I am a writer. It seems unlikely yet inevitable that I should have become one. I didn’t go to college, have no degree, but I do have what they call, “a past.” I was named after my father, Willie, a con artist, card sharp, and sometimes garden-variety thief. For the first few years of my life, we lived under an assumed name. My father was wanted for grand larceny. I was three years old when they caught up with Willie. They shipped him off to a federal penitentiary.

My mother, Irene, had been a schoolteacher when she took up with him, but soon found herself resentful. Why should she be the only working stiff in the family? So, she quit teaching and took up drinking. When Willie was arrested, Irene stayed in bed for weeks, drunk or sleeping it off. Eventually she got up and went down to the welfare office.

I found out quick what they called welfare people: White trash.

Although Irene took Willie’s last name, my parents never married. At a slumber party I listened to the other little girls talk about their parents’ weddings, the white dresses, and churches. I found out that night what they called a kid like me: Bastard.

I learned how to lie.

I lied for Irene, but she was hard to contain. She did what she could to keep the wolf from the door. Sometimes the wolf got by her. There is only so much a kid can do. In and out of foster care, I left home at sixteen.

For the first half of my life, that world, those people were my secret. In my 20s, I wrote poetry and stories, much of it raw, ripped from my own headlines. I showed some to a boyfriend. “Jesus,” he said, incredulous. “You’re white trash.”

White trash. Again. It felt like a sucker punch. It felt true.

I left the boyfriend. But I couldn’t leave myself. So I took the trash with me.

My parents were at the heart of everything I wrote. They were what I’d come from. They’d made me, but did that make me them? Was I genetically doomed?

I started writing a novel and told my mother. She sputtered, flummoxed, “You think you’re just going to write a book and someone’s going to publish it?”

Aristocrats wrote novels. Bright lights. Not people like us.

I did it anyway. I didn’t want to be people like us.

When I got the offer from a publisher, my legs went soft. I was in a phone booth in Bodega, California calling home for messages. Receiver to my ear, I slumped against the glass of the booth and stared at the ocean. I hit replay as the tears streamed. I hit replay and replay and replay. This was it. No more dirty-faced welfare kid, no more trash. I was an author. I would be a bright light.

I wrote more books in the coming years. Woven through them was all I’d grown up with, the larceny and fury, the boldness and fear. But not one was published outside of Canada. I yearned for New York. If I could make it there, I could make it anywhere.

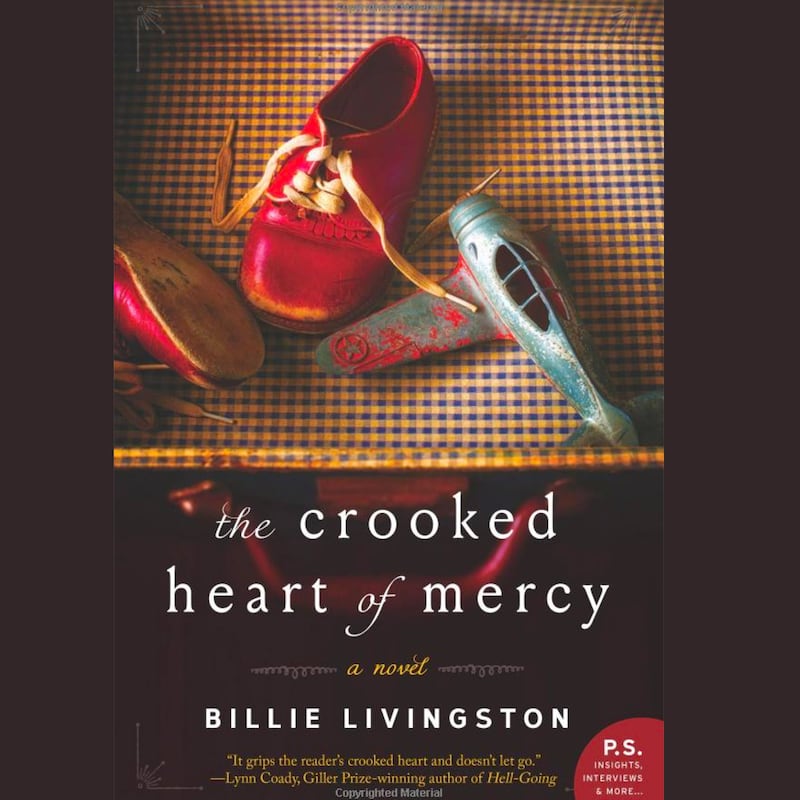

I recently wrote something different, far removed from my thinly veiled parents, a story about faith in the grip of crisis. As the book jacket says: This is the story of a man with a hole in his head, a woman with a hole in her heart and a priest with a hole in his vows.

I got a New York agent—a great one. And then it happened: We had an offer. It wasn’t a lot of money but it was solid and it was New York. My breakout book. The welfare kid in me sucked on those words like hard candy.

Author tours are rare these days, and with good reason. Scratch an author and you’ll find tales of woe, bookstore readings with an audience of one. But I was determined to get this right. To be bright. I wanted to meet readers and show the publisher how much it meant to me. I applied for a grant that would pay my way down the Pacific Coast. When the money came through—$1,500—plans were set in motion. Hope was officially launched.

On day one, I drove an hour to a bookstore in Bellingham, Washington, the first of a three-city tour. I was anxious. The book had already been out for two weeks, and unlike Canada, where my books are reviewed in all the major papers, it had been ominously silent in the U.S. Fear sometimes seems the ugly stepsister of Hope.

The event was scheduled for 7 pm. At 7:15 the room remained empty. Announcements echoed through the huge bookstore. People browsed but none came near. I stared at my feet. I wiped at my face as if it were dirty. I signed the store’s copies of my book and drove back home.

The next morning, I woke up hungover with embarrassment. Nobody had come. Not even the audience of one. And there were two more cities to go. I thought of the old chestnut, No matter where you go, there you are.

On Day 2, I arrived in Seattle. Pulling into the parking lot, I noticed a couple of people dashing toward the bookstore and felt a glimmer of promise. I walked in just as an announcement for the evening’s event came over the PA. Staff escorted me to the reading area.

Bellingham all over again: Nothing but empty chairs. No book reviews. No audience. I sat down and closed my eyes for a moment. When I opened them, someone had joined me. Three seats over was a young brown girl with wide eyes with a mouthful of braces. The event coordinator glanced from me to her. “Well? What do you want to do?”

The girl blinked at me, her face expectant. She couldn’t have been more than seventeen. I took a breath and walked up to the podium. I told her about the novel. She smoothed her skirt and nodded. I read two chapters.

At the end, the girl stood up. She flashed her braces. “Thank you,” she said. “It was only me here and you still gave the talk.”

I asked her name. “Faith,” she said.

It was only Faith, but faith was what I needed. She extended her hand. I took it and held on a little too long.

The next day I got on a plane to San Francisco. I rented a car and drove downtown early. The bookstore was in the Ferry Building Marketplace. Just outside the door a display poster barked the book’s title, The Crooked Heart of Mercy. I glanced at the store’s event calendar and thought of Faith as I read all those famous names on the schedule. I wished I could have packed her along.

At 7 p.m., I stood at one last podium. This time, I had an audience of four. As I started to read, a straggler ambled into the store and made his way to a seat in the front row.

I glanced at his long grey hair, his beard wild and white against weathered skin. He clutched a neatly folded foil thermal blanket to his chest. An old woman sat in the third row, leaning on her cane, impervious as she stared out the window. I took a drink of water and tried to find my place again.

When I finished, a woman at the back shouted, “What happens next?” These two characters end up at a spiritualist church, I told her, where people talk to the dead.

“I’ve experienced that.” The man with the blanket. He apologized for interrupting. He told us about a time many years ago when he walked down the coast for 36 hours straight. He believed he’d seen the dead that night. “You know when you put a sheet in front of a light and people cross in front of that light and what you see are shadows? That’s what I saw. I’m open to the idea of spirit.”

The woman with the cane turned from the window, her expression caught between pain and anger. “This vision you had, you said you’re open to it. I haven’t experienced anything like this and I’m not open to it. I’m not. Why are you? How does it happen?”

The six of us exchanged thoughts about mystical encounters, about faith and spirit. The man spoke of when his mother was dying, how he’d read The Tibetan Book of Dying. She was his best friend. He read it all to her and she loved it. He told us about being a 67-year-old gay man and growing up Presbyterian in Kentucky. He’d been living on the streets for many years now.

His eyes drifted to the book display. “That’s you, Billie Livingston? Where does Billie come from?”

That stopped me. “My father was William and I’m Willa.”

“Your name is Willa? I can’t believe it. I’m right in the middle of one of my favorite books in the world, One of Ours, by Willa Cather. And you are Willa!”

I looked at him, wondering, Where did you come from?

Eventually, our evening came to a close. As people gathered their things, the man with the blanket said, “This was such a wonderful time! I’m sorry that I came in late. I would dearly love to buy a book but I don’t have any money.”

Before I could respond, the woman from the back row now shouted from the cash register. “Hang on. I’ve got a book for you.”

“Me?” he said, incredulous. “You are giving that to me?”

Soon he set the book down for me to sign. I asked his name. “I’ll give you the name that the Buddhist monks gave me,” he said. I carefully wrote as he spelled. I looked up into his eyes, searching for words. “In the story,” I said, “there’s an alcoholic priest. And he is a gay man. He’s often lost and in a state of chaos and yet he is the character who has true grace, the one who touches people and brings them together.”

“He is?” the man said. “That’s wonderful. I can’t believe this night is happening. I feel like I’m going to cry.”

Before he left, he knelt beside my chair and suggested that I read a book called, Mother of Sorrows by Richard McCann. “I think you’ll like it very much,” he said. “If you can find it, it seems like a book for you.”

When he left the store I thanked the woman who’d bought him my novel. “It was easy,” she said. “I always do the easy thing.” It wasn’t, I said. It really was a gift. “Funny,” she added, “I was just killing a few hours before I had to travel when I saw the sign that said you were a Canadian author and I thought: Canadian? I’m from Ottawa.”

As I walk to my car in the early evening light, the streetlights are coming on around me—the colors, the traffic—it’s all oddly disorienting.

Driving over the Bay Bridge, I look out at the city lights glinting on the water and there’s an electric kind of giddiness in my gut. I fumble with the radio, and then switch it off. I’d rather it be quiet. Better to hear the light of those strangers: Faith with her braces, the woman from Ottawa, that homeless Kentucky man. Their glow has nothing to do with reviews and numbers. Or foster homes and white trash. Their bright light is the spark that connects far-flung strangers. Those strangers are me. They are us—all of us: living lights, love glinting, razing the darkness with hope.

Billie Livingston is the award-winning author of The Crooked Heart of Mercy and three other novels, a collection of short stories, and a poetry collection. Her novel One Good Hustle, a Globe and Mail Best Book selection, was nominated for the Giller Prize and for the Canadian Library Association’s Young Adult Book Award. She lives in Vancouver, British Columbia.