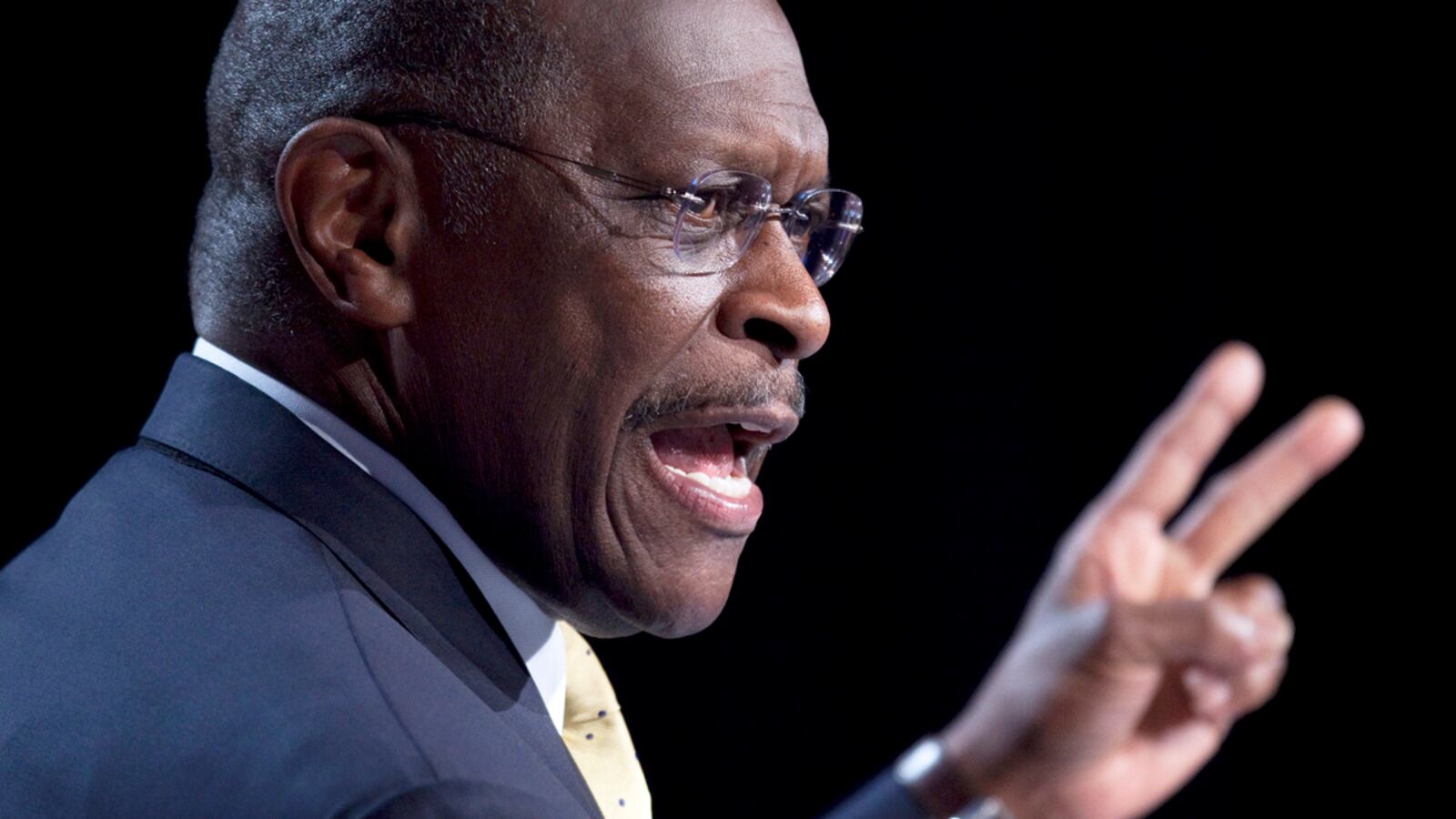

Herman Cain’s much-touted 9-9-9 plan, which is fueling his surge to frontrunner status, is a radical departure that would generate plenty of problems, from slashing federal revenue to making it more expensive for the poor to buy everyday goods.

That, at least, is what many economists across the spectrum say after studying the sketchy outlines. But not to worry: senior aides in both parties say such a scheme would have 0-0-0 chance of passing Congress.

The plan, which became a major focus of Tuesday’s GOP debate in New Hampshire, has the appeal of simplicity. “I can explain it in a minute,” Cain told The Daily Beast. “All taxpayers play by the exact same rules. That’s what people love about it.” The question is whether they will be less enamored once they learn some of the details.

The one-minute explanation: corporate taxes, now close to 40 percent, would be cut to 9 percent. Federal income taxes, now as high as 35 percent, would be cut to 9 percent. And consumers would pay a national sales tax of 9 percent for all products, on top of any state and local levies—bringing the total in New York City, for instance, to 17.875 percent. (It’s not clear whether services would be included.)

That’s good news if you’re a big company or upper-bracket taxpayer, but not so much if you’re a low-income working stiff. While Cain denies that his plan would be regressive, the working poor tend to spend most or all of their pay, which would be taxed every time they buy something. Michael Ettlinger, a vice president at the liberal Center for American Progress, says the plan would impose “the biggest shift from the wealthy to the middle class in the history of taxation, ever, anywhere.”

That’s not just the left-wing view. Bruce Bartlett, an adviser in the Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations, says that 9-9-9 is unfair to working taxpayers. “It’s the most upside-down tax plan that’s been put forward to tax the poor and the middle class,” he says. “It’s rather insane it’s gotten as much attention as it has. It’s a waste of my time to attack it.” What’s more, Bartlett says of what Cain has made public, “there is not nearly enough information on which to do a serious analysis.” The Cain campaign wasn’t answering questions about it on Wednesday.

Daniel Shaviro, a New York University law professor who specializes in taxation, calls the plan “not viable.” For rich people—defined as those who work for themselves and don’t have to take a salary—it essentially becomes an 18 percent total tax on all money. But for poor people collecting a paycheck, Shaviro says, it amounts to a 27 percent tax. “It’s a disservice to public debate to have people think it’s so simple,” he says.

Then there’s the question of who is covered. At the moment, just under 50 percent of all those filing returns pay no income taxes, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation. They would be hit with the 9 percent sales tax.

But that is a plus, in Cain’s view. “Everybody’s going to pay less taxes,” he insisted in a recent interview. “When you’ve got more people paying taxes, everybody’s got some skin in the game. But because the base is bigger, everybody’s net taxes will go down.”

That expectation seems to rest in part on the logic of the old Laffer curve, the Reagan-era theory that if you cut taxes, you liberate the economy and more money flows into the Treasury. But “there’s not one iota of evidence to show that that works,” says Bartlett, noting that the Bush tax cuts simply blew a bigger hole in the federal deficit.

Speaking of the deficit, the former pizza executive claims his plan would be revenue-neutral. BusinessWeek estimated that his approach would have brought in $1.96 trillion, based on 2010 figures, compared to $2.16 trillion in actual tax collections; others say the gap would be far wider.

Getting rid of the payroll tax, as Cain proposes, would undoubtedly be popular. So would blowing up the capital gains tax, especially for those with big holdings in stocks and bonds, and the estate tax, for those with sizable sums to leave to their heirs. And corporations will love that profits earned overseas can be brought back to this country tax-free.

But with Cain eliminating most other tax deductions, including the break for home mortgages, every special-interest lobbyist on the planet would try to modify or block the measure. And that means 9-9-9 would have no hope of becoming law in its current form.

“The reason it would never happen is that any overlay of a consumption tax on top of an income tax is an absolute nonstarter for conservatives,” says a senior Republican staffer on the Hill. “It is a way for Washington to stealthily continue to raise taxes. Everywhere there is a value added tax and an income tax, the VAT continues to creep up and is a way for a government to increase taxes.”

Former Sen. Rick Santorum pressed this argument in the debate, saying: “How many people believe that we’ll keep the income tax at 9 percent? Anybody?” Cain countered that he would ask Congress to require a two-thirds vote before the tax could be raised.

Another major concern: “It’s unclear how much revenue 9-9-9 would bring in,” says the GOP staffer. “In times of debts and deficits like we’re in today, Republicans could not enact something that would decrease revenue levels because we would go further into debt.”

A top Democratic House staffer offered a similar verdict: “From what we know about it, it would be a tax shift to the middle class and to the lower class. It’s pretty obvious that something like that would be dead on arrival.”

Still, the notion of simplifying the tax code is a popular one in conservative GOP circles. Rep. Rob Woodall, a freshman from Georgia, introduced a national consumption tax bill this year with 47 co-sponsors, all Republicans. Woodall would replace all income, corporate, capital gains, and estate taxes with a 23 percent levy on goods and services. (He would subsidize those living below the poverty line by sending them a “prebate” check to cover basic living expenses.)

Rep. Michael Burgess of Texas is pushing an alternate plan to allow individuals and corporations to opt out of the current system and instead pay a 19 percent flat tax for the first two years, followed by a 17 percent rate tax after that.

For all its sudden notoriety, the Cain blueprint is only what he describes as Phase 1. In Phase 2, Cain says he would “end the IRS as we know it” by junking individual and corporate income taxes altogether and replacing them with a consumption tax. Why doesn’t he propose that now? A posting at the Tea Party group FreedomWorks says the rate, to raise enough revenue, would have to be around 25 percent for everything you buy—and that would cause “sticker shock,” especially for lower wage-earners.

Cain had trouble selling his centerpiece recently on Fox News Sunday. “It looks to us like under your plan, corporations and the wealthy will pay considerably less than they currently do, and lower-income people particularly, the 45 percent, roughly, of Americans who don’t pay income tax now will end up paying a lot more,” host Chris Wallace said.

Cain was quick to challenge that accounting. But if he continues his surge—and he has a 4-point edge over Mitt Romney in the latest NBC/Wall Street Journal poll—9-9-9 is going to get far more scrutiny than when he was a sideshow candidate with a catchy slogan.

Patricia Murphy and Daniel Stone contributed to this report.