We all learned a lot from the economic devastation of the past few years, right? We examined what went wrong and how to do better in the future.

Um, not necessarily. Already, the scare of the last few years is beginning to fade—just look at the pushback to the regulatory reform legislation. There are many reasons for this. But one is that as Americans, we don’t like concentrating on our failures—we are much happier to focus on our successes.

That’s not true for every culture; in fact some learn more from their failures than accomplishments. Some fascinating research demonstrates this point. It turns out that North Americans—including our northern neighbors—have a very different mind-set when it comes to success and failure than Asian (and particularly Japanese) cultures.

Take one study that asked Canadian and Japanese undergraduates to take a test, which they were told was to assess the connection between creativity and emotional intelligence.

After it was over, some students were randomly told that they had failed, and some that they had done very well. The experimenter then explained to the participants that the next phase of the study involved an emotional-intelligence test on the computer. However, the computer then crashed (this was planned). The experimenter left, ostensibly to find help, and told the students they could work on another set of test items similar to the one they had just taken, although this would not count—it was just a way to kill some time.

The experimenter then went to an observation room to watch the participants without their knowledge through hidden cameras. The results: The Canadians who thought they had scored well on the first test—in effect who were successful—persisted significantly longer on the second task than those who thought they had failed. In stark contrast, the Japanese who believed they had succeeded were far less persistent on the second test than those who thought they had done poorly.

Bill Gates: “Success is a lousy teacher. It seduces smart people into thinking they can’t lose.”

Further studies along these lines with other variables thrown in demonstrate that failure tends to serve as a motivating factor for Japanese, while Canadians (and this has proved true for Americans as well) are more inspired by success. Researchers theorize that’s because for the Japanese the process is as or more important than the final result, so they focus on their areas of weakness as a way to improve themselves. North Americans, on the other hand, would much prefer to maintain a positive self-image by avoiding tasks that they feel reflect badly on them.

So—what difference does this really make? Why shouldn’t we be motivated by doing well and wanting to do better? Yes, but if we are too eager to ignore our mistakes and failures, we can’t learn.

Take the latest economic crisis: Too many people, considered by themselves and others to be financial geniuses, believed they couldn’t do wrong. And too many of us who were making money didn’t want to look behind the curtain. We know what happened. Executives confidently went on making multimillion-dollar mistakes and the culture was all about "proving rather than improving" their abilities, as one social scientist said.

Very successful professionals tend toward perfectionism—not just doing a good job, but being the best. The flip side of the drive for success, however, is the fear of failure and the tendency to feel shame and guilt when they do fail to meet their high standards. Because if failure is seen as a nasty secret and only success is worshipped, then people have no reason to go back and look at what they did wrong and try to figure out how to operate better. This is especially true for high-fliers, who rely heavily on the image of ongoing success.

But we have to learn to not buy into that image. Warren Bennis, a pioneer of the contemporary field of leadership studies and adviser to four presidents, says the learning person looks forward to failure or mistakes, "The myth asserts that people either have certain charismatic qualities or not," Bennis says. "That’s nonsense; in fact the opposite is true." Of the 90 leaders studied by Bennis, a common theme was that they demonstrated persistence, commitment, and risk-taking, but above all, learning.

"The worst problem in leadership is basically early success," he says. "There’s no opportunity to learn from adversity and problems." Or to quote the oracle Bill Gates: "Success is a lousy teacher. It seduces smart people into thinking they can’t lose."

In fact, people who are truly great at what they do—whether it be athletes, musicians, or chefs—concentrate on what they’re doing wrong in order to get better. Jonah Lehrer, in his book How We Decide, examined the success of Bill Robertie, who is a grand master in chess, a world-class poker player, and a world champion backgammon player. Lehrer notes that after Robertie plays a chess match or a poker hand or a backgammon game, he painstakingly reviews what happened.

"Every decision is critiqued and analyzed," Lehrer writes. "Even when Robertie wins—and he almost always wins—he insists on searching for his errors, dissecting how those decisions could have been a little better. Mistakes aren’t to be discouraged. On the contrary, they should be cultivated and carefully investigated."

As we climb out of the economic disaster of the last few years—and many people aren’t climbing at all, but still sinking—it will be a tragedy if we once again allow ourselves to be convinced that there are people who just can’t make mistakes.

Plus: Check out Book Beast for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

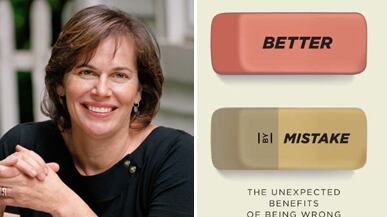

Alina Tugend has been a journalist for more than 25 years and has written about education, environmental issues, and consumer culture for The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, The Atlantic, the American Journalism Review, the Chronicle of Higher Education, Education Week, Child and Parents. Since 2005, she's written the ShortCuts consumer column for the Times. She lives outside New York City with her husband and two sons.