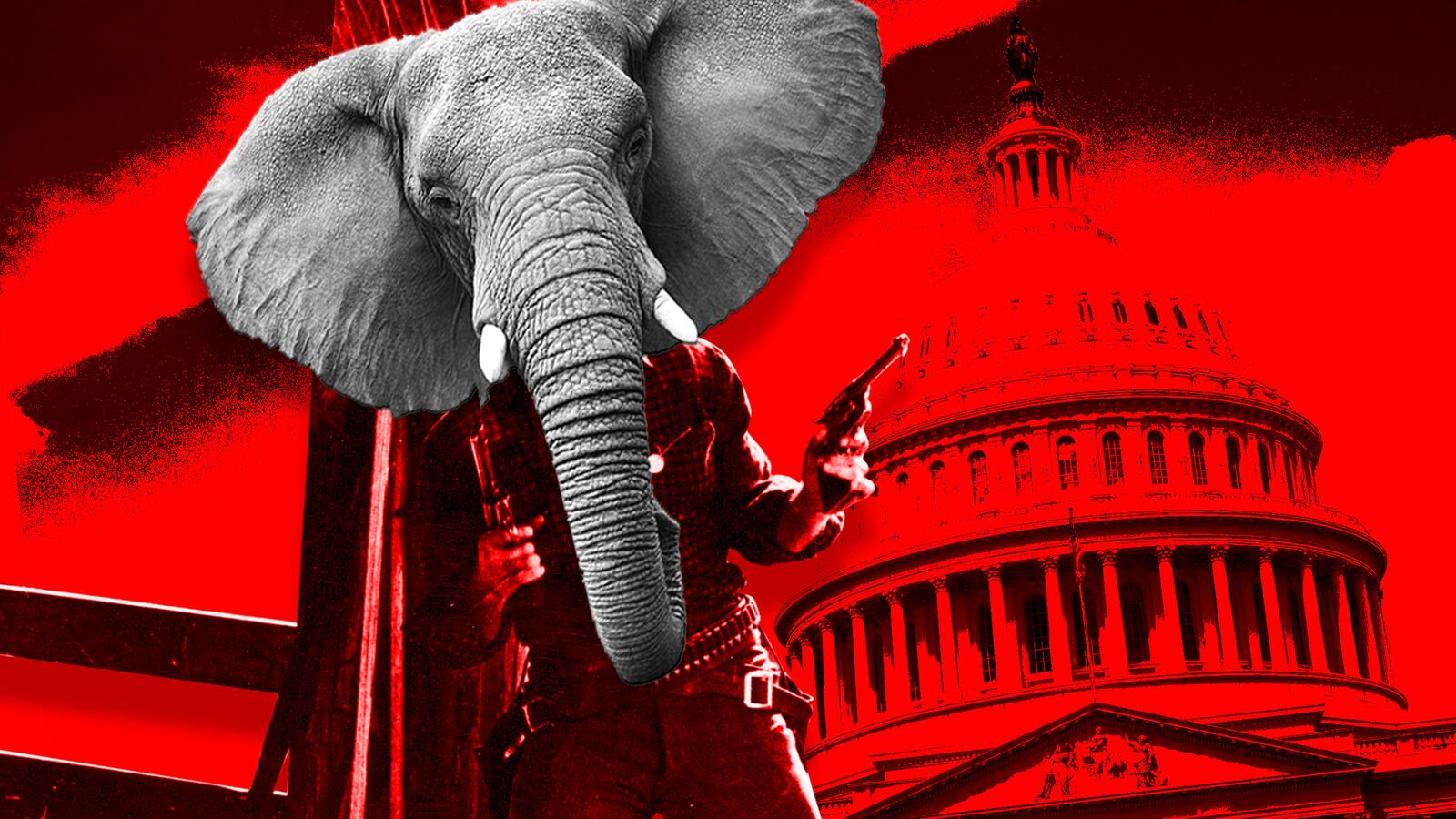

It’s not an exact analogy, but I can’t help thinking about High Noon, the classic 1952 Western starring Gary Cooper and Grace Kelly, as America gets used to life under Donald Trump. I’ve spent the last three years researching and writing a book about the movie and the turbulent political era that helped inspire it. And I’ve come to realize that the plot, characters, and context all reflect our own troubled age.

High Noon was created in another time of high anxiety and pitiless personal politics: the blacklist era. The spirit of national unity and international cooperation after the triumph of World War II had given way to the Cold War with the Soviet Union, a brutal conflict on the Korean peninsula, and a nuclear arms race that would last half a century. The progressive coalition forged by Franklin Roosevelt that had ruled the country for a generation was under siege from a coalition of traditional conservatives, embattled working-class populists who felt excluded from their fair share of prosperity, and self-styled Americanists who believed outsiders were plotting to subvert our culture and our values. Together, they constituted a classic backlash movement against the usurpers—liberals, Jews, and Communists in those days; gays, Muslims, and undocumented immigrants today—who had stolen our country. The self-appointed guardians of American values were determined to claw it back—and Make America Great Again.

For many Americans, Communism posed an existential threat even more frightening than that posed by Islamic extremists today. Communists, after all, could be anyone—neighbors, relatives, close friends. They looked and sounded exactly like us, yet they were agents who marched zombie-like in the ranks of a ruthless, god-less foreign power, They were the enemy within—“the masters of deceit,” in J. Edgar Hoover’s chilling phrase. Hoover’s FBI joined forces with the House Un-American Activities Committee, citizens’ groups like the American Legion, and Hollywood personalities like John Wayne and Hedda Hopper. The rhetoric was as ugly and the witch-hunt as fierce and unforgiving as anything heard today. Those who refused to betray their principles and their friends were humiliated in public and stripped of their livelihoods without due process. HUAC, whose members took upon themselves the extra-legal role of judge, jury, and executioner, was at the vanguard of the inquisition. Newt Gingrich has seen and embraced the parallel: last June he called for the revival of HUAC to investigate alleged American supporters of the Islamic State and strip them of their citizenship.

High Noon’s screenwriter, Carl Foreman—himself a Jew, a liberal, and an ex-Communist—was called to testify in September 1951 in the midst of the film shoot, and he turned High Noon into a blacklist allegory, with himself as the brave marshal standing up to the evil gunmen of HUAC and its allies. But his allegory was also deeply cynical about bourgeois democracy—in Foreman’s screenplay, the good folks of Hadleyville turn their backs on the marshal out of cowardice and complacency. Rejected and outnumbered, he is left to face the evil by himself. This mirrored Foreman’s own experience: friends and business partners shunned him out of fear of being accused of Communist sympathies.

We love Westerns because they tell us we are a good people who defied overwhelming odds, built a good country in an untamed wilderness, and triumphed over evil. This is our foundational myth—the national fairy tale we tell ourselves about ourselves. In it, we are all Gary Cooper, proud, dignified, vulnerable, but fundamentally decent as we confront and defeat the bad guys. It’s no surprise that presidents from Dwight Eisenhower to Bill Clinton have loved High Noon, nor that a Wall Street Journal editorial cited Cooper when it praised the intuitive courage and selflessness of three young Americans who thwarted a terrorist attack on a train going from Amsterdam to Paris in August 2015. The editorial’s headline: “Gary Cooper in Europe.”

Donald Trump surely nurses fantasies of himself as the lone marshal standing between decent folk and the rapacious gang of corrupt politicians and self-interested bureaucrats who seek to destroy the country. Faced with what he sees as an imminent threat, Trump has quickly embraced an even more dubious American tradition: shoot first and ask questions later.

Cowed by the fear of Communism and its invisible tentacles, Americans during the Red Scare era were willing to stand by while a few demagogues and hucksters trampled on civil liberties in the name of national security. Liberal institutions that should have acted as a counter-force to protect American values—such as the courts, the press, and the opposition Democrats—largely failed to coalesce until the abuses became so blatant that they were shamed into action.

Many of us have faith in America’s fundamental decency. Sooner or later, we believe, the ship of state rights itself. It did so eventually during the Red Scare when the courts and the politicians eventually took a stand. President Eisenhower quietly pushed for the censure of Joseph McCarthy after the Commie-hunting senator impugned the integrity of the Army and more than two-thirds of the U.S. Senate voted for censure. But this time the ship may be out of control. After all, Joe McCarthy never got to be president.

Perhaps the most important lesson of the Red Scare is that the lone hero, standing defiantly on the edge of the frontier, is an empty and dangerous romantic notion. What’s needed to save our country, history teaches us, is a collective response by a majority prepared to insist that democratic values must prevail no matter who’s sitting in the marshal’s chair.

Glenn Frankel is author of High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic, published by Bloomsbury on Feb. 21.