With tensions between the United States and Russia at a level not seen since the Cold War, and likely not abating no matter the direction the war in Ukraine takes, our national security depends on the integrity of our intelligence community. The FBI and CIA must be able to securely plan covert operations, and to employ Russian double agents to carry them out.

In this context, just imagine an American FBI agent with top-secret clearance writing this letter to the Russian intelligence chief stationed in Washington:

“Soon I will send a box of documents. They are from certain of the most sensitive and highly compartmentalized projects of the U.S. Intelligence community. All are originals and aid to verifying their authenticity. Please recognize for our long-term interests that there are a limited number of persons with this array of clearances. As a collection they point to me I trust that an officer of your experience will handle them appropriately. I believe they are sufficient to justify a $100,000 payment to me.”

Sound farfetched? Not possible? Think again, because Robert Hanssen, an FBI agent assigned to counterintelligence and with top-secret clearances, began his nearly 20 years of spying for the Russians with a letter almost identical to this one. Hanssen, who started spying in the 1980s, is locked in federal custody and will remain so for the remainder of his life. But he was responsible for the betrayal of our double agents in Moscow, and leaked a steady pipeline of American intelligence to Russia for two decades. His legacy of treachery continues to reverberate today.

As the daughter of an FBI agent and a third-generation federal prosecutor, I grew up believing the men and women of the FBI were always the good guys, combatting crime and working hard toward the ultimate goal of keeping us all safe. My father was that kind of FBI agent, and so were the people I worked with. My father said Hanssen’s case was a devastating black mark against the Bureau.

While so many were working hard to keep Americans safe, Robert Hanssen was working just as hard to betray the agency he had sworn allegiance to and the people and country he had sworn to protect. His selling of national secrets to the Russians cost lives, including that of Dmitri Polyakov, one of our most effective Russian assets, and gutted operations critical to national security.

According to the Webster Commission report done after Hanssen’s arrest, Hanssen carried out of the FBI building a volume containing top-secret and special-access program information about “an extraordinarily important program for use in response to a nuclear attack.” The report puts a $10-billion value on the information he gave the Russians. In the process, he also besmirched the reputation of the FBI and branded it in ways that echo still: that it is an agency under siege, one unable to regulate itself from within, and one that is prone to infiltration. A 2003 report by the Justice Department’s Office of the Inspector General is harsh in its criticism: “[The FBI] suffered from a lack of cooperation with the CIA and from inattention on the part of senior management… The FBI failed to work cooperatively with the CIA to resolve the cause of these losses or to thoroughly investigate whether an FBI mole could be responsible for these setbacks.” In short, the FBI failed to police itself.

Hanssen is where he should be, in jail for the rest of his life, but still at large are questions about his motives, his psyche, and the damage he caused; whether the FBI has blinded itself to the lessons it should have learned; and whether we are any better protected today from a new Robert Hanssen than we were from the actual one who ripped the guts out of America’s secrets.

In writing my book, A Spy in Plain Sight, about Hanssen and the damage he caused to the FBI and to our country, I interviewed scores of past and present FBI and CIA agents, and I asked all of them the same question: “Can there be another Hanssen today?” The answer was a unanimous and emphatic “Yes!” This answer was often followed by an even more chilling qualifier: “And there probably already is.”

These agents know that the FBI and CIA have implemented more procedural safeguards because of Hanssen, including increased polygraphing of agents, and extensive financial disclosures by them. But fractured domestic politics and policies encourage present-day would-be spies. For example, when the majority of the Republican Party refuses to acknowledge the legitimacy of Biden’s presidency, or when seasoned senators and the minority leader of the House of Representatives continue to paint the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the United States Capitol as a tourist prank gone awry, the fabric of the nation is weakened.

These fissures quickly become wide cracks, not just on the American body politic, but in places like the FBI that are dedicated to defending the Constitution and on the front lines of upholding the rule of law. Such an onslaught has exponential ramifications, as it fundamentally undermines morale and functioning. It gives implicit license to those within such organizations who might have financial problems or are discontented with their career advancement or exist at the edge of a group culture—or are simply looking for a thrill to perk up their bureaucracy-bound lives—to give in to their own worst instincts, the dark angels of their psyche.

When that line gets crossed, you can institute all the polygraphs you want, run all the credit checks imaginable, but there’s always going to be one special agent with a high security clearance who slips through the net, scoops up a handful of vital secrets, and writes a letter to the Russians.

For a recent example of just how this line gets crossed, consider Jonathan and Diana Toebbe, the Maryland couple arrested last year for trying to sell some of America’s most closely guarded nuclear submarine secrets. Jonathan Toebbe, a nuclear propulsion expert who worked for the U.S. navy as a civilian, allegedly tried to sell nuclear propulsion secrets to an undercover FBI agent through a series of dead drops featuring memory cards hidden in peanut butter sandwiches, Band-Aid wrappers, and gum packages.

Toebbe allegedly sent a brown envelope to an unidentified foreign government in April 2020. Inside the envelope were sensitive U.S. Navy documents and instructions on how the country—believed by security experts to be a U.S. ally—should reply using an encrypted email service.

In Toebbe’s case, the foreign government turned over the contents of his envelope to the FBI, which began an undercover operation to catch him. But what if Toebbe had sent the envelope to the Russians? Would the Russians have turned over valuable intel to the FBI? I think not.

Of the 150 U.S. citizens convicted of or prosecuted for espionage between the start of World War II and shortly after Hanssen’s arrest, 42 percent of them were government employees. As Dave Szady, former assistant director of the FBI’s Counterintelligence Division, told me: “Is it going to happen again? Well, is the bank going to be robbed again? Is somebody going to be murdered again? How about corruption? You’d think politicians would learn that corruption isn’t a good idea, but do you think it will occur again? Of course it will. People commit crimes, and they’re not going to stop. And espionage is a crime.”

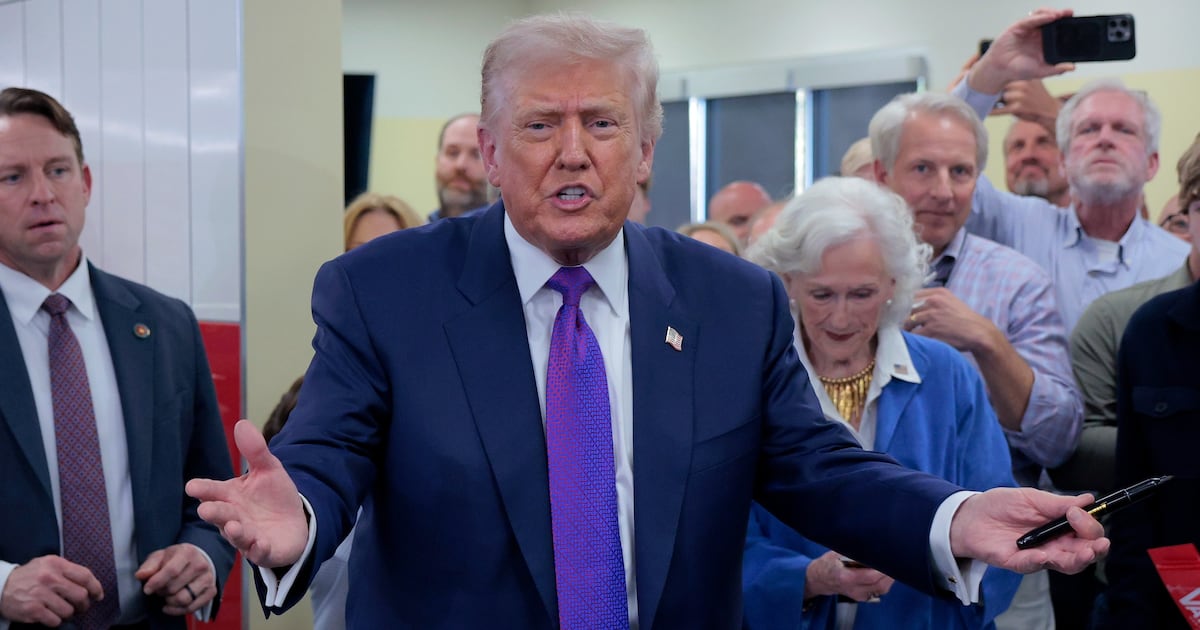

FBI agents arrest counterintelligence agent Robert Hanssen (C) near his home February 18, 2001 in Vienna, Virginia. According to the FBI, Hanssen had just placed a package of classified material in a park he had been using since 1985 to exchange documents with Russian spies. Hanssen is currently serving a prison sentence of life without parole.

GettyFBI Special Agent Jack Thompson, who was involved in the Hanssen mole hunt, said, “After 30 years in the FBI, 17 of those as the counterintelligence officer at the Department of Energy (DOE), I have no reason to believe that there isn’t a recruitment in place right now in the FBI, the CIA, and the DOE.”

And, if the FBI has a mole, how can it act effectively against another Hanssen or Toebbe? Even in a mature democracy, the rule of law can hang by a slim thread. An FBI that fails to police itself adequately or allows its mission to become subverted or its vast investigative powers to be abused could be the only difference between government of, by, and for the people and government by a tyrannous few.

Odds are, one special agent or officer may have already crossed that fateful line, and sold secrets to the Russians. And this time it’s not only U.S. assets and operations abroad that are endangered—it’s democracy itself.

The only way to strengthen institutions like the FBI and CIA is to restore integrity and confidence in the rule of law. To do that, we must stop politics from bleeding into intelligence agencies. Political fissures should always be secondary to the importance of the Constitution and democracy.

In analyzing Hanssen’s motive for spying, money is certainly a factor. But, according to his psychiatrist, Dr. David Charney, and his best friend Jack Hoschouer, Hanssen was also motivated by the glamour of being a James Bond-type character, by his constant need to be appreciated for his brilliant work, and by a warped sense that in turning over secrets to the Russians he would somehow make America stronger in the long run. These motivations are hardly unique to Robert Hanssen—they are universal in application.

A source I can identify only as one of the nation’s leading authorities on cutting-edge forensics—the kind of expert both Fortune 100 companies and government agencies rely on to avoid penetrations and find the culprits when they happen—told me, “Once you’ve been cleared and you’re inside the FBI or CIA or NSA, you’re trusted, so nobody’s watching you, and you can do anything you want. The kind of information that you have access to at that point would just blow anyone away. It’s better than make-believe.”

Real life, not make-believe, is warning us: We had better learn from past failings, like Hanssen, lest history repeats itself.