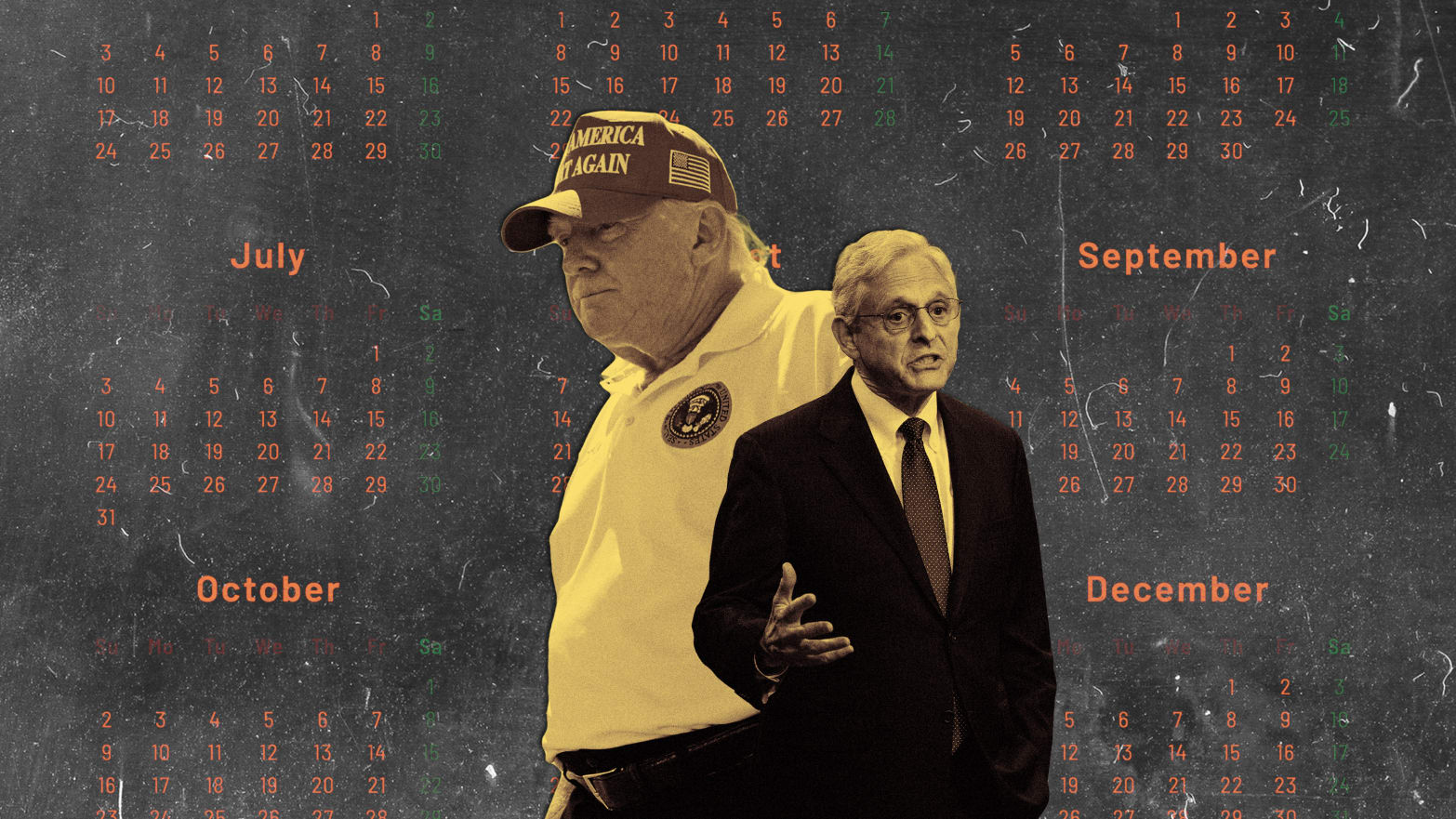

Democrats and Republicans alike were transfixed with the drama of the FBI search of Mar-a-Lago, and many are waiting with bated breath to find out if Trump is in the crosshairs of an imminent indictment.

That’s understandable, given that the question of whether or not the former president will finally pay a legal price for his alleged serial criminality is deeply entwined with the political future of the nation. However, it may be many months—and certainly after the next election—before we learn the full scope of the criminal peril Trump faces, let alone before he is charged.

As we learned during the Mueller investigation, when a criminal law enforcement investigation is conducted appropriately—and in accordance with the governing laws and rules—the public learns very little from the government until (and if) charges are brought or, in rare cases, a report is made public. Indeed, in the case of information adduced from grand jury proceedings, it may well be a crime for government officials to put such material in the public record outside the context of a criminal charge.

Accordingly, while a high-profile investigation proceeds, journalists rely on tidbits coming from government officials who may be breaching their duties of confidentiality. More frequently such leaks originate from witnesses or even targets of the investigation who find it in their interest to disclose certain information. Given the nature of these sources, it should be no surprise that—through no fault of the typically diligent reporters involved—the information we in the public receive is frequently incomplete and, sometimes, even inaccurate.

Furthermore, the information that is disclosed is often received in quite disparate ways by different audiences. During recent months, Trump and his GOP partisans have, predictably, decried the various investigations arising from the events leading up to (and including) the Capitol riot on Jan. 6 as unprecedented “witch hunts” and “authoritarian” overreach, calculated to destroy the ex-president and the party he largely controls.

By contrast, many Democrats were frustrated by the lack of any overt Justice Department focus on Trump himself, with many suggesting—without any evidence—that Attorney General Merrick Garland was cowed by Trump and had made a decision to avoid even investigating his potentially criminal conduct.

Attorney General Merrick Garland delivers a statement at the Department of Justice on Aug. 11, 2022.

Drew Angerer/Getty

Given that political atmosphere, the FBI search of the former president’s Florida residence—which would have been extraordinary under any circumstances—created an even louder thunderclap.

Trump partisans claimed it was confirmation that the FBI (an arm of what Trumpists call the “deep state”) and Garland (now deemed a sinister mastermind) are planning a “legal coup.”

While Democrats are far more fact-based, the search led to much rampant speculation on the left that Trump is finally on the verge of being indicted.

That, however, is likely also wishful thinking.

There are convincing indications that past portrayals of Garland and his prosecutorial team as meek and hesitant to take on Trump and his cronies were far off-base.

The recently disclosed Mar-a-Lago warrant listed specific criminal statutes (including the Espionage Act) the DOJ believes could be implicated by Trump’s purloining of documents on his way out of the White House. It is also now clear that the DOJ’s investigation of crimes that may have occurred following the 2020 election has reached the level of Trump’s White House staff (and other members of his inner circle) and therefore may implicate the former president.

For example, there have been reliable reports that former Trump White House Counsel Pat Cipollone and his top deputy have been interviewed by the FBI; and soon after the Mar-a-Lago search, GOP Rep. Scott Perry of Pennsylvania—who was at the center of Trump’s effort to use the DOJ as a tool for overturning the election—announced the FBI had seized his phone.

It is also highly likely that the FBI and DOJ have obtained documents and information from many other individuals and entities who have chosen to keep their involvement private.

Rep. Scott Perry (R-PA) in 2021.

Ting Shen-Pool/Getty

Well then, you may ask, does that mean that the dam is about to break? Will indictments soon fall like rain, culminating in charges against Trump—whether for his possible hoarding of the nation’s nuclear secrets, or for his efforts to use coercion and violence to undermine the nation’s democracy, or both?

The answer is, almost certainly, no.

First, there is the issue of the DOJ’s longstanding policy against taking so-called “overt investigative steps” in criminal investigations (e.g., warranted searches and grand jury proceedings) that could have political impact close to an election (typically construed as within 90 days). In addition, it was recently reported that AG Garland signed a memo emphasizing that highly politically sensitive investigations require approval from senior DOJ officials.

It is, in fact, more than likely that the timing of the Mar-a-Lago search and the seizure of Perry’s phone were impacted by this policy, since both occurred approximately 90 days before the November elections. The corollary of this observation, however, is that—given the existence of the policy—it is quite unlikely that (absent an emergency) further such “overt” federal law enforcement actions, which could be expected to come to public notice, will occur before the election.

Second, Garland is unlikely to leave the decisions of whether to recommend charges against Trump or his confederates (nor the responsibility for prosecuting them) to his DOJ staff or a U.S. attorney (all of whom are Biden appointees). Instead, he is likely to appoint a special counsel (just as former Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein appointed Mueller). Indeed, the DOJ’s special counsel regulations exist precisely to maintain some degree of distance between political appointees in the DOJ and investigations of political adversaries of the current president or his party.

But, of course, naming a special counsel will itself be an overt step. And should it happen (which looks increasingly inevitable), it will cause a political earthquake that will make the thunderclap of the Mar-a-Lago search seem like a minor summer rain shower. Accordingly, even assuming that Garland’s team has assembled enough evidence to merit the appointment of a special counsel, the AG might decide to wait until after the midterm elections to announce the appointment of the prosecutor who will be charged with overseeing the investigation of the former president.

In the meantime, in the purported name of “transparency,” a wide variety of voices are calling for disclosure of more information about the ongoing investigation. Trump and his GOP partisans are cynically calling for disclosure of more information about the investigation (including the sealed affidavit submitted to the court in support of the FBI’s warrant application)—knowing that such materials won’t be released. The GOP clearly plans to use the necessary secrecy of the criminal investigations as support for Trumpish conspiracy theories.

Local law enforcement officers are seen in front of the home of former President Donald Trump at Mar-A-Lago in Palm Beach, Florida, on Aug. 9, 2022.

Giorgio Viera/AFP via Getty

But it is not only Republicans who are calling for disclosure of confidential information about ongoing law enforcement investigations. Some Democratic members of Congress—many of whom until recently were among the bandwagon of critics accusing Garland of being ineffective—are likewise eager to get details about the nature and scope of the DOJ’s activities.

Garland is strenuously refusing to give into these demands, and for good reason. Disclosing facts about ongoing law enforcement investigations is not only contrary to longstanding policies, it’s sometimes even illegal. Such disclosures can also inevitably risk compromising the success of an investigation, including by tipping off potential subjects, and even indirectly encouraging witness tampering and other acts of obstruction (which, experience shows, Trump has no problem with pursuing).

Of course, the country does have a right to know about potential misconduct involving its elected leaders, particularly conduct pertaining to the electoral process. But we have already seen the danger of using the law enforcement investigative process as a means of vetting and testing candidates.

In 2016, when then-FBI Director James Comey took it upon himself to repeatedly editorialize regarding the non-criminal conduct of Hillary Clinton—right before the election—the consequences were disastrous, to say the least.

So does this mean that the nation needs to cool its heels and remain in the dark about past (and ongoing) threats to our democracy until the properly slow moving law enforcement authorities complete their work? That can’t be the answer, particularly given that we might never learn what the FBI finds out, if those facts don’t lead to criminal charges..

Among the most positive developments during the past year in Washington has been the work of the Jan. 6 committee. Not since the 1973 Senate Watergate committee hearings has a congressional body so effectively presented facts concerning grave presidential misconduct to the nation.

Of course, many Trump partisans don’t believe, or care, about the evidence the committee has presented.

But if overwhelming evidence—presented in public hearings, demonstrating Trump’s attack on democracy—is not sufficient to change the minds of a large minority of Americans, there is no reason to believe that the filing of criminal charges against the former president will suddenly turn them into reform-minded advocates for the renewal of democracy.

Furthermore, there is every reason to have optimism that most Americans have far more open minds, which can be convinced by facts and evidence.

Accordingly, instead of waiting to find out if Trump is going to be charged with a crime, it is the better part of wisdom for Americans to support leaders like the Jan. 6 committee members—especially Rep. Liz Cheney, exiled from her party for telling the truth—who are single-mindedly focused on bringing the important facts to light.