About once an hour—depending on your bladder, what you ate, how you feel, how your health is faring, and countless other indicators—you visit the toilet to pee or poop, or maybe both.

In most Western countries, the experience is pretty predictable: You sit on a white (mostly) porcelain bowl, do your business, then flush. You might not even think about it.

But if you do take a minute to think about it, you’re sitting on a wonder of engineering achievement, something that requires complex sanitation systems marrying bacteriology and urban planning, a technical powerhouse that miraculously disposes of urine and solid waste (and a whole lot else) with just the push of a lever.

For billions of people in the world, though, toilets are a luxury. Latrines or an outhouse—foul-smelling, outdoors, and festering with disease—are more common. For many, a hole in the ground has to suffice. Those have been the options for over a century, and not much has been done to figure out how to merge the hole in the ground with the toilet.

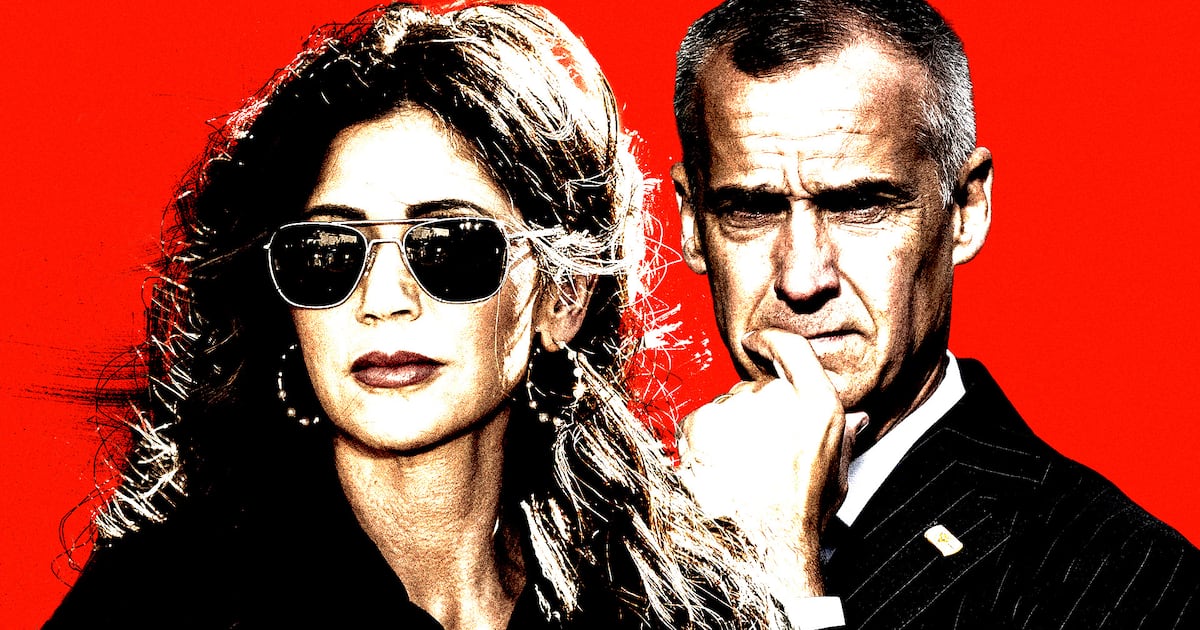

“It’s a hard problem, and I think that’s why it gets ignored,” Diana Yousef said.

She thinks she has a solution: the iThrone.

“What we’re using is a flushable pouch,” Yousef explained to The Daily Beast, while she was hopping from appointment to appointment in Boston one afternoon on a Lyft. “It’s a portable, evaporative, waterless toilet.”

The iThrone uses an innovative “self-flushing” technology by breaking the toilet down into two parts: a box-seat shell and a pouch with a polymer membrane that sits within a drum. The polymer membrane has twin powers: It’s able to evaporate the liquid contents of the pouch (our waste is about 95 percent water) while safely and odorlessly keeping the 5 percent of fecal matter contained.

That might seem futuristic, probably impossible: How do you pee and poop into a pouch that you can take anywhere that essentially sucks out the moisture of your waste without water?

Well, it helps that several years ago, Yousef served as a scientific adviser for a joint NASA and USAID initiative to figure out how to deal with water in climates that don’t necessarily support it.

Turns out, what makes sense for space also makes sense for the developing world. “Breathable materials can essentially evaporate water,” she explained. “We all learned in science class that evaporating water is a good way to purify it, you distill it. These breathable materials have the ability to allow you to evaporate water without having to pump in a lot of heat or energy.”

Yousef hit on the idea of taking this concept of breathable materials from space down to earth for families in need of a toilet, engineering one that would be portable, clean, and safe.

The technology is actually akin to the type of sweat-wicking sportswear you might be used to wearing at the gym, which keeps you dry while simultaneously letting evaporation suck up sweat and other moisture. Similarly, the iThrone's breathable technology means the inside of the pouch’s contents are sucked of moisture, and the outside of the pouch—the toilet bowl here—remains dry, which is important in hot, humid areas.

Yousef emphasized that breathability is crucial. That's because the installation of toilets in much of the developing world is difficult due to a lack of infrastructure and extreme climate. A toilet in the Western world is capable of being housed in a separate room within a residence because plumbing carries water away to an alternate location, where it’s usually cooler than the rest of the house.

Sweltering heat and lack of plumbing, however, make it not only smelly and potentially hazardous to maintain a bucket for waste in a house, for example, but making evaporation practically impossible. That can lead to waste sitting around; over time, that's a health hazard. The iThrone’s compartmentalizing of waste takes care of that issue.

It also could single-handedly reduce rape, assault, and sexual violence. After all, as Yousef points out, the fact that girls and women in developing countries often have to tread unsafe terrain to reach a latrine usually located in a dark, isolated place. It’s something she’s also thought about regarding refugee camps, where girls and women must use public restrooms that put their safety at risk.

“When girls and women have to use bathrooms at non-peak times, it’s an invitation to get assaulted and raped,” Yousef explained. That can also lead to a reverse health issue, of women not going to the restroom when they need to, which can lead to health hazards in and of itself, like bladder infections and urinary tract issues.

Yousef’s toilet, in a way, offers girls and women the freedom to go when they need to—something that hasn’t been afforded these women thus far.

Part of the reason why Yousef has thought so long and hard about toilets and water and sanitation is her upbringing. Her parents, immigrants from “water-starved” Egypt, inspired her to think about water. “It’s something that I’m appreciative of, that people have access to safe water and that it’s available to be reused and recycled and responsibility,” she said, recalling visiting her family in Egypt, who she described as middle-class, yet having to deal with the difficulty of finding and using a toilet that was both safe and clean.

And just in case safety and cleanliness aren’t enough, Yousef’s iThrone is environmentally friendly, to boot.

“It takes a pouch of membrane material to collect solid and liquid waste like your toilet bowl does, and the membrane sucks up the moisture portion …and renders it as pure, clean water vapor,” she explained, which helps reduce human contributions to methane in the atmosphere.

The five percent that doesn’t evaporate remains as “hygenically contained solid material” in the pouch—which can actually be processed by fecal sludge management services to collect whatever’s left over to make fertilizer or fuel. (Yes, your poop has value!) Best of all, it’s all safely contained within the pouch and dehydrated.

Indeed, Yousef’s invention hopes to inject one of the most vulnerable, perhaps embarrassing, and private of moments with a dose of dignity and technological prowess, one that has a multiplier effect across societies. “It has the ability to affect incomes, change livelihoods, help women, ease climate change,” she ticked off. “It can change everything.”

Yousef stresses you don’t have to have been to the reaches of the non-Western world to have dealt with toilets that make you feel uncomfortable. “Have you used a Port-o-Potty at an event? A toilet on a train or a bus?” she asked. “Then you already understand how horrible that [experience] can be.”

She and her team are now testing the iThrone prototypes. “We’re using it ourselves!” Yousef laughed. She said she’s aiming to have a model ready by 2019 that a family in a developing society could afford and easily install.