When Tracey Emin introduced herself, she was soft-spoken, almost demure—it wasn’t exactly the British bad-girl artist I was expecting. “Hi, I’m Tracey,” she said with a smile. Then she fixed herself a cup of tea. Her hair was pulled back; she was wearing a gray fleece pullover, blue jeans, and sneakers (not “Chucks” or old school Pumas, but the kind you put on expressly for the gym). She sat down at the front desk of Lehmann Maupin’s Lower East Side gallery, where her solo show of new work is up through December 19, her pant leg inched up, revealing socks with cartoon cats and hearts printed on them.

Emin seemed pleasant, tepidly confident, and, dare I say, even a tad uncool—but in a good way. It was hard to believe that this is the same artist who has spent much of her career associated with terms like “wild child,” “provocateur,” “diva,” and “enfant terrible.” And these titles weren’t exactly undeserved. Emin palled around with Kate Moss, spending nights on the town that would make Amy Winehouse blush; she once caused a drunken scene on live TV after the 1997 Turner Prize awards dinner; and her artistic oeuvre includes a urine-soaked bed, watercolors inspired by her own abortions, and a tent in which she stitched the names of all her past lovers.

And yet, Emin seems to have truly mellowed—she notes at least twice that she’s pushing 50—and her latest work has, in a sense, too. She’s focusing on line quality and has returned almost exclusively to sewing and drawing. She’s happy with the new pieces; she feels like she’s getting back to her roots, so to speak—something she attributes to the process of planning her recent career retrospective, Tracey Emin: 20 Years, which made two European stops last year.

“It’s like Rudi Fuchs, this art historian said to me, ‘Be more bleak with your salty line; use your salty, salty line,’” Emin says. “It’s such a sexy thing—it’s brilliant. And I think now that’s what I’m doing much more. It’s like the difference between a woman with a really angular, strong face and a very pretty, sort of Brigitte Bardot. I’m never going to be the pretty girl. And that’s what was needed in my work—for that to come out and for it to become more angular, more intense, like I am. Plus we’ve got this massive recession on, so it’s like I’ve got nothing to lose.”

But even “mellow” is a relative word when it comes to Emin. Her work is still hyper-sexual (and hyper-personal, for that matter). But the neons, drawings, embroideries, sculptures, and film on view at Lehmann Maupin feel quiet and introspective, much like Emin herself these days.

Click Image Below to View Our Gallery

The artist is showing large- and small-scale hand-sewn embroideries on the gallery’s second floor. They depict women from the neck down, mostly, in various stages of self-pleasuring with Emin’s distinct scrawl stitched banner-like above and below. (“More ugly—More self—More mirror—No more inside—Just fear—More fear,” reads one; “No Not Right Now,” begs another). A video projection downstairs animates this imagery to squirm-inducing effects. Emin confesses that while the animation is based on her body, it’s not her masturbating, per se: “I wish it was,” she says, almost somberly. “I’m approaching 50 and my sex drive is not what it used to be.”

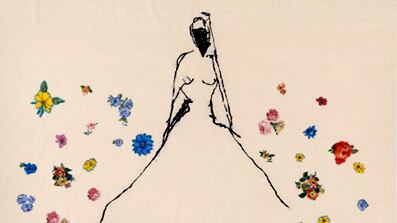

Big embroidered blankets dominate the space downstairs, bearing imagery that’s a bit more intricate—a bride with a blacked-out face, a rape scene, a man riding a giant dog. Emin explains that the two tall wooden sculptures in the middle of the room are tide-markers. (“No one fucking gets it!” she says with a laugh). They are meant to mirror her “salty” lines and evoke her childhood in Margate, which she likens to New York’s Coney Island.

Two obtuse neon signs hanging opposite one another on high walls, both in Emin’s slanted handwriting, are supposed to tie everything together. The phrase “Only God Knows I’m Good” (also the show’s title) is emitted in white light; “Some Crazy Fucked Up Dog Like Hell. That’s How it Feels to Live without Love” is across the way in a demonic reddish-orange.

Emin is certainly aware of her critics (and there are many of them). But she feels good about this show, her first in New York in almost five years. She isn’t scared in the same way she was last year when her retrospective opened.

“I entered the retrospective thinking, ‘Fuck, if I get slammed for this I’m in big trouble and I don’t know if I can handle it,’” she says. “It made me want to run away and cry. If you have 20 years of work and they say it’s bad, you’re in serious trouble.”

The results were mixed but not nearly as nasty as the response to her 2007 Venice Biennale showing (about which the Telegraph’s Richard Dorment wrote: “For the 22 years I’ve been reviewing this Biennale, I’ve never seen such thin material at the British pavilion”). It gave her the confidence to go back into the studio, she says, and to stick it to her critics. After all, it’s been 20 years—love her or hate her, Tracey Emin is certainly not going away now.

Rachel Wolff is a New York-based writer and editor who has covered art for New York, ARTnews, and Manhattan.