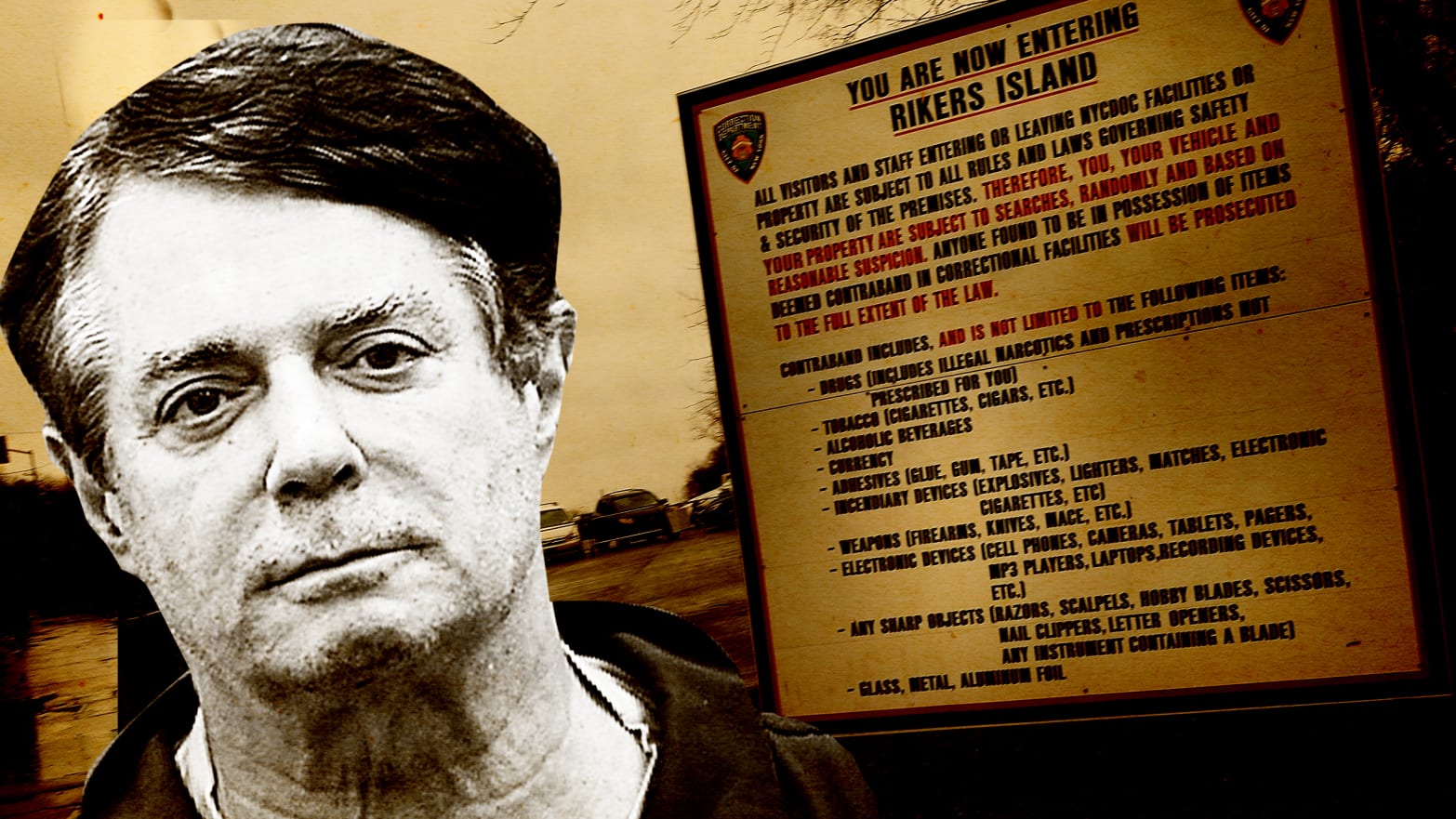

Less than three years after he was the presidential campaign chairman for Donald Trump, Paul Manafort is about to be transferred from a low-security Pennsylvania prison to New York City’s notorious Rikers Island to face trial on additional state charges here.

From what I saw in five years working for the Mental Health Department there, I expect the 70-year old former political high-flyer is in for a shock. The worst of his previous experiences behind bars might not seem so bad in comparison to the gloomy island where he’s headed.

Rikers, a complex of aged and decrepit jails that sit on a 415-acre island in the northern region of New York City’s East River, functions primarily as a pre-trial holding facility for criminal defendants who are awaiting resolution of their cases as they wind slowly through the courts. During this time, they not only agonize over the eventual outcome of their case, but they must also survive Rikers—and for a high-profile inmate like Paul Manafort this will be especially difficult.

I saw many high-profile inmates come through the jails, where they were routinely held in protective custody for their own safety. Reassuring as this may sound,“PC” is actually a double-edged sword: these inmates are well protected from everyday jailhouse violence, but to ensure this safety they are segregated from the general population and confined to a cell where their existence becomes tantamount to solitary confinement.

As former acting chief of mental health in the solitary confinement unit, I have seen firsthand just how grim this can be, and how easily people can unravel under its duress. Manafort will likely face 23 hours a day in a cell the size of a parking space, furnished with a cot, a footlocker, a tiny metal sink and toilet. There will be no desks or phones, like he boasted about as part of his “VIP” treatment in a previous lock-up. Food will be passed on a tray through a flap in the cell door. A small mesh-covered window will transform any outside sunshine into grayness.

Depending on which jail he is assigned to—a location which will be shrouded in secrecy—he might glimpse a few passing seagulls, but will likely see nothing more than the side of another jail.

And then, there’s the heat. Manafort has the misfortune of arriving on the damp, muggy island just as the mercury is creeping up. The idea of air-conditioning on Rikers is laughable, and the old brick buildings heat up like ovens. As stifling as the jails become, nowhere is the misery greater than in the closed cells—solitary confinement and protective custody.

I well remember the sight and sounds of the frantic occupants inside these cells—of sweaty palms sliding down the little plexiglas windows, voices crying out, “Help, help, please—we’re dying in here.” I requested that they receive pitchers of ice water. Request denied. The tiny sinks with their dribbles of lukewarm water would have to suffice.

At Rikers Island, the Mental Health Department was a constant presence in the solitary unit. We had a saying: “If they had no mental health issues before they entered solitary, they do now!” Like so many others in isolation, Manafort will inevitably struggle with depression, sleeplessness, and anxiety. Hopefully, he will get the support he needs to survive it.

Within the next 10 years, the scandal-plagued Rikers Island is slated to finally be closed. It will be replaced with modern and more humane borough-based facilities. Unfortunately, the closure will not come in time for Manafort.

In the meantime, like every other inmate on Rikers, the best he can hope for is that his cases will resolve quickly.