MOSCOW— Why did Ukraine decide just now to challenge Russia’s growing presence in a small body of water near Crimea? Why did Russia turn its guns on Ukraine’s little gunboats on Sunday and seize three of them along with their crews?

Could this be the prelude to a wider war?

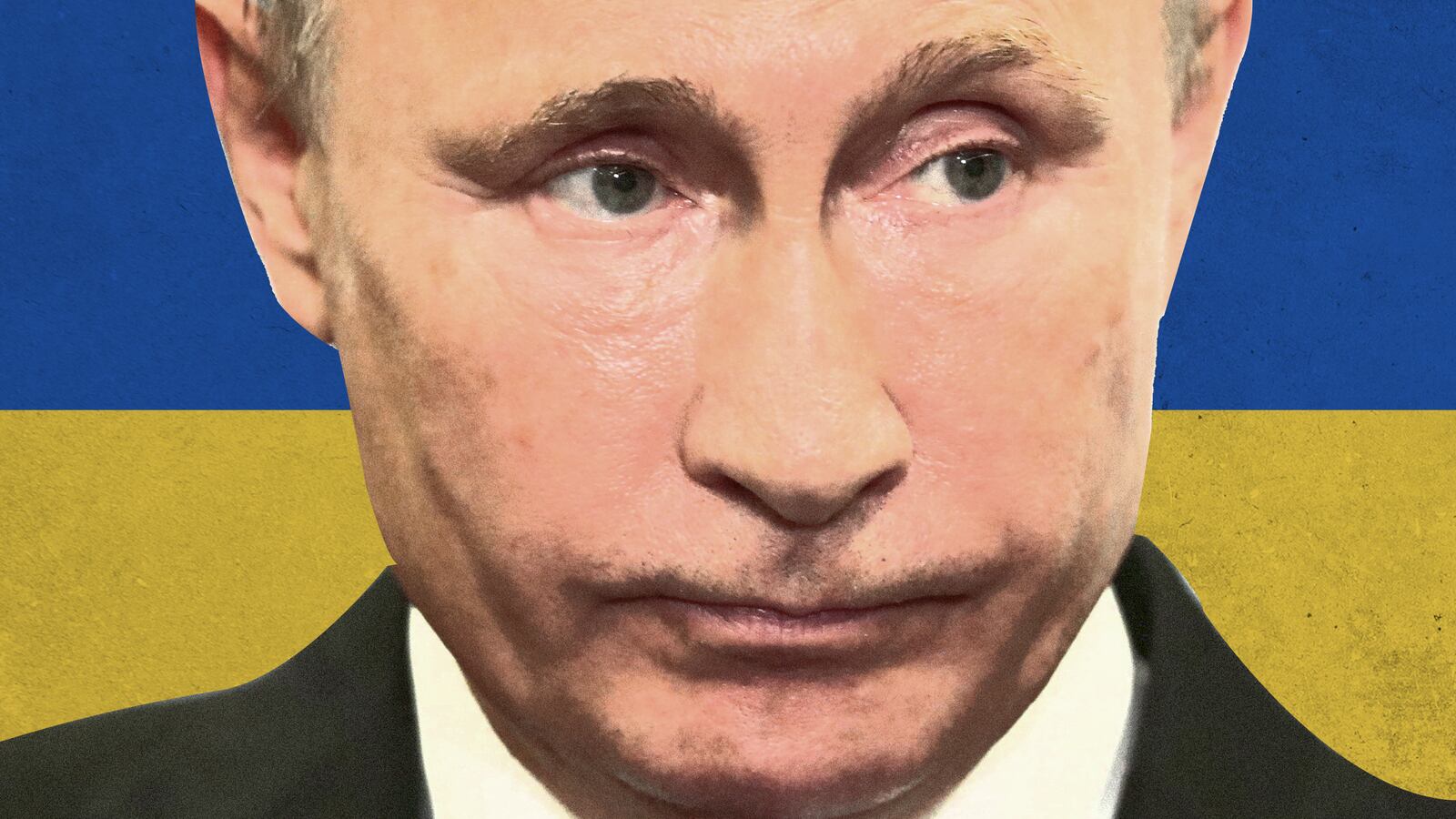

How far will Russian President Vladimir Putin push the confrontation? What will he say when he meets Donald Trump and other leaders at the G20 summit at the end of the week? What will Trump say to him? And why on earth is Trump equivocating when his top diplomats are denouncing “aggressive Russian actions” and “reckless Russian escalation”?

"Either way, we don't like what's happening, and hopefully, it will get straightened out," Trump told reporters Monday, more than 24 hours after the incident. "I know Europe is not—they are not thrilled. They're working on it too. We're all working on it together."

"Either way"?

The answers to these questions are not always clear. But a bit of history is required if we’re going to begin to understand the tense, potentially explosive confrontation developing between Russia and Ukraine—one that has NATO worried and rumbling while Trump falls back on his “both sides” brand of reasoning.

We now know, because Putin would later admit it on state television, that in 2014 at the height of Ukraine’s revolution, on the very day in February when Putin’s ally, President Viktor Yanukovych, fled the country, Putin ordered his commanders “to begin work on returning Crimea to Russia.”

It had been part of Moscow’s empire under the czars, and then under the Soviets, who had transferred it to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic — an administrative move that suddenly took on huge strategic and nationalist importance after 1991 when the Soviet empire collapsed and Crimea remained part of independent Ukraine.

As the Maidan revolution in Kiev moved the country into the orbit of the European Union and potentially of NATO in the winter of 2013-2014, a common refrain among Russian politicians became, “If Ukraine escapes to the West, then Crimea should come back home.”

And within days of Yanukovych’s departure, the peninsula was full of “little green men”—in fact burly soldiers wearing masks and unmarked uniforms—with the newest communication equipment and Russian weaponry. They controlled a hasty referendum in Crimea, and unsurprisingly a majority of voters supported merging with Russia.

By March of 2014, 445 out of 446 Russian Parliament members voted in favor of Russia’s annexation of Crimea. In the process, Ukraine lost about 80 percent of its navy and only about 6,000 out of 20,000 Ukrainian army soldiers, sailors and members of the coast guard, police and special services returned to the Ukrainian mainland from the annexed peninsula. The rest defected to Russia.

Other people fled into mainland Ukraine. Today at least 40,000 Ukrainian citizens cannot return to their homes on the Crimean peninsula, including thousands of Crimean Tatars.

A few weeks after Crimea was annexed, masked men in new green uniforms appeared in the largely industrial region of eastern Ukraine known as Donbas, and a war began between Ukrainian and Russia-backed rebel forces, including Russian recruits and Russian army officers who officially were “on holidays.”

What happened on Sunday was one more milestone—and potentially the most dangerous—in this now five-year-old, undeclared war.

Former U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine John Herbst, now with the Atlantic Council in Kiev, calls this “a significant escalation.”

“Before, Moscow always denied in real time that its soldiers were involved,” Herbst said in a conference call. There were no “little green men” this time around. “Here in the light of day Russian naval vessels attacked Ukrainian naval vessels.”

Herbst said the engagement was “unprovoked.”

But nothing is ever quite that simple in the Ukraine conflict.

The new crisis between Kiev and Moscow, like those that came before, is partly aimed at winning the narrative in Western capitals where there is only a dim appreciation of the critical geography:

The Crimean Peninsula is very nearly an island, connected to Ukraine’s mainland in the north by a single road running through reedy marshes. In the southeast, a finger of land near the town of Kerch seems to reach out toward another finger coming from the Russian mainland, but it doesn’t quite make it. The water in between, known as the Kerch Strait, is the only gateway to the shallow, nearly landlocked Sea of Azov, and on its shores are two of the most important industrial ports of Ukraine: Berdyansk and Mariupol, which is near the front lines of the ongoing war in the east of the country.

After Putin annexed Crimea, direct Russian access through Ukraine was impossible. Supplies coming straight from Russia had to be brought by air or sea, and when the Donbas campaign stalled there was no chance to secure a new land route through breakaway republics.

So in 2015 the Kremlin started building a 12-mile long bridge across the Kerch Strait, fulfilling a dream dating back to Russian Emperor Nicholas I and cementing the nationalist vision shared by the pro-Putin part of the Russian electorate: “Crimea is ours.”

In May last year Putin inaugurated the Kerch Strait bridge. The construction that cost Russia $4 billion was over, but the battle over the sea behind it continued.

Since 2003, according to Herbst at the Atlantic Council, the Russians and Ukrainians have agreed that while the Black Sea is international water, the Sea of Azov belongs to both of them, and under that arrangement they can inspect each others’ shipping. Since April this year, Russian inspections have grown much more aggressive and according to Herbst there has been a dramatic drop in commerce from the Ukraine ports. The Russians also deployed an increasing number of warships, Ukrainian officials say.

Kiev saw this as Putin trying to turn the Azov Sea into a Russian lake, and some Russians are inclined to agree.

“What we saw on Sunday is Putin’s struggle to control the entire Sea of Azov. See, he did it in his classical style: by shooting, seizing and taking hostages,” Moscow municipal deputy and opposition leader Ilya Yashin told The Daily Beast.

In Kiev many wondered if the West was going to back up Ukraine, not just with words but with actions.

In 2008, during a week-long war between Russia and Georgia, President George W. Bush sent a U.S. Coast Guard vessel, the Dallas, to Batumi port, just 125 miles away from Russian ships. That put the end to the hot phase of the war in that Black Sea republic.

Russian analysts speculating about Washington’s reaction to the crisis wondered if Trump would cancel any planned meeting with Putin. “I am convinced that Trump is going to swallow Putin’s aggression,” said Yashin. You will see, he will meet with Putin at the end of this week as if nothing has happened.”

More than 24 hours after Russian forces captured those three Ukrainian gunboats the West had not demonstrated any significant support for Kiev, Yashin noted. “That is exactly what Putin counted on.”

Herbst was not quite so pessimistic about the eventual reaction from Washington, which could stiffen sanctions or take a range of more aggressive measures. “Of course [in the past] Trump’s statements on Russia have been peculiar, to use a diplomatic word, but his administration’s policies have been tough.” Under Trump, Ukraine received American Javelin anti-tank missiles. Herbst suggested now might be the time for it to get more anti-ship and anti-aircraft missiles. The idea would be to show Putin that Russia’s security was hurt, not helped, by his current tactics.

Ukraine’s internal politics, meanwhile, are not likely to help calm the situation.

On Monday, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko signed a decree declaring martial law. On Monday evening the country’s parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, voted in support of the bill, which gives significant power both to Poroshenko and the Ukrainian military.

“The martial law does not mean a declaration of war,” Poroshenko said, addressing the nation. “Ukraine is not going to war with anyone.”

Kiev was in talks with NATO officials and with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who had promised to do everything to defuse the standoff between Ukraine and Russia.

Meanwhile, hundreds of far-right nationalists and militia, many in camouflage and waving black flags, flooded the streets of Kiev. Apparently itching for a fight, they demanded Ukrainian authorities break diplomatic relations with Russia. During a rally on Sunday, somebody set a Russian diplomatic vehicle on fire.

Many activists protesting outside the Rada and the presidential administration building were veterans of the devastating war in Donbas, which has claimed the lives of more than 10,000 Ukrainians, including 2,800 civilians.

Nearly 2 million people have been internally displaced from Crimea and Donbas regions in eastern Ukraine, and from the early months of the conflict the Ukrainian military has been demanding martial law as an official recognition the country was at war.

Young veterans complained about the political elite benefiting from the war and conducting business with the Russia-controlled territories.

All this raises suspicions among Poroshenko’s critics about the decision to challenge the Russian rules for traffic in the Sea of Azov. “I think there is an unfortunate tendency in Ukraine and not just in Ukraine for politicians to play political games with national security issues,” says Herbst. “But I don’t think that is the case with this.”

On November 23 the Ukrainian navy began its planned redeployment, moving the gunboats Berdyansk and Nikopol, as well as the tugboat Yani Kapu from the Black Sea port of Odessa to the navy base in the Sea of Azov near the city of Mariupol.

Herbst says his understanding is that the ships notified the Russians of their intention to pass through the strait, “but only on the 25th, not earlier than that.” He said his belief is that the Russians wanted the Ukrainians to fight back in a much bigger incident, in effect drawing them off sides. “They tried to provoke Ukraine to take military action so they could take punishing retaliation,” Herbst suggested. “Moscow has been cultivating this crisis since April.”

But it’s also clear that Kiev set out to mount a challenge.

Russian officials said that at 5:45 a.m. the Ukrainian gunboat Berdyansk reported its intention to pass through the Kerch Strait and a commander of the Russian border patrol advised it not to proceed because the “peaceful passage through territorial sea of Russian Federation is temporary suspended.”

On Sunday, Ukrainian authorities published a video of what allegedly was a Russian ship ramming a Ukrainian tug. “Smash him from the right!” somebody yells in the video. Ukrainian Internal Affairs Minister Arsen Avakov said on Twitter that the footage “will be submitted as evidence to the international court."

Mariupol, a big industrial center and Ukraine’s key port in the Sea of Azov, has been suffering from the conflict ever since Russia-backed rebels attacked the city in 2015. Local activists and volunteers struggled to keep the Ukrainian army in Mariupol, protested against demilitarization of their besieged city, and helped soldiers in the tranches with equipment and food.

“I saw this war coming here to the Azov Sea for years,” Galina Odnorog, a Mariupol activist told The Daily Beast. “We have been screaming about Russia trying to take over our region but nobody would listen to us.”

Ukrainian soldiers based in Mariupol are preparing for new battles. “The martial law bill does not change our life much, we continue to dig trenches, we are ready, we’ve been living with the war for four years,” Odnogorog said. “We receive many calls from worried people. But we tell them not to panic.”

Moscow, in its turn, began to air confessions by captured Ukrainian sailors admitting that they had “entered territorial waters of Russian Federation,” in spite of warning from the Russian vessels.

The Kremlin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov said that the Federal Security Service, the FSB, “acted in accordance with state law.” The FSB blamed Ukraine for “prepared and orchestrated provocations... in the Black Sea” and promised to release some materials to support that argument.

Poroshenko’s critics in Moscow suggested that the martial law decree was a political move aimed to postpone the presidential elections. “The timing is perfect, Poroshenko played his cards right, by this decree he cancels the election campaign, which he otherwise would have lost; and he spoils Putin’s meeting with Trump planned for this week,” pro-Kremlin analyst Sergei Markov told The Daily Beast.

“The Kremlin always tries to change the subject from what is happening on the battlefield to what is happening in Ukraine’s political system,” said Herbst.

On Monday afternoon Ukrainian authorities announced that in spite of the crisis, the presidential elections will take place on March 31, 2019.

— With additional reporting by Christopher Dickey