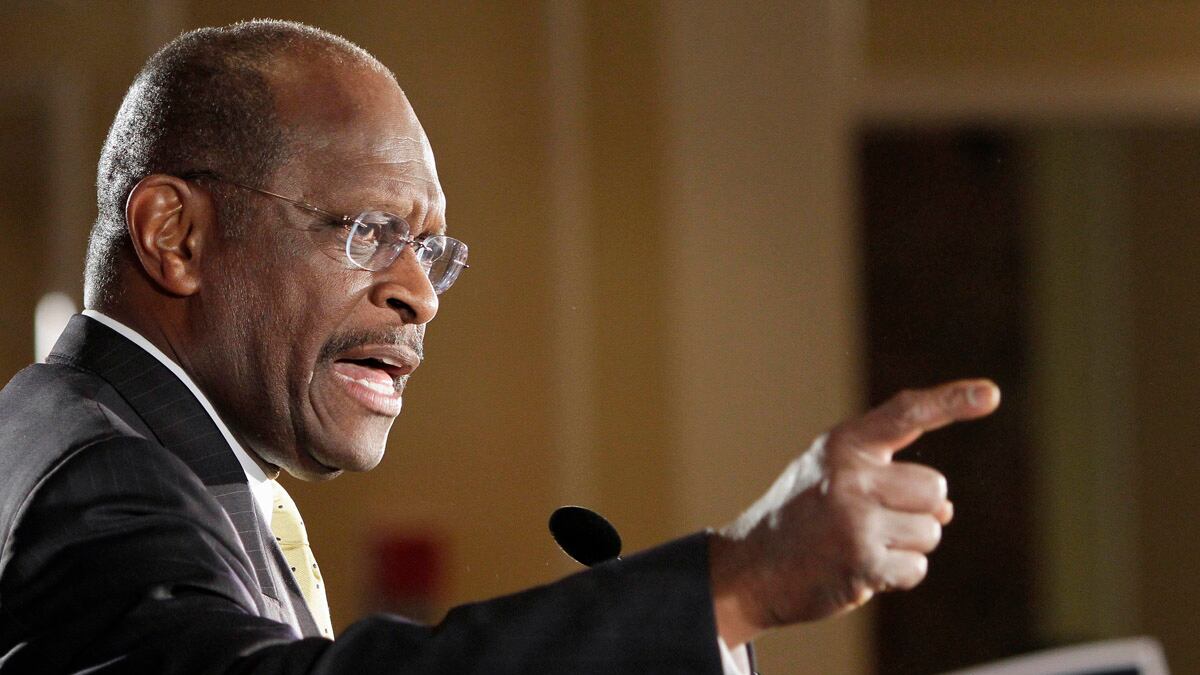

Two days after Herman Cain won a stunning victory in September’s Florida straw poll, Richard Green maxed out, giving $2,500 to Cain’s campaign committee. Green was the longtime CEO of two related Missouri energy companies whose boards Cain served on for nearly two decades, Utilicorp United and Aquila. And when Green wasn’t running the companies, his brother Robert was. Since 2003, when Cain launched an unsuccessful Senate campaign, the Greens have donated $10,500 to various Cain campaign committees. Other executives at Aquila/Utilicorp and an Aquila PAC added another $12,500, making it one of Cain’s biggest sources of campaign cash.

But that 90-year-old, multistate, publicly owned but family-run conglomerate, with 300,000 Missouri electric customers alone, no longer exists. Now part of longtime rival Kansas City Power and Light, Aquila was acquired in 2008 by the utility’s parent company, Great Plains Energy, paying Aquila shareholders $4.54 a share for stock that peaked at over $37 in 2001. Utilicorp assets were acquired by Black Hills Energy in the same $1.7 billion deal, including the combined company’s natural-gas and electricity properties in four states other than Missouri.

Until its demise, however, Aquila/Utilicorp was a large part of Cain’s business life from 1991 on, while it was transforming itself from a conservative, asset-heavy, international energy company that owned power plants and distribution lines into a merchant energy commodity trader that soared and crashed in a speculative frenzy. The company never recovered from 2001, the best of times and the worst of times for Aquila. Claiming at the time that it earned more than $40 billion, Aquila later downgraded its 2001 revenue to $3.7 billion, implicitly acknowledging that much of what it and others like Enron did in the energy derivatives market was fantasy trading.

Over the course of these boom-to-bust-to-sale years, Herman Cain, the businessman who thinks his financial skills qualify him for the White House, became the longest-serving independent director of the company, and was eventually selected as the company’s official “leading independent director.” As chair of Aquila’s compensation committee, he oversaw the award of millions in bonuses to the very executives presiding over this disaster. Also a member of its nominating and corporate governance committees, Cain’s tenure with the company has been marred, like the rest of those in its leadership posts, by a swath of settled lawsuits and government findings against the firm.

While Mother Jones did a penetrating analysis of one of the suits in May, exposing how the company misled employees into investing their retirement funds in a stock gone volatile, the rest of the story of Cain’s Aquila adventure has gone untold in the national coverage of his presidential campaign. This Daily Beast investigation opens a new window into the business life of a candidate suddenly fading in the polls, and it is one dramatically different from the tough-guy, “CEO of self” posture that Cain takes in his new book, This Is Herman Cain. At Aquila, he was just one more go-along guy at the helm, rewarding the recklessness at the top that cost thousands of workers their jobs and damaged the value of the stock held by retirees and every other shareholder.

Even Richard Green conceded in a 2002 congressional testimony that the loss of 90 percent of the company’s stock value and the junk rating of its bonds that year was tied to just the sort of deregulation that candidate Cain still champions. A chagrined Green appeared at the hearing to endorse new energy-trading regulations that all but two Republicans in the Senate wound up voting against and blocking, singing the same deregulation song Cain delivers with Gospel certainty. Indeed, in 2008 Cain blogged in support of Phil Gramm for a cabinet post in the McCain administration even though it was Gramm who, in the 2000 Commodity Futures Modernization Act, created the very energy exemption that Richard Green was testifying should be ended, and Gramm again who led the 2002 resistance to closing the loophole.

As disturbing as Cain’s sexual-harassment complaints and foreign-policy deficiencies are, his prominent role at Aquila challenges the core of his candidacy, painting a picture of him as indifferent at the switch and willing to kowtow to corporatcrats, whom he assures us will occupy half his cabinet. In his book, the candidate starts a chapter titled “New Challenges and Achievements” with the assertion that his success at Burger King and Godfather’s Pizza “led to the recognition of my business savvy and financial acumen,” citing his appointment to corporate boards as the first evidence of this recognition, “starting in 1991” with Utilicorp and three others. He was named to the related Aquila board in 1992.

The Cain/Aquila saga starts with the bonuses he personally approved, the flip side of the “get-a-job” medicine he routinely doles out to Occupy Wall Street protesters and anyone else on the short end of the stick in the country he wants to lead. In February 2002, precisely when court records indicate that a suddenly sinking Aquila was planning the layoffs of 500 corporate and field staff, its Cain-chaired compensation committee awarded the two Green brothers $19.7 million in combined bonuses and payments, sparking a controversy that eventually led to a Securities and Exchange Commission probe. As if that weren’t enough, when Robert Green, who’d just replaced Richard as CEO in January 2002, resigned that October, Cain’s committee gave him another $7.6 million severance package, though the company had lost nearly 1,600 of its 7,300 employees during his abbreviated tenure. Cain’s board picked Richard to return as CEO. No one other than a Green had ever run this four-generation company since 1917, and Robert’s law firm at the time had long been a principal outside counsel.

Leo Pink, an energy executive described by the Kansas City Business Journal as a Green family friend, told the Journal that the Greens “appointed every person on that board, so they’re their kind of guys.” The complaint in one of the lawsuits Aquila settled alleged “the Aquila board had been handpicked by Richard Green and would rubber-stamp anything he wanted approved.” The Kansas City Star compared these bonuses with those awarded at 13 other energy companies that Aquila regarded as peers and put Richard Green’s package among the top three, much bigger than those awarded by larger companies like Duke Energy, whose earnings that year were five times Aquila’s. It also compared Richard Green’s bonus with the $1.7 million one he collected in 1997, when Aquila’s stock finished the year higher than it did in 2001.

In May 2003, a board audit committee launched a yearlong $3 million probe of these bonuses (and others approved by Cain’s committee, totaling $12 million, excluding the value of stock options simultaneously awarded). John Baker, who’d worked at the company for 47 years and was so close to the Greens that he was a trustee of their family trust, spearheaded the supposedly “independent” probe. Baker donated $2,000 to Cain’s Senate campaign while he was investigating the bonuses Cain awarded. Leo Morton, the executive who tried to explain the bonuses to the Star, had kicked in another $2,000 to Cain a couple of weeks before he talked to the paper, while Cain’s fellow compensation-committee members donated $6,000.

One compensation-committee member and campaign donor, Ivy Hockaday ($4,000), was also the longtime CEO of Hallmark Cards Inc., which is located near Aquila in Kansas City and is so intertwined with the Greens that Richard serves on the board of the foundation created by the Halls, the family that founded and still runs the company. Cain was named to Hallmark’s corporate board in 2001 when his fellow Aquila board member Hockaday was CEO of Hallmark and Donald Hall was Hallmark’s chair. The Hall family and another Hallmark director and his wife have donated another $29,500 to Cain campaigns, including $7,500 to the presidential campaign this year. Cain’s interlinked Aquila and Hallmark donations add up to $47,500, a sign of how significant his ties to these companies have been to his personal financial history.

Sometime after the bonus controversy exploded, Cain stepped down as compensation-committee chairman (the successor company, Kansas City Power, said it would provide the date but ultimately did not). Baker’s probe predictably supported the bonuses, and the SEC did not find any violation of law associated with the extraordinary packages.

When Richard Green faced a hostile shareholders' meeting years later, announcing the 2007 sale of the company, one speaker raised the specter of the 2001–2002 “near bankruptcy,” calling it “a failure of management and the board,” and pointing out that Aquila still had four board members left over from those days, including Cain, who also served on the corporate-governance committee. “I accept responsibility for that, and you are owed an apology, and I have done that and continue to do that,” said Green, acknowledging that the role of Aquila’s leadership in the downfall “no doubt shakes trust.”

On the campaign trail in New Hampshire this year, however, Cain took quite a different tack, claiming that Aquila “was a victim of the Enron meltdown,” oddly attributing the near collapse of the company to the bankruptcy of its top competitor. Rather than apologize, Cain credited the board and management with “saving the company from bankruptcy,” without mentioning that it was the same board and management that brought it to the brink, or that Aquila was forced into an immediate sale of many of its international and other assets, as well as an unappealing merger a few years later.

Cain’s campaign told Washington Post columnist Jennifer Rubin in October that the board “kept the management team to get through the restructuring,” contending that “restructuring is not the time for management to turn over” (apparently, except in the White House). The statement even supported the final $6.2 million cash and stock payout, plus a million-dollar-a-year pension, to Richard Green, as well as a $300,000-a-year pension for Robert, when the remaining shell of the company was sold, concluding that “the board saw fit to reward them for their efforts.”

Another shareholder at the pre-sale 2007 meeting complained that board members like Cain were still given 7,500 shares a year, right up to the approval of the merger with Great Plains Energy. Cain lists no stock in these firms or their successors on the disclosure form he filed as a candidate this August, but Aquila/Utilicorp holdings were once a substantial Cain asset. Cain was listed as the owner of 23,568 Aquila shares in 2002, when he approved the bonuses. His holdings grew to 36,068 shares in February 2003, growing faster than the usual 7,500 shares a year, and ultimately reached 77,771 shares at the time of the announced 2007 sale of the company. Cain was entitled to sell his Aquila shares when the merger was approved for more than $353,000, as well as receive shares in Great Plains. He also served throughout this period on the Utilicorp board, and, at some points in the complicated history of the two joined entities, separately benefited from that company as well.

Cain made $100,000 a year as an Aquila director and $120,000 a year at Hallmark. In addition, when he left Hallmark in March of this year, he was given a five-year retirement deal, though his disclosure form does not say what his quarterly pension payments are. The combination of his Kansas City board positions account for at least $3.5 million in income to him, compared with the $165,183 he reported earning from his radio show in the last half of 2010 and first half of 2011, and the $53,965 a year that Godfather’s Pizza is still paying him. Since Cain stepped down as the head of the National Restaurant Association in 1999, his principal source of income has been as a corporate board director, serving on four besides Aquila/Utilicorp and Hallmark, sometimes on the compensation committee. His Aquila performance apparently cemented his reputation as a board director whom a CEO could trust.

Cain’s attitude about executive bonuses, in any event, appears unchanged by his Aquila experience. He devoted a blog on his website in March 2009 to the controversy over the $165 million in bonuses AIG was paying out even as it collected billions in bailouts. Cain attacked legislation introduced by Sen. Chuck Schumer to tax the bonuses as the "bully bill,” charging that this “bonuses melodrama” was “all about deflecting the blame,” which he said was entirely due to the very new president and the Democratic Congress. “Some of us are not watching the sideshows” of these “evil undeserved bonuses,” he wrote.

This post was consistent with a host of columns he wrote that have attracted shockingly little media attention, including one as late as Sept. 1, 2008, in the middle of the collapse, headlined “Economic Growth Surges, but Democrats Ignore the Truth Again.” That July, Cain ridiculed “the mainstream media’s it’s-not-a-crisis-but-we-are-going-to-make-it-look-like-one banking crisis.” In one May radio appearance with right-wing hotshot Neal Boortz, Cain said “liberal leaders in Washington have demagogued the idea of a recession,” adding in a column that the economic woes were “a figment of our whiny imaginations” fostered by the Democrats and the mainstream media “because it feeds their theme of Bush hate.”

NBC’s Chuck Todd confronted Cain with bits of this record in October and Cain tried to obfuscate, admitting that he “missed” the “situation” in 2005 without mentioning how badly off the mark he was deep into 2008. He even said he “did not realize just how bad the whole bundling and derivatives thing was,” precisely the speculative merchant market that brought Aquila down. When Todd asked how he’d “reassure voters” since he “missed the economic collapse,” Cain said, “It’s real simple. I have economic advisers working with me now.”

Cain the candidate remains a defiant opponent of efforts to regulate financial markets, turning Dodd-Frank into a joke line at the CNBC debate and writing in June that government has to “get out of the business of over-regulating,” contending that “eliminating burdensome federal regulations would provide an immediate boost for our economy.” He devoted a section of his book to “excessive government regulations.”

These pronouncements run directly counter to what Richard Green said he learned from what he called the Aquila “collapse.” At a July 2002 hearing, Peter Fitzgerald, the other Republican senator who backed the reform bill, asked Green if he favored “greater regulatory oversight.” Green testified, “Oh, no question about it. What we have seen happen in the marketplace and the colossal breach of trust by corporate America, we have to start building it back. That is why we are in favor of your amendment.” Green insisted that Aquila “did not engage in the kinds of improper accounting or trading practices for which Enron has become notorious,” claiming that it “played by the rules.”

But a year and a half later, Aquila agreed to pay $26.5 million to settle charges brought against it by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) for engaging in precisely the same sort of revenue-inflating, circular, “nonexistent trades” as Enron, as well as paying $76,000 in separate penalties for “gaming” violations to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Its CFTC payment was the third-highest of all the fined energy traders, behind only Enron and Duke, and though Aquila settled without admitting guilt, it also agreed not to deny that it had “knowingly delivered false trade information to skew the indexes to benefit” its trading position. It was charged with these make-believe futures, options, swaps, and derivative trades through June 2002, continuing even after the bonuses were paid. In addition to doing wash or round-trip trades itself (where one company buys and sells the same amounts of natural gas or electricity from or to another at the same time at the same price, just to juice revenue numbers), Aquila was part owner of the Intercontinental Exchange, or ICE, an online and unregulated energy market that then featured these swaps.

Three of Aquila’s managers, each of whom ran a regional trading desk, also subsequently pleaded guilty on criminal charges associated with trades that the indictment said were “routinely” made by the company. The three were sentenced only to probation after they argued at a hearing that the trading activity they were convicted of covering up was directed by higher-ups. One said he wished he “had questioned the legality of Aquila’s practices,” and the lawyer for another said “the methodology had been established by superiors who had been at Aquila for quite some time.”

In addition to these government actions against Aquila, the company paid $10.5 million to settle the class-action lawsuit on behalf of 7,000 of its employees who took a beating stock on Aquila and Enron stock held by their retirement plan, an investment the company did everything it could to encourage. The case charged that Cain’s compensation committee played a particularly strong role in overseeing the push to get employees to invest in Aquila. Also without admitting wrongdoing, the company paid another class of suing investors $1 million to settle a case that charged the board with the failure to appoint an independent audit committee required by law before completing an intricate 2001 exchange of publicly owned stock between Utilicorp and Aquila. Even when Aquila was sold to Great Plains, legal questions were raised by a state overseer when it was revealed that Richard Green quietly met with the Public Service Commission chair before the merger was announced, while Great Plains had done the same with three of the other four commissioners.

Cain was never Aquila’s CEO or chair, so his culpability in the demise of this company is limited. But he certainly did occupy at various times some of its key positions, chairing and serving on critical committees. In companies such as Aquila, where the CEO and chair are the same person, a lead independent director such as Cain is ordinarily charged with presiding at board meetings the chair misses, helping to prepare the agendas for all board sessions, and both calling and presiding at any meetings of the nonmanagement directors. In this position and as chair of compensation, he also authorized the retention of outside advisers. Since Aquila is out of business, it’s difficult to determine how many of these pivotal duties he ever performed. Neither his campaign, nor the Greens, nor Great Plains/Kansas City Power and Light responded to Daily Beast inquiries.

What is clear is that Cain rolled with the speculative explosion that swept Aquila into the energy merchant markets, rewarded the executives who took a once solid power provider into those dicey deals, and stuck with a company even after criminal and civil charges exposed its compromised culture. His track record of acquiescence at Aquila appears to have helped establish him as a reliable “independent director,” a reputation he has turned into a career, earning a fortune on multiple boards since ending his own executive career in the 1990s. Richard Green, who now runs a firm seeking to acquire energy infrastructure assets called Corridor Energy, isn’t still sending maximum donor dollars to Cain without feeling quite comfortable with him. Research assistance was provided by Emily Atkin, Matthew DeLuca, Kelly Knaub, Fausto Giovanny Pinto, and Andy Ross