Born in New York City to Chinese parents, “creativity was never brought up in my childhood,” photographer Baldwin Lee recalled in the introduction to his new monograph, the eponymous Baldwin Lee. “Redemption occurred by surprise in my sophomore year when I enrolled in a photography class.” He had two formative, formidable influences—Minor White while an undergrad at MIT, Walker Evans while doing a master’s at Yale—who “were the equivalent of having studied with Matisse and Cézanne.” Lee was briefly Evans’ personal printer, handling negatives from Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

Lee—who established the photography program at the University of Tennessee in 1982 and taught there for over three decades—found his own photographic subject while traveling through the American South. During every break from teaching between 1983-89, he went on the road. He gravitated toward Black neighborhoods, “where indicators of success were replaced with the stigma of neglect,” Lee wrote. “If I had trouble finding these places, I would visit the town police station telling them that I was a photographer with expensive cameras and handed over a highlighter marker, asking them to circle areas I should avoid. Of course, I did the opposite.”

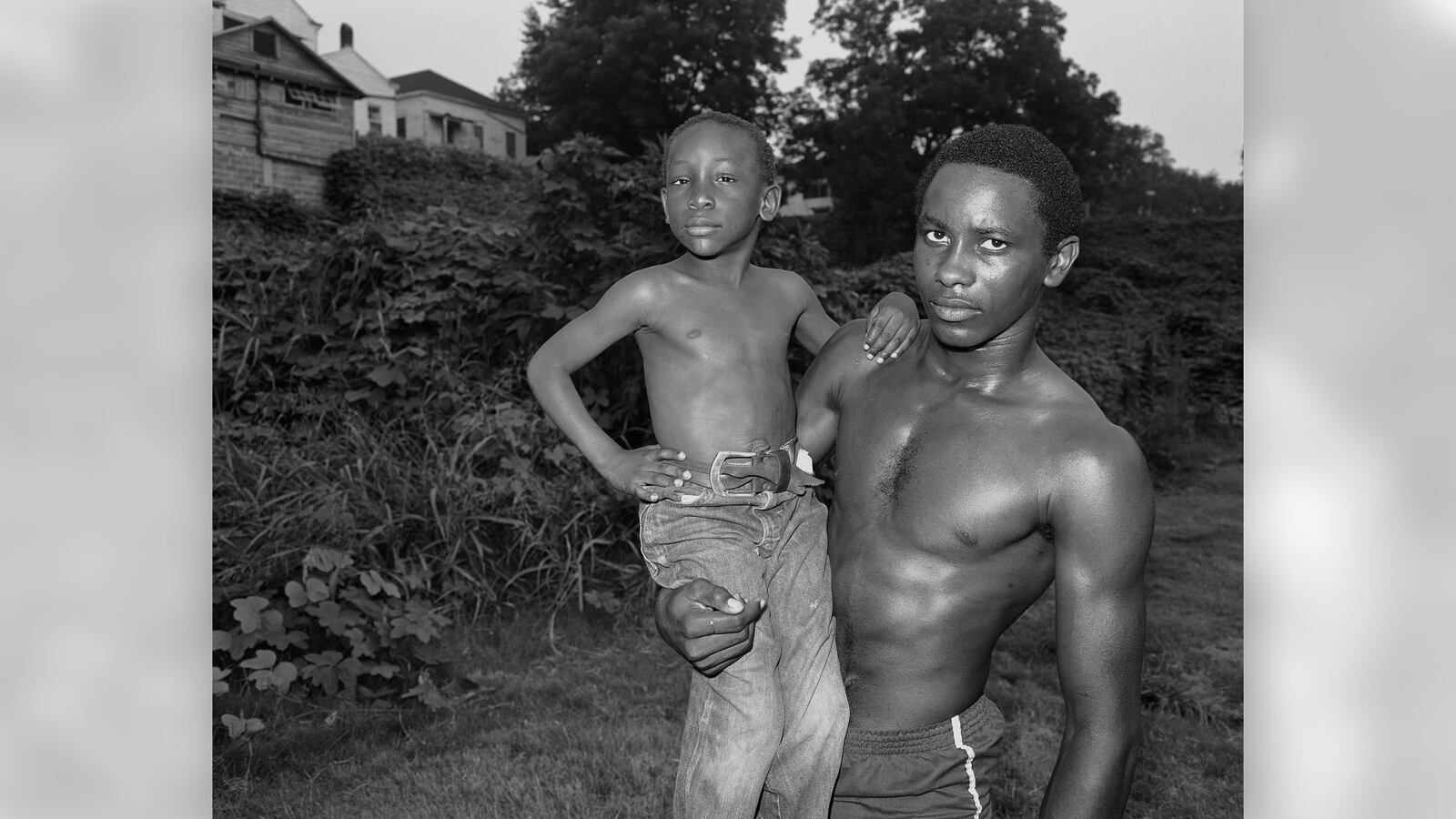

He worked with a cumbersome, indiscreet tripod-mounted 4×5 view camera, which required long exposure times but yielded stunning results aesthetically. Most interactions with locals occurred in front yards and on porches. He would explain his approach, then give his subjects specific directives—but always allowed for the serendipitous: “There is a beauty in this process that exploits the unintended.”

As a member of a minority himself, Lee understands the feeling of being overlooked and underestimated. He recalled that “when we first moved to Tennessee, my wife—she’s Irish Catholic from Boston—and I opened up a bank account. We sit down and the woman opening the account is talking only to her. At some point, when we had to sign, she asked, Does he have a social security number? At which point my wife said, Why don't you ask him?”

In addition to the striking monograph, filled with dignified portraits that outshine the subjects’ grim circumstances, an exhibition of Lee’s work is on view in New York at Howard Greenberg (September 22-November 12), with another show planned for next year at David Hill in London. Lee talked to The Daily Beast about racism across eras, the exuberance of Black hair, and quitting while you’re ahead.

Let’s discuss your editing process, because the book begins by stating there are 88 plates from a selection of… ten thousand! How did you land on the edit for this book?

The publisher at Hunter Points Press, Barney Kulok, approached me four years ago. I sent him a folder of 20 pictures I wanted to have in, and then he picked the rest, so I've just been a passenger watching it unfold.

What state was your archive in?

Panic sets in on April 14, the day before taxes, because I am, like, just totally hopelessly unorganized, and have no interest in doing that stuff. When Barney asked how many images I had, I had no idea. I proceeded to engage in a forensic-slash-archeological dig: It took me maybe three weeks to just get everything together in one space. I don't have any inventory; I counted them out for an approximate guess. I made this gizmo—a hinge on top of a light table—and I put my iPhone in it, and it took me another couple of weeks to send 10,000 plus pictures. Even though I have a degree from MIT, I know nothing at all about technology—the school should take my diploma.

From the trips through the South I made over a six-seven year period, I'd come back with a stack of exposed film and would develop it all. From memory, I had certain images I had hopes for, and I would print those. The rest never saw the light of day for, like, three decades. I've never seen 98 percent of my work.

Did you have any framework in mind, at the time, while taking these pictures—like an exhibition or a book? Or was it just about discovering your own photographic eye?

In graduate school—this is in 1973 at Yale—our program had four students a year. When we met for the first time, one of the guys, from Sacramento, said, Baldwin, I hear you're from New York. He goes, Can you draw me a map of Soho? Before the first day of class, he already had his career planned: He would go to the right openings, parties, the list of people he needed. I mean, that's fine. But I was totally professionally unambitious. I had a teaching job, and I would find out what the schools needed to keep me on staff and promote me and get tenure. And I would do just that. I did the minimal amount of stuff. I just have no interest whatsoever in self-promotion.

There's something very impressive about operating without a strategy. Especially because strategy can warp what you do. It’s rare to be interested in something without a “purpose” for it—to just purely follow your interest.

Yeah, it's like fly fishermen go out not because they want to have something mounted on the wall; they just love the act of wading out into the water and standing there. It’s just a totally personal thing.

At a dinner party a while ago, I told a painter I’ve known a long time about how I've been resurrected from the dead—somebody moved a stone away, and I crawled out and saw the light. She was congratulating me, at which point I said: Why didn't this happen when I was making these pictures? I could have been monetized, I could have been somebody, I could have been a contender! But she echoed what you said: that it's much better for it to happen at this point, in the late innings of my life. I was freed from having to think about “what the gallery wants next.” It was not in the equation. I would not have worked well with that pressure. I was able to pursue what I wanted to pursue on my own terms.

In the essay by writer Casey Gerald, he frames your work as resonating with “this moment of political turmoil, racial reckonings,” as well as this “Black cultural renaissance.” Although these images are more than three decades old, they have this incredible synchronicity with the present moment: connecting to something that is ongoing, and that's extremely current. Do you have a fresh gaze on the work today?

When I started photographing, Ronald Reagan was president. When people in the art world started to take notice, it was Donald Trump, and then there was George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. The people who are looking at my work now are not seeing it independently of the [present] political climate—they see it as an opportunity to contribute to the ongoing conversation about ethnicity in the history of this country.

Back then, these were almost immediately relegated to the specific time and place where they were made, and therefore categorized as a “niche” kind of thing. People would point to, Oh, look at those clothes, or Look at that car. But if I'm photographing a family on a porch and they have an old console, the picture would be the same if there was a flat-panel Sony there. My interest wasn't in the context of what surrounded them, but always what I saw in somebody. It doesn't look dated because it's not about the time.

When I was still teaching, I began taking English literature and writing classes. In learning about writers, the word “interiority” is often used, and that was exactly what I wanted to do in my photographs. I wanted to—through the mask of reality—reveal this interiority, just like in fiction. What you're ultimately talking about is a very essential, basic thing at the heart of who each of us is. That's why I think my pictures escape being assigned to a period.

That's an apt parallel! Were there other creative influences—things outside of photography—that informed your work?

Creativity… I don't like to go there. I'd rather talk about curiosity and perception.

OK—go on.

I've always had the ability to be within a moment and also outside of the moment simultaneously. I remember going to arthouse theaters in Manhattan—Bertolucci’s movies, or whatever—and being a terrible member of the audience because everybody would be totally focused on the screen. But I would always, like, see the exit signs. I’d always see the heads in front of me. Back in the day, when you could smoke, I loved to see the smoke in the projector. I don't think I was missing anything in the movie, but I always saw it in a context.

Being from and studying in the Northeast, what drew you to the South originally?

It was very practical and mundane. After I got my grad degree at Yale—that was in 1975—they hired me on to teach and I taught for four years there. And then I took another job up in Boston at Mass Art. And then I got this phone call from a department head in Tennessee, and he said he just met [photographer] Tod Papageorge, who’d recommended me to him. So he said, Would you be interested in applying for a job? It was in February; it was totally miserable in New York and Boston. You know, the snow is white for like 15 minutes, and then it begins to look like the color of what painters clean their brushes in.

That sludge color.

Yeah, just the worst color. Like the color of the sky in New Jersey over the turnpike. There's no name for that color.

But it's very precise—I know exactly what you mean.

Yes—that color. And I got to Tennessee and it was charming. I got off the plane and then the department head picked me up in his new white Mercedes and drove me to his home in this beautiful Southern neighborhood, and he and his wife gave me martinis.

As a non-studio photographer, I wanted to find out what was around there to photograph. I went on a random ten-day trip, I drove 2,000 miles, took a whole bunch of pictures of everything: landscapes, architecture, pictures of people—old, young, well-to-do, not well-to-do, everybody—but while I was taking the pictures, I was most interested in photographing Black Americans. So that started it, and then 10,000 pictures later, I quit.

I was kind of stunned about that. In the book interview with Jessica Bell Brown, you list several reasons for why you quit photography—but given the “antenna” that you just described earlier… Those reflexes are the way you look at the world. I hoped for a better understanding of why it felt right to quit.

You know, one of the reasons was, I was just emotionally and psychologically exhausted. It was draining to have to immerse myself in the lives of a lot of people who were relegated to live just absolutely horrible lives, and then come back to this middle-class one. I had become a father and I would look at babies being brought up, I would feel guilty about the contrast. People can understand that as a reason.

But there was another reason too: it was that I knew I had done my best work. I absolutely knew it. And from my little bit of knowledge of the history of art, with some notable exceptions, most creative people do their best work in five to seven years. Unless you're Picasso, you're unable to sustain it for decades. And if you were able to sustain it for decades, there'd be so much work that it'd no longer be good. It can't be good unless it's rare.

For me, the project of the South happened at the perfect time in my life and career. I was prepared. I didn't have to ramp up, I just hit the ground running.

With Walker Evans, I was his darkroom assistant for a year. I printed for him in the last year of his life. John Szarkowski made the observation that almost everything that we know about Evans and his work was done in an 18-month period. He lived 40 years after he did his best work. He was a very sad, lonely, and bitter man. He tried for 40 years to take other pictures, but you could have taken every picture he had ever made since 1936 and thrown them all in the trash. You have to be realistic. What is so hard about that? Being young and dumb and fearless is great. I can't do what I used to do.

There's one more aspect about it—I talked about this in the book interview. I think that when an artist persists on working past their period of having done their best work, they're engaging in two forms of fraud. One, they're lying to themselves. And worse than that, they are dishonoring and disrespecting their media. They should know enough about what made their medium great and not want to just throw crap on top of it. They should know: You just need to cut it out. The medium was good to you—be grateful and move on to something else. Don't just keep doing it because you don't know what else to do, or because you're going to get accolades, or because you're going to make money on it. Stop that! Give me a break. They're making fraudulent work knowing full well that it's a lie.

I guess people cling to: Well, who knows what could happen. But you're right that people can often identify their limits, yet continue working in spite of them. It takes a certain level of realness and courage to say, Now I have to pivot.

Let me just put it this way: I'm not gonna pay $5,000 for a ticket to see Bruce Springsteen. I like “Born to Run.” It's great. But if the guy is unable to fit into those jeans, I have no interest.

Fair enough! So, with the attention that you'll get from the book, if someone asked you to consider a new project, you absolutely wouldn't?

Oh, yeah. Totally. That would be shut down.

One photo of yours that I really loved—and which stands out from the overall solemn tone of the images—features this woman surrounded by wigs displayed on her car. It’s very playful and joyous. Could you talk a little bit more about the circumstances of that photo? I thought it was an interesting exception.

The place of Black hair in cultural history—it’s a thing. One of the reasons why I took that picture was that the woman obviously liked to spend time in front of the mirror: Every day was Sunday, you know. She was selling wigs, and she wanted people to feel good about how they’d look, and her wigs would help them do that. She was like a service provider, you know?

When I was photographing, I would have all these heavy socio-economic, political thoughts, the enslaved history, the plantation—you can't help but think about all this stuff. But then, you know, in my ambition to be a good photographer, you can't just hit that one note.

Before I came to the South, when I was up in Boston, I was deathly shy. Can you believe it? I did take pictures of people, but surreptitiously. But I wanted to use my tripod-mounted view camera. The first issue isn't photographic—the first issue is walking up to somebody and asking for permission. And so I spent a couple of years making terrible, terrible pictures, forcing myself to walk up to people. I worked really hard and had no reward. I just kept doing it until I got to the point where I was fearless. I could walk up to anybody, I could knock on doors. By the time I got to Tennessee, I felt that I had access to anything I wanted. And people like me: I'm not threatening, I'm five feet seven and a half and I don't weigh anything. So if I asked 20 people, 19 would say yes.

That’s an amazing stat.

Yeah, I should run for office.

You absolutely should.

If I didn't do photography, I would have been a televangelist. Step aside, Jim Bakker. Step aside, Joel Osteen. I'll show you how to do this. I know they have the megachurches, but are there internet ministries? I could just change the background. And not wear pants, like Jeffrey Toobin.

Students loved me in class, because I start to talk about something photographic, but then I get off topic… Thank God I wasn't teaching surgery. I would have killed thousands of people. But, you know, the world is not gonna be any worse with another bad picture.