How a Crazy Plan to Rebuild Waco Compound Gave Us Alex Jones

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/Getty

The conspiracy-mongering loon has long poisoned American politics. This is the oft-untold story of how violence, bloodshed, and a right-wing radio rivalry birthed Alex Jones.

Alex Jones is standing next to a heap of concrete slabs. There’s one piece jutting out, to eye-level with his squat frame. Jones puts a hand on it. This is “monument to the wreckage of the police state,” he tells the camera.

“Welcome to the New World Order.”

It’s the year 2000. Seven years earlier, on the exact spot where Jones is ranting to camera, federal agents moved in on the Mount Carmel Center. Inside were 100 members of the Branch Davidian cult. The results were a disaster.

The Branch Davidians, led by their prophet David Koresh, swore they would not be taken alive, and they lived up to the promise: 82 members of the sect died during the standoff and ensuing raid.

Jones, who was until recently a marginal and out-of-work radio host in Austin, was visiting the former site of the compound, just outside of Waco, Texas to shoot a documentary for his fledgling online media network.

From behind black sunglasses, he nods to the industrial carnage: “They always destroy the evidence and don’t let locals in to document anything. What do they have to hide?”

The shaky camera cuts to Jones making a beeline across the field, with more wreckage in the background. The camera pans over to another film crew. Jones marches up to them and starts getting into it: “I’m sick and tired of hearing your lies, when you machine-gunned a bunch of men, women, and children,” he’s screaming. “You’ve got a big problem, buddy.”

As Jones gets closer to the man in front of the camera—a reporter for CBS—the lower-third of the screen offers a helpful, if misleading, title for the journalist: “FBI AGENT.”

The reporter nods, smirking, as Jones lays into him. “A revolution of peaceful information is coming. And when it comes time, you people are going to be brought to punishment,” Jones says, thrusting a finger towards the reporter.

Jones had another reason for being in Waco: He was leading a charge to rebuild the Branch Davidian compound from the ground-up. In the process, he would wind up building up a whole new conspiracy empire.

An air raid siren sounds. A deep baritone voice punches through the anxiety-inducing wall of sound: “Lights out on the hour, it is the hour of the time.” Dogs are barking. People are screaming, jackboots hit the ground. These are the palpable sounds of the end of the world.

For eight years, that’s how William Cooper began his radio program.

Cooper’s name is largely forgotten these days, but he stands as one of the most influential shortwave radio broadcasters and conspiracy theorists in modern America.

In his own accounting of his life, Cooper’s formative moment came when he was serving in the Navy, aboard the submarine USS Tiru. Cooped claims to have seen a massive, disc-shaped UFO emerging from the ocean and submerging again. His superiors, he would later write, told him to never speak of it again.

He would go on to serve two tours in Vietnam. After which, Cooper claimed to have been upgraded to have been given the security classification of “Top Secret, Q, Sensitive Compartmentalized Information with access authorized on a strict need-to-know basis.” (Q clearance is issued by the Department of Energy.) Cooper claimed that the same day he received that classification, he saw records proving the Navy and Secret Service had assassinated President John F. Kennedy. That sent him down the rabbit hole.

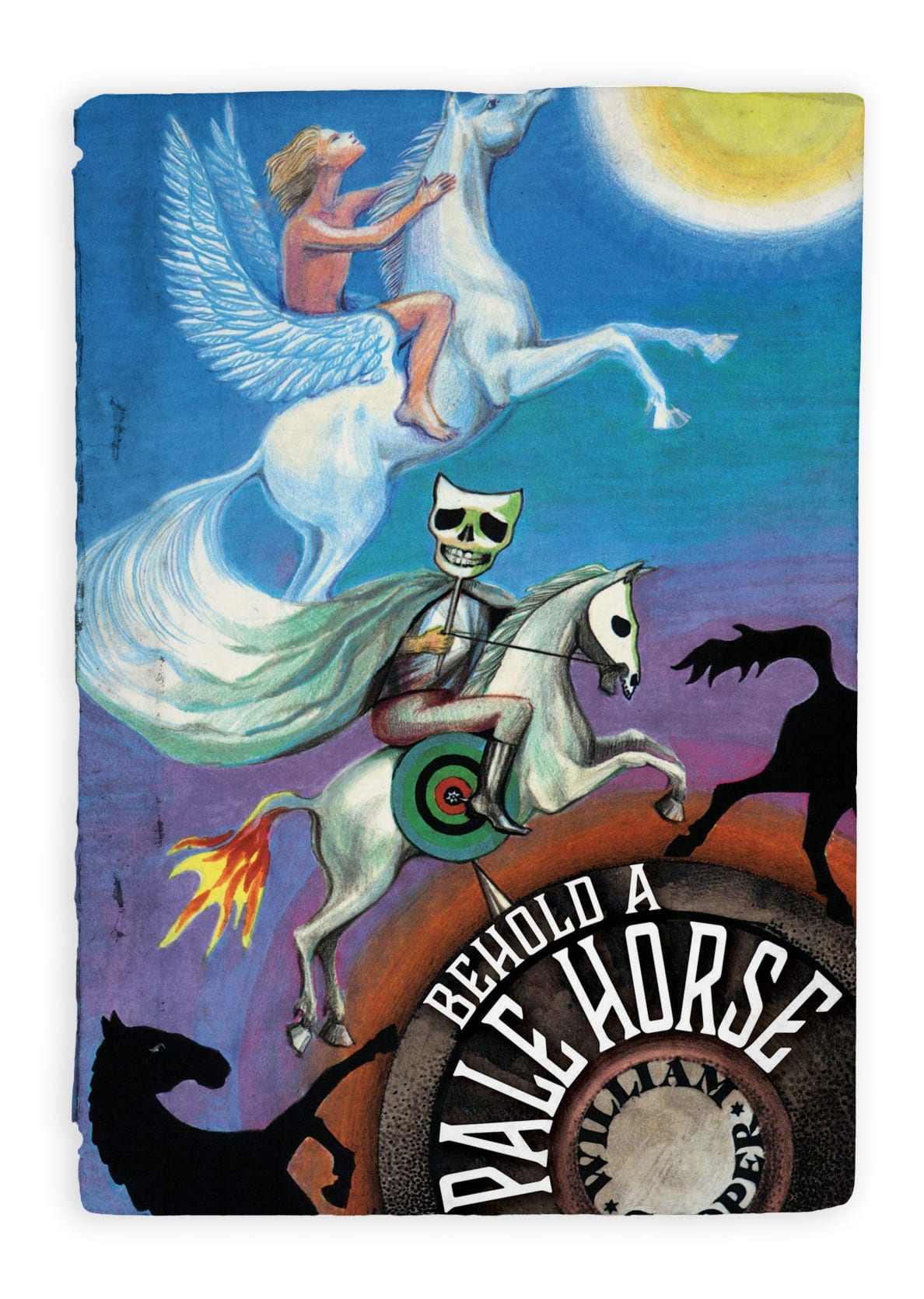

“I have found evidence that the secret societies were planning as far back as 1917 to invent an artificial threat from outer space in order to bring humanity together in a one-world government which they call the New World Order,” Cooper wrote in his seminal 1991 book, Behold a Pale Horse. “I am still searching for the truth.”

Cooper claims that the government tried, twice, to kill him for his whistleblowing.

Behold a Pale Horse is perhaps the most popular, and all-encompassing, conspiracy manifesto ever published. In it, Cooper claims the Illuminati, Rothschild family, Bilderberg Group, CIA, Pope, United Nations, Communist Party, Nazi Party, Skull & Bones, Bohemian Club, and a raft of others were responsible for this Satanic globalist plot. A secret deep state, operating in the shadows.

Some of this theorizing was old hat, at this point. A French minister had accused the secret society of secretly plotting all manner of world events, including the Reign of Terror, which begat an anti-Illuminati panic in America in the eighteenth century. Through the Cold War, the arch-conservative John Birch Society warned that America had already fallen prey to a one world socialist government, and that its “tentacles now reach into all of the legislative halls, all of the union labor meetings, a majority of the religious gatherings, and most of the schools of the whole world.”

Cooper’s 1991 book, Behold a Pale Horse.

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast

Whether it was crypto-Catholics or Communists, these tall tales warned the enemy was lurking somewhere in the shadows—or, perhaps, in the rival political party. What made Cooper’s conspiracy theories so terrifying is that he pointed a long finger at the face of the conspiracy: The U.S. government.

For Cooper, all politics was corrupted by these secret societies. “The important fact to remember is that the leaders of both the right and the left are a small, hard core of men who have been and still are Illuminists or members of the Brotherhood. They may have been or may be members of the Christian or Jewish religions, but that is only to further their own ends. They are and always have been Luciferian and internationalist.”

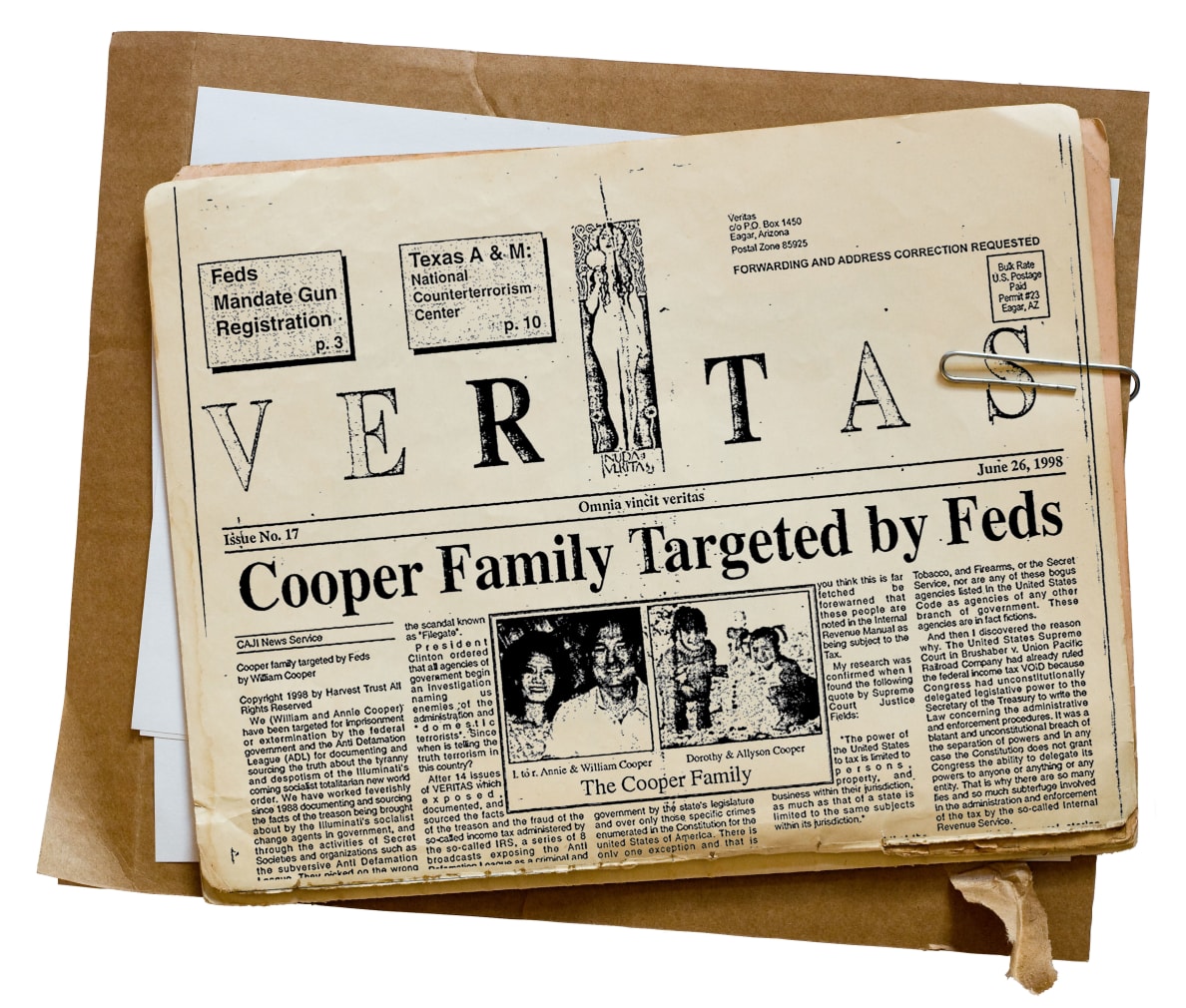

Cooper, at this point, was living on a compound in Arizona with his wife and daughter. He attempted to wall himself off from society: He stopped paying federal income tax, deeming it unconstitutional. He was heavily armed, and didn’t like unexpected visitors. He didn’t trust anyone, or anything—except radio.

“The only really open media left to the public is talk radio,” he wrote.

From his outpost in the Arizona White Mountains, Cooper put together a makeshift radio station. Shortwave radio allowed even amateur and independent broadcasters to blast a signal across huge distances—with help from Nashville-based WWCR, Cooper’s transmissions could reach as far away as Europe.

At least five nights a week, he walked listeners through his deeply paranoid philosophy in his slow drawl. He warned of the coming one world government. He tied every major news story back to this shadowy cabal of puppet masters. He castigated the “vast herd of American sheeple” who had not yet followed him down the rabbit hole.

It was shockingly effective. He would claim a listenership of millions, maybe even tens of millions, worldwide. (Mark Jacobson, author of Pale Horse Rider: William Cooper, the Rise of Conspiracy, and the Fall of Trust in America, says the listenership was more likely in the tens of thousands.) He fit into a growing, loose-knit, movement of anti-government militias which had started to emerge across America. He even founded his own, grassroots, spy agency: The Citizens Agency for Joint Intelligence. Members were encouraged to collect intelligence and send it to Cooper to be synthesized and interpreted for broadcast.

His emerging prominence led to an explosion of popularity for his book: It would later be approvingly cited by a number of hip-hop heavyweights including Tupac Shakur, influence multiple episodes of the X-Files, and earn status as one of the most-shoplifted books from Barnes & Noble.

Cooper had only been on the air for a couple of months when, in February 1993, hundreds of agents from the Bureau of Alcohol, Firearms, and Tobacco raided the Branch Davidian compound in Waco. The ATF had reason to believe that the Branch Davidians had stockpiled a variety of assault rifles and machine guns. There were suspicions—later proven correct—that cult leader David Koresh had married underaged members of his sect. When officers arrived to execute the warrant, a firefight erupted: Four federal agents and six Branch Davidians were killed.

After that deadly interaction, the federal agents pulled back. For weeks, they sat outside the Mount Carmel Centre in an uneasy standoff.

Cooper had repeated to his listeners that crises and strife would occur when the deep state wished it so—whether it was the World Trade Center bombing or the invasion of Yugoslavia, Cooper insisted, it was all part of the plan. “I remain the most accurate predictor of future world events in the history of the world,” he told listeners.

The Hour of the Time turned its attention to the events in Waco on March 30, just as the standoff was growing increasingly tense. Agents from the FBI and other law enforcement agencies had joined the ATF, bringing with them tanks and a considerable amount of firepower. Inside, Koresh and the Branch Davidians manned dozens of illegal machine guns.

“They are fighting for their creator-endowed rights. They have committed no crimes. They know what the sound of battle is. They know what it’s like to see their friends or relatives die in their arms or at their feet. They know what it’s like to have wounded and be refused medicine and medical treatment,” Cooper said. “Oh, yes, we are at war. Make no mistake about it.”

The FBI hatched a plan to throw tear gas into the compound, in hopes of smoking out the Branch Davidians—a plan the FBI communicated to the sect. When a tank breached the walls to create an opening for the gas canisters, the Branch Davidians opened fire. With that, the federal agents moved in: The battle began. As both sides engaged, some Branch Davidians began setting fires within the compound. Over the next six hours, dozens of members of the church died from the fire, smoke inhalation, or from gunshot wounds.

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast/Getty

In total, 76 members of the sect would die in the raid: Most by suicide, or by the hands of their fellow Branch Davidians.

“The second part of the second American Revolution has come to an end,” Cooper told his listeners in the days after the siege. “Folks, we lost. And you’re next.”

Cooper would obsess over Waco in the weeks, months, and years to come. The Hour of the Time became a core vector for the misinformation that would plague the story for years—that the FBI had set the fires, that the federal agents denied medical care, that ATF agents had executed the Branch Davidians, that the media had been tipped off about the planned raid. His DIY intelligence service supplied flimsy evidence for his grandiose claims. In one interview with attorney Linda Thompson, who had become one of the loudest voices for the Waco conspiracy, she explained Washington had planned “a big massacre” from the beginning.

“How many more people are you going to allow to be jailed, persecuted, burned to death, murdered—because you are a coward,” Cooper hectored his listeners. “That’s basically what it boils down to, isn’t it? Cowardice.”

Listeners to Cooper’s show were three men who would become legends in the American far-right: Terry Nichols, Timothy McVeigh, and Alex Jones.

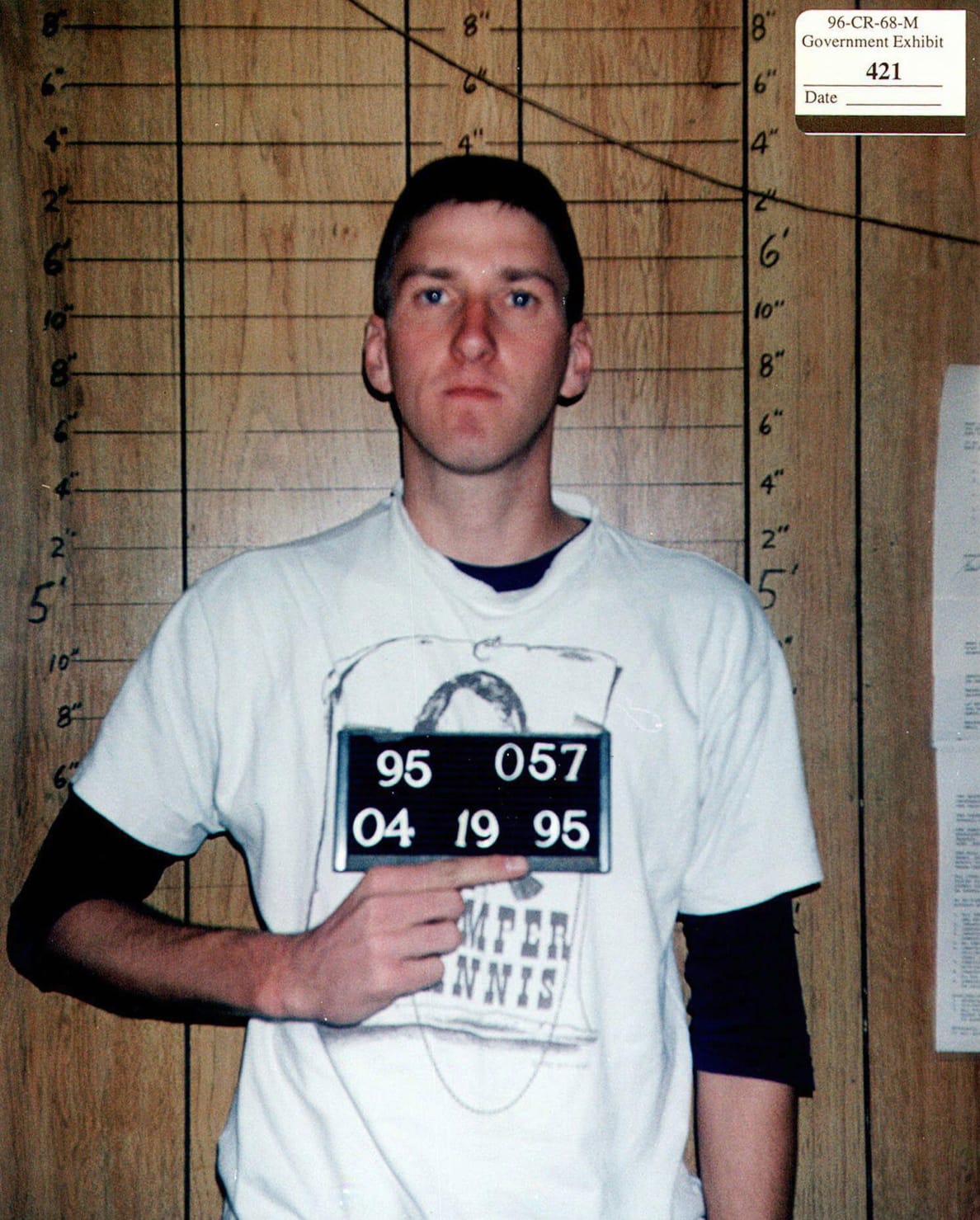

Timothy McVeigh came back from Operation Desert Storm a paranoid, angry man.

At gun shows, McVeigh was selling copies of The Turner Diaries—a novel about sparking a race war to overthrow the corrupt Jewish-controlled state, a book which has become a bible for extremist right-wing movements. He bought a membership in the Ku Klux Klan. He planned to wear the KKK-made “white power” t-shirt around his military base.

McVeigh would receive an honorable discharge from the military, just as he descended further into madness. He spent his time travelling to gun shows during the day and listening to shortwave radio by night.

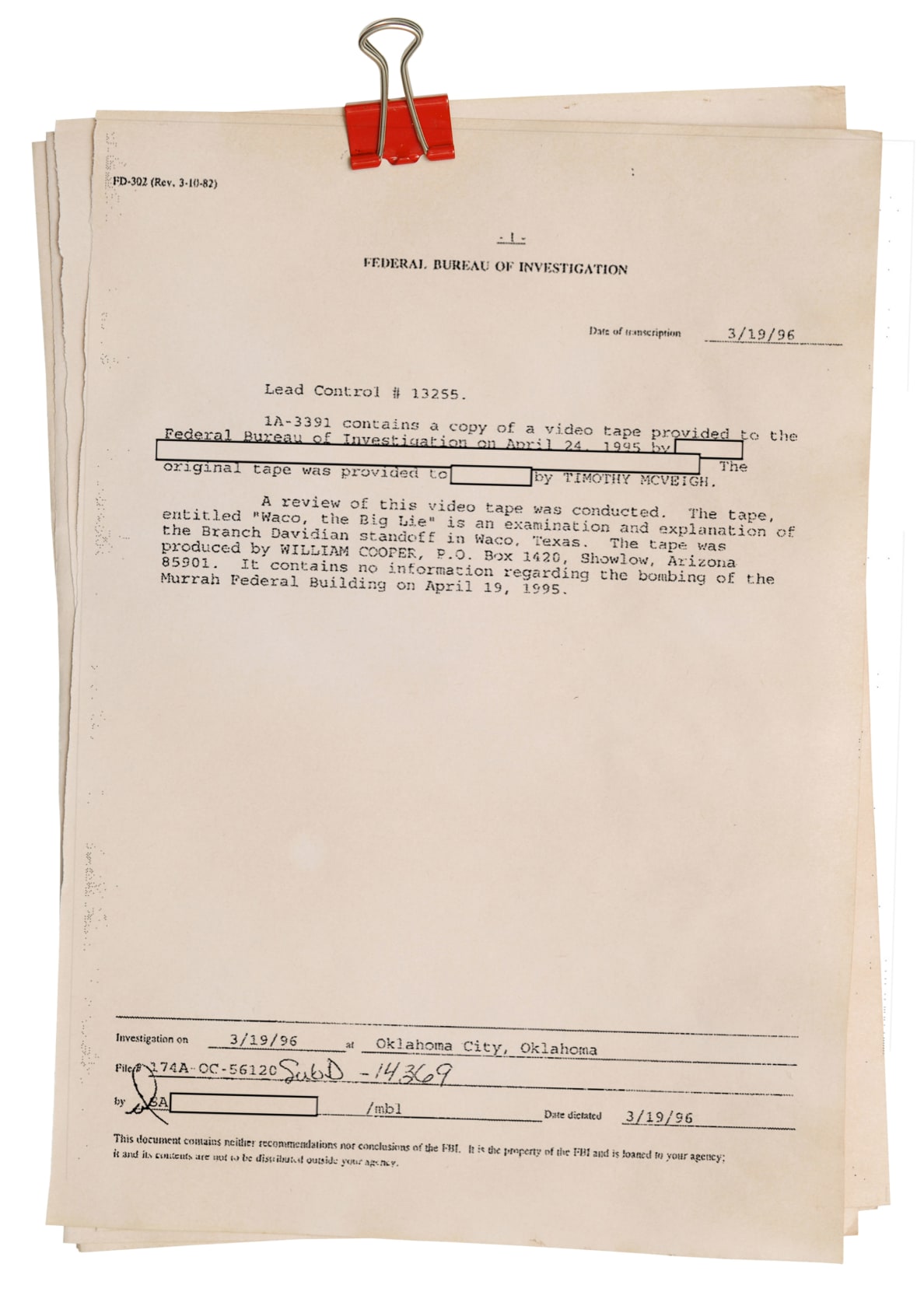

In early 1993, McVeigh drove to Waco to witness the standoff. After being denied entry to the Mount Carmel centre itself, he parked just outside the cordon of federal officers. He hawked bumper stickers he had made up: “FEAR THE GOVERNMENT THAT FEARS YOUR GUNS,” read one; “A MAN WITH A GUN IS A CITIZEN, A MAN WITHOUT A GUN IS A SUBJECT,” read another.

McVeigh left Waco before the agents moved in, afterwards he sent off for a mail-order tape from William Cooper: “Waco, The Big Lie,” which Linda Thompson had produced and Cooper was marketing. He became obsessed with the idea that the U.S. government was out to destroy American patriots, just like Cooper had warned.

Timothy McVeigh

FBI Handout

The Iraq veteran “developed a kind of evangelical zeal to spread the message about Waco, lest the enormity of the government’s actions diminish over time,” write Dan Herbeck and Lou Michel in American Terrorist: Timothy McVeigh & The Oklahoma City Bombing.

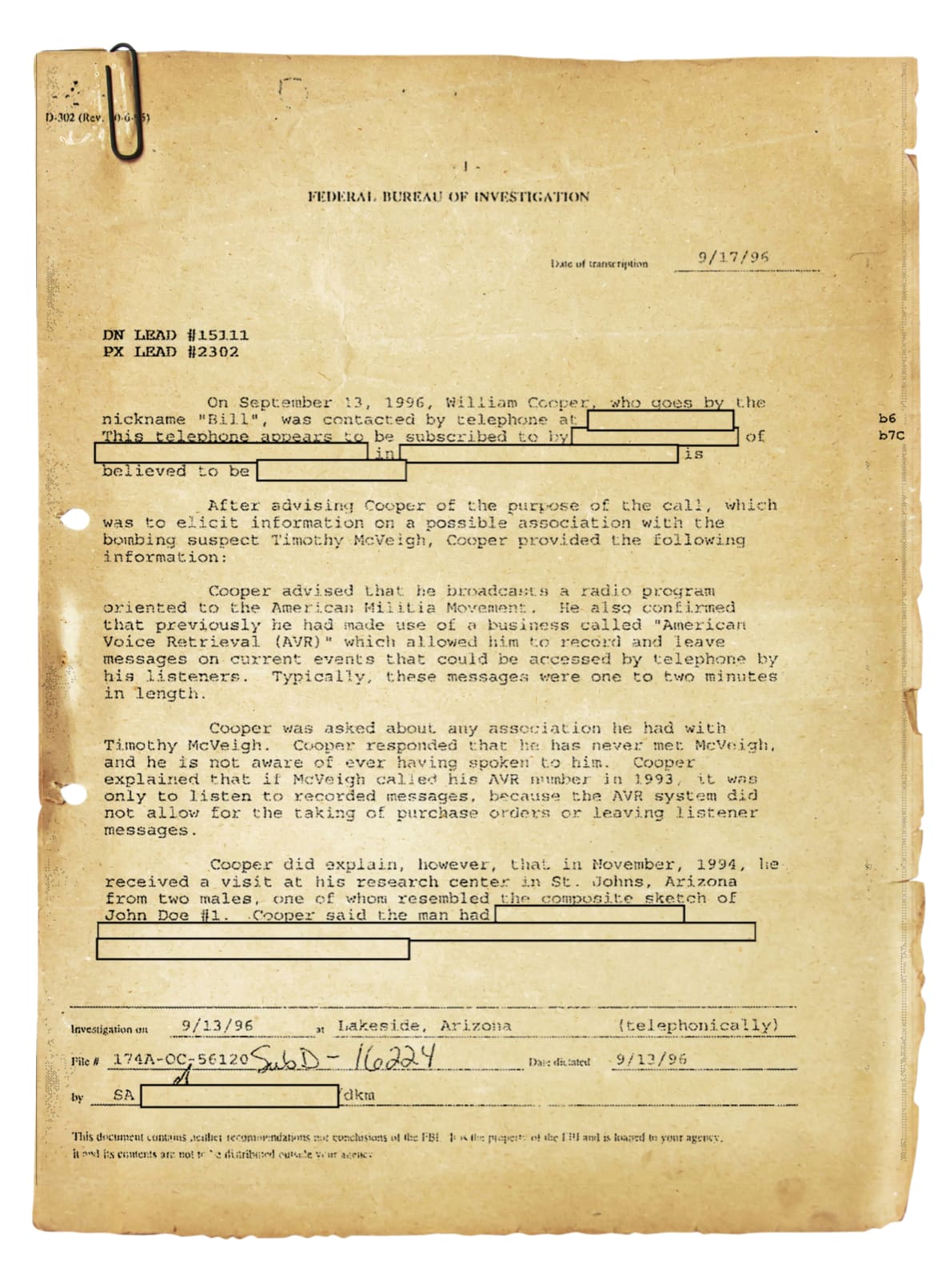

According to the FBI, two men matching the description of McVeigh and Terry Nichols, his former roommate, visited Cooper’s compound in November 1994. Cooper told the Bureau that he “received a visit at his research center, in St. Johns Arizona, from two males” who were “interested in his philosophical and political messages, but they disagreed with him on his methods.” Cooper rejected violence and, per his own recounting, told them he wanted nothing to do with whatever they were planning.

As they left, one handed Cooper a copy of The Turner Diaries. Cooper, again per his own recounting, told them he already had a copy of “that racist book.” Not just racist, the book also glowingly depicts how the band of white resistance fighters spark the race war by parking an explosive-laden truck outside a federal building.

They left the copy of the book anyway, and an invitation—maybe a warning—to “watch Oklahoma.”

It’s impossible to know for sure if either of those two men were McVeigh and Nichols, but the FBI certainly spent considerable time pursuing that possibility. Their warning to keep an eye on Oklahoma City was certainly prescient: Five months later, at 4 a.m, the alarm on McVeigh’s shortwave radio went off. He leapt out of bed, got in the cab of the truck, and drove to a storage unit in small-town Kansas where he and Nichols loaded fertilizer into the back and began mixing the nitromethane. From there, they headed to Oklahoma City.

The next morning, McVeigh parked the truck outside of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City and lit the fuse. It was April 19, 1995.

It was an auspicious anniversary that not everyone appreciated. William Cooper certainly did.

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast/Getty

“Today is the second anniversary of the Waco massacre, so I don’t want anyone out there to forget it, ever,” The Hour of the Time began that evening. “A thousand years from now, I want patriots somewhere—I mean patriots to principles and ideals of liberty and freedom—to remember the Waco massacre.”

But, he noted, “it appears that someone is using this anniversary to promote an agenda.”

That morning, 168 people had died in the worst domestic terror attack to ever occur on American soil. McVeigh’s bomb had been parked just outside the building’s daycare center. McVeigh and Nichols would be arrested and charged in the hours and days after the attacks.

The FBI would investigate Cooper’s role in influencing the deranged ideology which had spurred the bombing, but would lay no charges.

Police found pages from the The Turner Diaries in McVeigh’s getaway car.

Alex Jones got his start in the low-budget world of public access television in Austin, Texas.

Public access is an interesting beast: A place where there are no real rules, and the stakes are impossibly low. That’s where Jones’ first test drove his anti-government shtick—it was simultaneously as paranoid and conspiratorial as Cooper’s shortwave broadcasts, but wrapped in a more entertaining package.

Jones was only 19 when the siege at Waco occurred. When he first began broadcasting—first, on TV, then as a full-time talk radio host on station KJFK—he was barely legal to drink.

Between radio and television, Jones had amassed a small cult fandom. In 1997, readers of the alt-weekly Austin Chronicle voted Jones “best looking crank.”

“He does seem to be an impressionable young lad,” the newspaper wrote. “But Jones’ heart always seems to be in the right place, expressing outrage at the dominant media and the Clinton administration and whatever other windmill he can topple.” It’s impossible to say what portion of his fans were drinking the kool-aid, and how many were just bemused at his antics.

“His nicely chiseled features contort shockingly into all sorts of configurations to accent his disdain and chagrin,” the Chronicle continued. “It’s kinda fun to watch. And damn, he is cute.”

Jones’ radio show, in particular, cribbed much of Cooper’s fears of a New World Order. Of a secret shadow government. In particular, he fixated on the secret banking cartel that actually ran the global financial system.

In 1998, three years after the Oklahoma City bombing, Jones cut off a conversation with one of his listeners—a buddy, he admits—about a black helicopter hovering over his home. His guest had just called in. “What’s going on, Mr. Cooper?” Jones said with his particular Texas twang.

Like most of his interviews, Jones approached the conversation with William Cooper as an excuse to hear himself talk.

“We get followed around by unmarked police cars, openly taking 35 millimeter photographs of us,” Jones ranted. “That’s just wonderful, isn’t it?”

Deadpan, Cooper responded: “Well, it’s just one other manifestation of the Nazi Gestapo police state which is taking over this country.”

At this point, Cooper’s anti-government paranoia had evolved into full-fledged hostility to the American state. He had met with FBI investigators over the Oklahoma City bombing, but was less than helpful when they asked for the copy of The Turner Diaries that the mysterious duo had given him. His refusal to pay income tax had started to become a problem. Whenever the U.S. Marshals tried to summon Cooper to court, he threw them off his land. When an FBI agent visited the compound, he found three guard dogs tied to cars and a man with a “military-type haircut” and a pistol on his hip. Federal officers would opt to leave Cooper alone, preferring to avert the possibility of another Waco over the need to subject the broadcaster to the tax regime.

It was precisely that infamy that led to Jones’ fawning adoration.

Jones summed up what the newspapers were saying about Cooper: “Arizona militia man, tax fraud and bank fraud: He’s refusing to come into the loving arms of [then-Attorney General] Janet Reno.”

Cooper chuckled, clearly bemused by Jones’ fawning. “I am not a tax fraud or a tax cheat. I pay all legal, lawful and constitutional taxes, which I am required to pay.” (Cooper believed the federal income tax to be illegal.) But, he warned: “Not only will I not come in, but if the civil war has to start right here, it will.”

Jones ranted about all the enemies who stood against patriots like he and Cooper: Hollywood, the media, universities, the banking system, “all their whores and all their pawns and all their little agents don't mean a damn to you,” Jones said. “And if the feds tried to come and take your home and take your family, that you're going to oppose them with force of arms.”

Cooper responded: “Absolutely.”

By the late 1990s, right-wing radio had ascended as arguably the most important vehicle for political media in America. At the helm was Rush Limbaugh. He had just delivered Newt Gringrich control of both houses of Congress. Dozens, if not hundreds, of Limbaugh wannabes were cropping up across the country, looking to put his stamp of politically incorrect conservatism onto their local airwaves—and to make some money doing it. (My podcast, titled The Flamethrowers, delves deep into how that movement helped create the deeply partisan and paranoid political culture that runs rampant in America today.)

But Oklahoma City laid bare how the proliferation of right-wing radio had fostered the growth of a media culture more paranoid and dangerous than what you might hear on WABC, Limbaugh’s New York station. This new culture of hard-right, anti-government, illberal talk was directly contributing to the radicalization of disaffected young men. The refrain that America had been taken over by a cabal of secret societies, hell-bent on enslaving the American people under a one world socialist government, was certainly a powerful one.

Cooper was king of this corner of the market, and Jones was just a pretender to the throne.

After the bombings, President Bill Clinton challenged those broadcasters head-on. “We hear so many loud and angry voices in America today whose sole goal seems to be to try to keep some people as paranoid as possible and the rest of us all torn up and upset with each other,” Clinton said in the week after the attack. “They spread hate. They leave the impression that, by their very words, that violence is acceptable.”

While he emphasized their right to say it, an incredulous Clinton seemed to be directly challenging Cooper: “You ought to see—I’m sure you are now seeing the reports of—some things that are regularly said over the airwaves in America today.”

Some, like Limbaugh, took those comments as an affront. “There is absolutely no connection between these nuts and mainstream conservatism in America today,” Limbaugh said. (While that was partly true, Limbaugh was particularly responsible for pushing the conspiracy theory that the Clinton family had White House counsel Vince Foster murdered—a belief that continues to the present day.)

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast/Getty

Others had taken Oklahoma City as a wake-up call.

The most famous is probably Art Bell, who broadcast "from the High Desert and the Great American Southwest,” as he explained in the opening of his nightly show.

Like Cooper, Bell broadcast from his own desert compound—his, situated between Death Valley and Las Vegas. And, like Cooper, he spent the early 1990s fixated on the intersection between aliens, America, and a looming socialist one-world government. Before the 1995 attacks, Art Bell was warning his listeners that the “murder” at Waco was all about the mass-confiscation of American firearms.

But Bell would later write in his autobiography that when he learned the bombing was retaliation for Waco, it “scared the hell out of me.” From that point on, Bell ditched the paranoia over the new world order and, instead, dedicated himself to trying to uncover hidden truths and the secrets that hide in the shadows: From the paranormal to the extraterrestrial. In so doing, he largely ditched fears of gun confiscation. His show, Coast to Coast AM, would become a cult classic.

Others took the opposite lesson from the bombing. Jones doubled down after the attacks. He didn’t believe that Oklahoma City was, in fact, carried out by two men who identified with the militia movement and broadcasters like Cooper. He saw the deep state’s hands on everything. He was, like his idol, an ideologue. He wasn’t on the airwaves to make money, gain fans, or crack jokes.

In his conversation with Cooper, he lamented how taxing it was to host his program six days a week and fail to make any headway. “I’m 24 years old,” he ranted, his voice rising. “I may just say ’screw it!’ Because you got these people cramming cheeseburgers in their mouth and they love it.”

Cooper, in his even-temper drawl, agreed. “Of course it does. What angers me most is the stupidity of the vast herd of American sheeple out there that think they know something and they don’t even know what planet they’re on, to tell you the truth.”

In 1998, Jones’ page on the KJFK website advertises how Jones “categorizes the undermining of our national sovereignty, probes into the destruction of the federal building in Oklahoma City, explores the undermining of national security, and exposes international organizations such as the United Nations and the Council on Foreign Relations.”

As was fairly customary in that naive era of the early World Wide Web, there is a section for “Alex’s favorite links!”

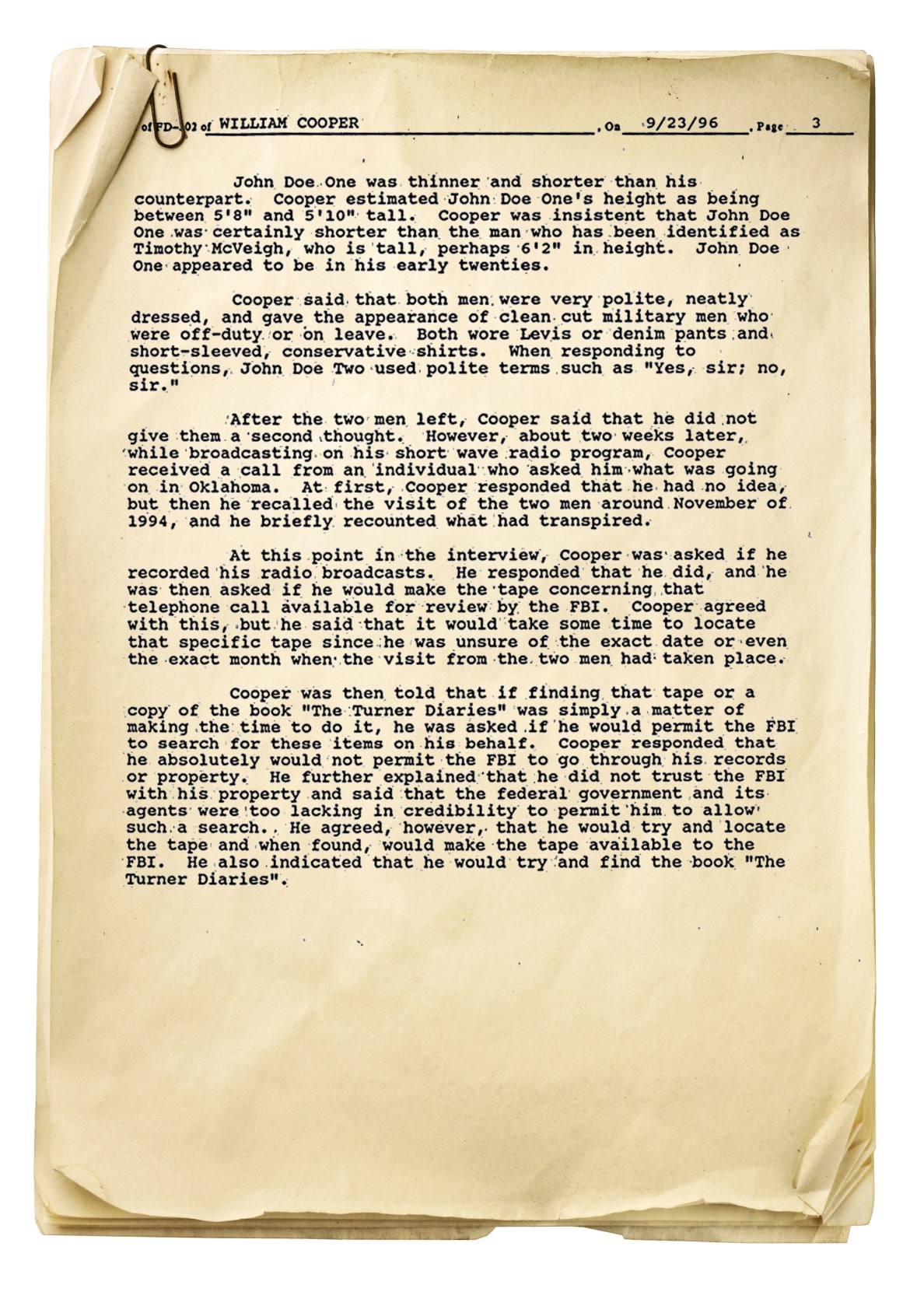

526765052

The Branch Davidians' Mount Carmel compound outside of Waco, Texas, burns to the ground during the 1993 raid by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF).

Greg Smith/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty

The third was labelled “Waco holocaust museum.” It links to a website run by Linda Thompson, who produced the documentary McVeigh had ordered not long before the bombing.

The website is still live. It is testament to the belief that Waco was actually a government plot to suppress law-abiding Christians. That any investigation which put blame onto the Branch Davidians was “psychological warfare,” and that the Oklahoma City bombing was “a joint attempt by government and news services to discredit all persons of conscience who protested the Waco Holocaust.”

You have to visit an archived version, from 1998, to see the links to Cooper’s website and to the page of notorious holocaust denier Ernst Zundel—which asks “Did Six Million Really Die?"

If the terror attack in Oklahoma City was, like these broadcasters insisted, a false flag operation, they were going to have to come up with their own to make Americans remember Waco.

“All of it—it’s all about public opinion,” Jones told the Associated Press in 1999.

The news wire was visiting the former site of the Mount Carmel Center. Jones had led dozens of volunteers there, just outside Waco, to help rebuild the church.

Swinging a pickaxe was Clive Doyle, the Branch Davidian leading the charge—both his daughters were underage brides of Koresh. His youngest daughter, Shari, died in the fire. Despite his family’s loss, Doyle, one of the few male members of the sect not to face jail time, was still committed to their religious mission. And Jones was his hype man.

The conspiracy broadcaster had raised $92,000 in order to rebuild the church, a level of success that even earned him a spot in Tonight Show host Jay Leno’s monologue. (“Use concrete this time,” Leno advised.)

Jones’ work had finally crossed a line with his station: He was fired from the airwaves just before the millennium. But it turned out to be exactly what Jones needed: He went independent. He registered his own website, at infowars.com. Within a matter of weeks, his new show had been picked up by Genesis Communications Network and syndicated to 60 cities across America. He used the new network to promote his rebuilding efforts in Waco.

At 25 years old, the best-looking crank in Austin had gone national.

A new Branch Davidian church was raised just in time for the seven-year anniversary of the raid in 2000. The church bells rang out 82 times, for each member of the sect killed. The congregants who returned to the site were not as fanatical or fatalistic as Koresh: The original leadership of the church, who had been forced out by the self-styled messiah, took control once more.

Jones had used the effort to give himself a massive new national profile and he hadn’t planned on squandering it. He shot a new documentary on the site, calling it America Wake Up or Waco.

His idol, however, hadn’t joined the push to rebuild the Mount Carmel Centre. William Cooper was a lone wolf, and preferred to stick around his property in Arizona—in some small part, perhaps, because he risked arrest if he left.

As Infowars gained national notoriety, Cooper soured on Jones in a big way. On his show in January 2000, Cooper would address the Infowars host personally: “Alex Jones, you are a bald-face, miserable, stinking little coward, liar.” To make sure he got his point across, Cooper repeated the insults again.

Cooper was, in fairness, right. Just weeks before, on New Year’s Eve, Jones had breathlessly reported that recently-installed Russian President Vladimir Putin had launched a barrage of nuclear missiles. He frantically warned that American nuclear plants were about to melt down. He warned that FEMA and the military were preparing for some kind of massive operation.

1027066478

Alex Jones speaks to members of the media outside a Senate Intelligence Committee hearing in Washington, D.C. on September 5, 2018.

Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty

Cooper was many things—an anti-semite, a racist, a dangerous loon—but he did draw the line somewhere. “The lies and the deceit and the rumors that he spreads over the airwaves that are not good for any of us, and they’re not good for the nation. They are especially not good for militias and patriots,” Cooper continued, blaming Jones for “panicking millions of people, who were putting their children and their belongings in their cars and heading for the hills.”

There was some jealousy at play. Jones was certainly doing Cooper better than Cooper could do Cooper. (The Hour of the Time would also spend considerable amounts of time attacking the increasingly popular Art Bell, as a proponent of the New World Order.)

It didn’t matter if Jones insisted that Oklahoma City had been an inside job, that he helped to rebuild a cult compound in Texas, or that he warned his listeners of a world war that never occured—he had mastered how to mix distrust with credulity. He convinced his listeners that he, and only he, could be trusted. No matter how much evidence sat behind the official version, nor how absurd his explanations became, he was in the right and the state was lying. It was a dizzyingly powerful skill.

In 2000, Jones produced a documentary called Dark Secrets Inside Bohemian Grove. In it, he cribbed Cooper’s fantastical ramblings about secret societies and boiled it down into something snappy and compelling. Where Cooper preferred to lay out the secret order of the world from his compound in Arizona, Jones believed in getting into the field.

The documentary honed in on one of Cooper’s oft-cited secret societies: The Bohemian Club. Every year, the club threw a party in a private park in Sonoma County, California—it treated politicians and captains of industry to much of the esoteric pageantry of Yale University’s Skull & Bones society.

Jones spun a fantastical tale, insisting that the meeting of powerful men inside the park was not just a silly getaway, but a planning event for the New World Order. (Harry Shearer, who attended the party at the Grove once, remarked to documentarian Jon Ronson, “if they were really serious about the task of running the world in secret conspiracy I don’t think they’d be doing so much drag.”)

As a shaky, grainy camera shot narrowed in on the gathering, from a vantage point across the lake, Jones explained that the true purpose of the Bohemian Grove was about child sacrifice. These powerful men burned their human tribute at the foot of a giant wood owl.

Towards the end of the documentary, Jones stands with a bullhorn across the street from the Texas capitol building, screaming that then-governor George W. Bush was a “Luciferian twit.” Jones was convinced that every member of the Bush family had also been a patron of the Bohemian Grove. “You might think you can feed on the human population: We say no to you!”

Just as McVeigh took Cooper’s command to ensure America never forgets Waco, one of Jones’ listeners leapt into action after watching the documentary.

In mid-2001, ex-Marine Richard McCaslin got into costume. A cosplayer who considered himself a real-life superhero, McCaslin had adopted the persona of the Phantom Patriot. As a promo video he produced for his character warned: “New world order, cower in fear. Your globalist agenda will soon be made clear. The Constitution stands as our source of power. The truth, in its words, will win the final hour.”

McCaslin genuinely believed Jones when he said the Bohemian Grove engaged in child sacrifice. And he believed it was his duty as a real-life superhero to act.

In early 2002, McCaslin raided the park, equipped with a pump-action shotgun/rifle hybrid, a .45-caliber handgun, a crossbow, and a sword. He had plans to save any children being kept at the camp or, at least, to burn down the shrine at which they were sacrifice. But upon breaking in, McCaslin found the park deserted.

After spending the night in the park, and trying to burn down part of the camp, McCaslin was arrested without violence. He was convicted on a slew of arson and firearms charges, and spent six years in prison.

“I found out the hard way that if you use extreme tactics to expose the pedophiles and murderers of the Bohemian Club like George Bush Senior and Dick Cheney you will get locked up,” McCaslin said in a video uploaded to his YouTube page after his release.

Tea Krulos, who would interview McCaslin extensively after his release for his book American Madness, wrote that conspiracy theorists, Jones in particular, bear responsibility for McCaslin’s radicalization, writing: "The rabbit hole is a plunge that some people never escape from."

The aftermath of the raid on Waco, even more than the events themselves, would fundamentally change American politics for decades. We’re still feeling the effects today.

William Cooper became a voice for the thousands, if not millions, of Americans who feared that the jackboot of the state was lowering onto their neck. He prophesied a civil war, and held up Waco as the opening battle. After the fires subsided, he called on his listeners to never forget the events that happened at the Mount Carmel Center: And Timothy McVeigh heeded the call.

For years afterwards, Cooper continued sermonizing for legions of militia members, sovereign citizens, conspiracy theorists, and extremists. In September 2001, as planes felled the twin towers, slammed into the Pentagon, and crashed in rural Pennsylvania, Cooper spent 10 hours on the air.

In that wreckage, Cooper saw the saw clues as he did in 1995.

“What happened to the World Trade Center towers today is exactly what happened in Oklahoma City,” he said. “It wasn’t that truck parked up on the street that brought the building down, and I can’t bring down a building like that by flying a plane into the top quarter of it.”

That conspiracy theory would become prolific. In 2006, one pollster found that more than 15 percent of Americans thought it very or somewhat likely that explosives brought down the Twin Towers, not planes.

Other aspects of Cooper’s deluded worldview have lived on in even bigger ways. The tenets of his conspiratorial dogma are everywhere in the QAnon conspiracy movement: From his core belief that the plot to assassinate John F. Kennedy was an inside job, to his allegation that a secretive deep state of Luciferian secret societies secretly run the world.

But Cooper’s story stops short just two months after the events of 9/11. On Nov. 5, 2001, sheriff’s deputies arrived at Cooper’s compound to arrest him on assault and weapons charges—while federal agents gave Cooper a wide berth, it was the local sheriff’s department that deemed Cooper a threat to the community. In recent months, an armed Cooper had taken to confronting anyone who even approached his property.

When the officers arrived, a gun battle ensued. Cooper shot one officer in the head. The officers shot Cooper six times, killing him.

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast/Getty

Jones’ career, of course, took an entirely different trajectory. Like Cooper, he took to the air on 9/11.

“I believe from all of the evidence before us that I’m about to cover, either the government actually carried out this bombing themselves—the new world order occupational government—to create the crisis, to offer the solution… or ladies and gentlemen they allowed terrorists to engage in this sinister activity,” he began in the days after 9/11. “We’ve proven Oklahoma City was a government terrorist bombing.” This was no different, he ranted.

Jones rode the wave of 9/11 conspiracy theories for years to come. Infowars has become one of the most important hubs for misinformation, conspiracy theory, and far-right hate in the world. Jones used that platform to boost then-candidate Donald Trump in 2015—Trump, in turn, told Jones “Your reputation is amazing.”

Jones also used that stage to give the Pizzagate conspiracy theory its first major public endorsement, effectively birthing the QAnon movement. Less than a month later, Edgar Welch would carry his AR-15 into the Comet Ping Pong pizzeria in Washington, D.C, looking to save child sacrifice victims—just like Richard McCaslin.

He spent years warning of election fraud and shadowy hacking campaigns to disenfranchise patriots, and now he was claiming vindication. On Jan. 6, 2021, Jones would lead a column of pro-Trump protesters away from the White House Ellipse where the defeated president was speaking, towards the Capitol grounds.

“The Great Awakening will trigger the great rebellion, and the destruction of the New World Order,” Jones screamed from his bullhorn. Some of Jones’ followers smashed through the doors and windows shortly thereafter.

And it all started in Waco.

--

Justin Ling is a freelance investigative journalist and host of The Flamethrowers, a podcast all about how right-wing radio radicalized America.