At the 1992 Academy Awards, Disney’s Beauty and the Beast claimed the trophy for Best Original Song, surprising no one. Three out of the category’s five nominees that year were Broadway-inspired ballads and showstoppers (“Belle,” “Beauty and the Beast,” “Be Our Guest”) from the animated fairy tale, with music composed by Alan Menken and lyrics by Howard Ashman.

Liza Minnelli, the award’s co-presenter, wore a red ribbon pinned to her breast as she congratulated Menken, who took to the stage alone. Little loops of red adorned many stars that night, silent reminders of the AIDS epidemic decimating the gay community. Menken wore one as he thanked Angela Lansbury, Celine Dion, and a handful more on Ashman’s behalf. On him, it bore extra weight: Complications from the disease had killed Ashman, his songwriting partner and friend, eight months before the film’s release.

It was then that Bill Lauch, Ashman’s surviving partner, appeared at Menken’s side and calmly said aloud what the ribbons could not: “This is the first Academy Award given to someone we’ve lost to AIDS.” He and Ashman, the prolific and brilliant lyricist behind The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, Beauty and the Beast, and Little Shop of Horrors, had shared a home and a life together, he explained. And Ashman had been lucky: He had lived his final months in an atmosphere of love and support, “something everyone facing AIDS not only needs, but deserves.”

Lauch’s speech is still remembered as a landmark moment for LGBT visibility, at a time when stigma and confusion around the disease—which had killed 200,000 people at that point—coincided with an unprecedented spike in hate crimes targeting the gay community. Lauch had been nervous as he approached the stage, concerned he might forget the words. Still, delivering the speech had been his idea, so he pushed on.

AIDS, he remembers now, had often been cast “as something that we don’t have to reckon with, that these are people who may deserve the disease—it’s you know, drug addicts and homosexuals, and the people on the outside of society,” he says in a phone conversation. “I thought, this is an opportunity to show people that this virus is affecting things that they care about, that matter, that create and contribute to our society and our culture. And I don’t want it to be wasted.”

Ashman’s posthumous Oscar win for Beauty and the Beast is one of several bittersweet moments at the end of Howard, a touching documentary about the late lyricist directed by Bill Hahn, which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival.

The film is riddled with gems from the production of now-iconic films—footage of Ashman coaching Belle voice actor Paige O’Hara through her first big number, for instance, or of Angela Lansbury weighing in on the preferred milk, sugar, and tea bag placement for her character, Mrs. Potts—and insight into the life and legacy of a man whose lyrics everyone knows, yet whose premature death fewer are familiar with.

That’s strange, in a way, considering how omnipresent Ashman’s work remains 27 years after his death. Colleagues remember him as a kind but unstoppable force, known for having clear, specific visions of songs and stories that shaped the final product as much as any of his film’s directors. His work on Beauty and the Beast, The Little Mermaid, and Aladdin became so indelible that Disney is trotting them all out again, this time in “live-action” remakes.

Ashman did not intend for his work to be read personally or politically. Even the pitchfork-wielding villagers of Beauty and the Beast’s “The Mob Song,” his surviving partner, sister, and colleagues mostly agree in the film, do not boil down simply to a “metaphor for AIDS,” as last year’s Beauty and the Beast reboot director Bill Condon has asserted.

Still, the songs cannot be divorced from their context. With this documentary Hahn, who worked as a producer on The Little Mermaid, has ensured that even as Ashman’s celebrated songs fall under the spotlight again—especially as the LGBT community finds itself in a renewed struggle for equality—the story of the man who wrote such clever lines isn’t forgotten either.

Howard begins by highlighting early work from Ashman, stretching back to his childhood, that testifies to his preternatural capacity as a writer and storyteller.

His knack for crafting whip-smart lyrics that could drive a story’s plot forward in astonishing time (think Ursula’s signature sass in “Poor Unfortunate Souls,” in which the villain meets Ariel, lays out her motives, fulfills the girl’s dream of being human, and kicks off the film’s second act in just four minutes) quickly propelled him to New York, where he met Menken while directing and writing lyrics for an adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater.

Critics thrashed Mr. Rosewater. (Vonnegut loved it.) But the sting of its reception drove Ashman to get weirder and wilder with his next project: a musical adaptation of the 1960 no-budget horror movie sendup Little Shop of Horrors. With lyrics and a book by Ashman and ’60s rock, doo-wop and Motown-inspired music by Menken, Little Shop found near-instant success off-Broadway. Four years later in 1986, the Muppets’ and Star Wars’ Frank Oz adapted it into film of its own.

Ashman cuts a dashing figure in photographs from the time. Menken remembers him chain-smoking in torn jeans and a leather bomber jacket at their first-ever meeting, in a tone resembling a little brother’s admiration. (“He had a lovely singing voice,” he adds.) In interview footage, Ashman is soft-spoken and sincere, yet exacting, and a veritable library of musical-theater history. By the time Mr. Rosewater debuted, he was 29 and had founded his own theater company and written and staged three plays. By the time Little Shop made him a theater-world star, he was 32.

It was around then that Ashman met Lauch, the love of his life with whom he first locked eyes at a bar in the Village. A few days later, he called to ask him out. Lauch remembers his proposal: “Have you ever been to the Grammys? My cast album is nominated, if you’d like to go with me,” he says, laughing. Within months, the pair was living together. Lauch, an architect, began work designing a home for the two of them in upstate New York with the “little flush of cash” that had come in from Little Shop.

Little Shop’s success, however, gave way to a particularly devastating failure for Ashman: his critically panned musical adaptation of the beauty pageant comedy Smile! Disillusioned with New York’s theater community, he turned to Disney motion picture studio chief Jeffrey Katzenberg, who for months had tried coaxing Ashman out to Los Angeles. This time, Ashman agreed, eager to help revive the studio’s declining animation division. “The last great place to do Broadway musicals is in animation,” he later declared in a crew meeting. “It’s a whole other world.”

Assigned to work with directors Ron Clements and John Musker on The Little Mermaid, Ashman hired Menken as composer. Together they brought a Broadway sensibility to the proceedings. In archival footage, Ashman is seen lecturing crew on how to tell stories through song. A protagonist’s “want” song, he maintains, is indispensable: songs like “When You Wish Upon a Star,” which launch entire musicals with a character’s dream.

When Katzenberg suggested they cut “Part of Your World” then (sung by Jodi Benson, who had co-starred in Smile!), fearing kids might lose interest, Ashman didn’t mince words: “Over my dead body,” Katzenberg recalls hearing from him. “I’ll strangle you.”

As Ashman began engineering Disney animation’s second golden age, his body began to deteriorate.

On an afternoon when he’d been scheduled to speak at a 92Y conference in New York, he learned he had HIV. Audio of the interview, which Ashman insisted on going through with, lands heavily. He demurs when asked about future plans for his career, sounding distracted.

He concealed his diagnosis from Disney for a year and a half. “It was the 1980s, Disney is the biggest producer of family entertainment in the world, and here is a gay man writing songs and producing songs for kids. It wasn’t assumed that everyone would be OK with that,” Lauch remembers now. “He was afraid. We were both afraid.”

Ashman’s awareness of his sickness appeared to fuel a certain impatience. In the film, Menken recalls an ill-fated Walkman Pro whose microphone stopped working: “He smashed it against the wall.” There were hurt feelings afterward. “Is it me?” Menken remembers thinking. “Am I just that inept as a composer that he’s that frustrated?” He says he excused himself, left the room, and cried. “It was just so hard.”

Howard - Be Our Guest from Don Hahn on Vimeo.

Press obligations for The Little Mermaid became Herculean tasks. Ashman was faced with a two-day junket at Disney World, for which he was expected to ride rides and complete interviews, all while queasy from daily IV treatments. No one with him apart from Lauch knew about his diagnosis. Prior to the trip, Katzenberg had screened and hated “every minute” of the movie, sending Ashman back in for rewrites.

For a moment at the park, though, it felt worth it. Lauch recalls tears on Ashman’s face at the sight of a then brand-new Little Mermaid parade, as characters performed songs he’d written. “I think it dawned on him that the work he’d been doing there was going to live on,” Lauch says. “It was going to become part of this canon of pieces that Walt Disney has in their collection. And it would reach many people.”

It wasn’t until he and Menken won their first Oscar together for “Under the Sea” that Ashman decided to break the news. (Menken says he spiraled at the prospect of a “serious talk”: “Does he not want to work with me anymore?” he wondered anxiously. He is now working with younger songwriters including Lin-Manuel Miranda and La La Land’s Justin Paul and Benj Pasek on Little Mermaid and Aladdin live-action adaptations, respectively.)

Ashman’s colleagues were devastated. But Disney readily facilitated travel so that Menken, animators, and their storyboards could fly to Ashman in New York, where they began work on Beauty and the Beast. By then, Ashman had also begun writing demo songs for another idea he’d brought to the studio: a musical called Aladdin. “They recognized that Howard was an asset,” Lauch says. “Sometimes doing the right thing is also the good thing for business. In this case it was.”

Ashman had begun feeling weaker, however, and could only clock in a few studio hours a day. (The Beauty and the Beast soundtrack was recorded like a Broadway cast album, with a song’s actors all in one place performing together with an orchestra.) Neuropathies, breakdowns of nerve endings, soon began taking his senses away from him.

And still, he kept working.

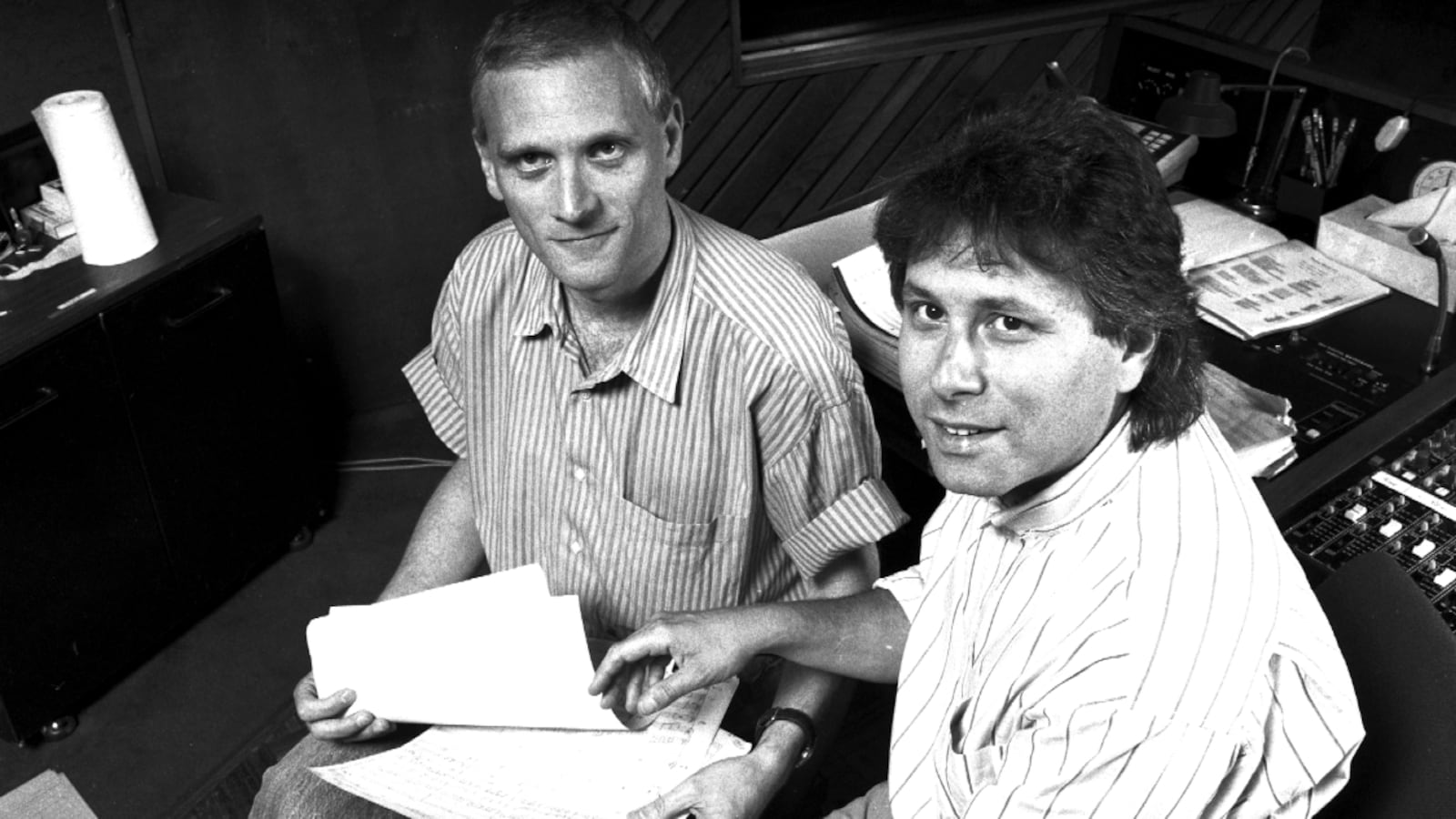

Alan Menken, Howard Ashman and others during the recording of 'The Little Mermaid.'

Tribeca Film FestivalLauch remembers the last few months of Ashman’s life as a blur of hospital visits and work obligations, and little time to spend together just as partners. He regrets the decision to build the house. “I had designed this house for our future, but now we had no future,” he says in the film. “I think we had said our goodbye long before he was actually gone.”

Chris Montan, now an executive music producer at Disney with credits on Frozen and Big Hero 6, recalls holding a phone up to Ashman in a hospital bed during their last sessions on Beauty and the Beast. Menken recalls writing the Aladdin showstopper “Prince Ali”—a fast-paced song that rhymes “calm” with “Sunday salaam” and “Ali” with “coterie”—on Ashman’s bed at St. Vincent’s Hospital on a portable keyboard.

The lyrics Ashman wrote for “The Mob Song” resonate darkly in this context, especially played over footage of real-life crowds bearing signs condemning AIDS victims as subjects of God’s punishment: “We don’t like what we don’t / Understand and in fact it scares us / And this monster is mysterious at least,” villagers sing as they march toward Beast’s castle.

Lauch calls the song a “perfect manifestation of people seeking a scapegoat for their troubles and identifying a villain and wanting to exterminate it.” Others, including Disney Theatrical Group’s Thomas Schumacher, go so far as to call it “an AIDS metaphor, done in a time when I don’t even know if the creators were aware that they were creating it.” Ashman’s sister Sarah Gillespie, for her part, calls that theory a “bunch of hooey.”

Today Lauch maintains he sees no direct intent in the song, and “didn’t feel it at the time either. But I think all works of art are created in the realm of the experiences of the people who create them and the times that they’re created in. So clearly Howard was drawing on a sense of inciting to violence and this mob mentality that had gone on for several years in the country regarding the AIDS crisis.” The tone felt appropriate to the piece, he says. “But believe me, it was not intended to highlight his own personal plight in that regard.”

The final minutes of the film feature goodbyes from Ashman’s colleagues. Benson remembers visiting an emaciated Ashman, kissing his cheek, telling him he was loved, and breaking down when she left the room. Katzenberg remembers Ashman’s “barely whisper of a voice,” transformed from the one he’d often heard in the studio. And Menken remembers an uncanny dream.

It happened the morning of March 14, 1991, with Beauty and the Beast still months from finished. He dreamt he was visiting Ashman in the hospital when his friend asked for help getting up. “So I put my arm behind his back and just gently lift his body up but it has no weight,” he says, “and I look and see he’s wearing a black robe and I put him on the bed.” Menken claims he awoke from the dream around 6 a.m. “That was when Howard passed away.”

Lauch spends most of his working time these days helping to manage Ashman’s estate. He says he understands why only few of the legions of Disney fans who know Ashman’s every lyric know what happened to him. “Howard was definitely not that person,” he says. “He didn’t seek the spotlight unless he was talking about his work or some other work that he was interested in.”

Still, a dedication at the end of Beauty and the Beast is addressed to Ashman, the man who reinvigorated Disney’s animation studios and inspired a new era of musicals—one now coming full circle back to the stories he and Menken told through song: “To our friend, Howard, who gave a mermaid her voice and a beast his soul, we will be forever grateful.”