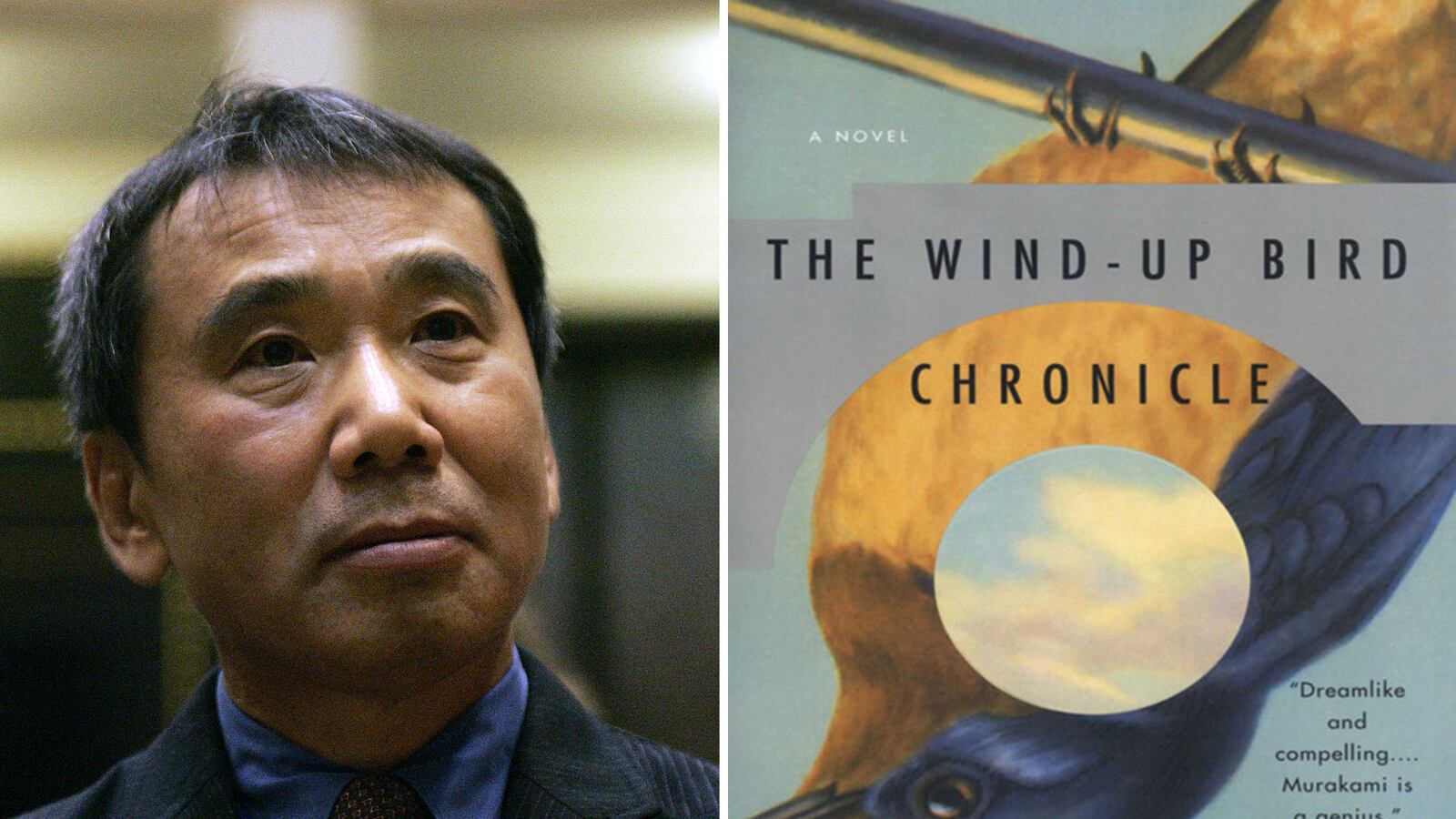

In a scene in Haruki Murakami’s novel, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, a man descends into a dry well to do some thinking. He has a lot on his mind. His cat has disappeared. So has his wife. To make matters worse, a malevolent teenage girl has pulled up the rope ladder he used to get down the well, stranding him there in the dark. The man tells the girl, who is listening from ground level, about how he and his wife had tried to start a new life together and reinvent themselves, “like building a new house on an empty lot.” The girl tells him that’s impossible. “You might think you made a new world or a new self, but your old self is always gonna be there, just below the surface, and if something happens, it’ll stick its head out and say ‘Hi.’”

As readers of Murakami know, his books are filled with stuff like this. For novelist Jonathan Franzen, it’s moments like these that gave him an emotional response. “My experience at mid-life is that I have this busy modern life,” Franzen said. “And only at night, and when reading certain books, do I fall down into a tunnel that takes me back to a more enchanted place.” The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle is one of those books for him. “While you’re reading it, everything in the world feels different,” he said. “And that for me is the mark of a great novel … I think it’s one of the great novels that’s appeared anywhere in the world in the last 30 to 40 years.”

In Japan, the release of Murakami’s new novel, Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, has been met with a kind of mania. It became the fastest-selling book ever on Amazon Japan. It will hit American shores next year, and Philip Gabriel, who has translated several of Murakami’s works, confirmed to me that he will be translating the new novel; he’ll be the sole translator and won’t be splitting the duties with Jay Rubin, as another report has suggested. In the U.S., there are close to half a million copies in print of Murakami's most recent novel to be translated into English, 1Q84, according to the publisher.

But popularity aside, Murakami hasn’t been universally praised. The New York Times has been particularly mixed about his books and was soundly critical of Murakami’s magnum opus, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. “In trying to depict a fragmented, chaotic, and ultimately unknowable world, Murakami has written a fragmentary and chaotic book,” critic Michiko Kakutani wrote in 1997. More recently, the Times’ other critic, Janet Maslin, panned 1Q84, dismissing it as “stupefying” and criticizing the author for leaving questions unanswered and for quirks like focusing too much on a few characters’ breasts. And what’s going on with the “Little People” in the book? They, Maslin wrote, “are supposed to be very wise, even though the smartest thing they ever say is “Ho ho.” These are fair criticisms.

“Is he the best sentence-by-sentence writer? No,” the novelist Nathaniel Rich said. He thinks Murakami is prone to writing awkward and clichéd sentences, but he loves his work regardless. “I think he’s creating something that’s new, and that doesn’t exist in the world. I think it’s an artistic endeavor. I think he’s creating art.” What he is, Rich said, is an excellent storyteller.

“Sometimes it doesn’t all add up,” the novelist Charles Baxter, who gave 1Q84 a favorable review in The New York Review of Books, said. “The work is not without its faults, but that’s part of the appeal. I have to say that I find Murakami’s failures more interesting than other people’s neat successes … He has a prodigious imagination, and he has a prodigious intelligence, and somebody like that is going to err on the side of excess.”

With Murakami, there are certain motifs that appear again and again, and for which he’s sometimes mocked—cats, wells, baseball, and jazz, to name a few. Thematically, Murakami’s work explores the complexities of relationships, sex, self-discovery, the influence of Western culture in Japan, violence, and the reverberations of World War II. “You get a sense of the oddness and the eeriness of a modern culture, I think, which was born from a great act of violence,” said John Freeman, the editor of the literary magazine Granta. “His work is full of monsters and earthquakes.” Freeman said there are two things that make it hard for Murakami to win big literary awards and gain unmitigated praise. The first is that his stories have an improvisational feel to them, even if they weren’t actually improvised. The second is that “there’s a silliness and comedy to his work, and people who have comic impulses I think are always underrated in the short term.”

Many of Murakami’s fans in Japan were disappointed when last year’s Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Chinese novelist Mo Yan. “It will be a few years before they give it to another East Asian writer,” Murakami’s translator Philip Gabriel told me. “ But I wouldn't be too surprised if he comes out on top in four to five years.” The Washington Post’s Pultizer Prize–winning book columnist Michael Dirda think that “he does have certain strikes against him.” For one, he is still relatively young. “Perhaps more of an obstacle, his books are enormously popular and readable,” Dirda said. “My guess is that the prize will come to him eventually, if he continues to produce work of a consistently high quality.”

As popular and readable as his stories are, whether someone holds Murakami’s work in high regard may depend on how much tolerance they have for events that go unexplained. David Ulin, a book critic for The Los Angeles Times, thinks Murakami uses “the particular weirdness of his stories to get at a kind of more generalized weirdness that everyone’s in touch with,” he said. “Life is weird and incomprehensible and strange things happen all this time.”

As Jonathan Franzen said, there’s a kind of “manic inventiveness” to Murakami. But that’s just one extreme in the books. The other extreme is “rooted in very quiet, quotidian, perhaps more conventionally Japanese forms of narrative.” Some of Murakami’s work, he said, is unbalanced, skewing too far toward one of the poles—the earlier stuff felt too manic—but in Wind-Up Bird, he hit the equilibrium. It comes down to the resonance he found in that book, and the reminder of the baggage that’s hidden just below the surface. “I love a psychological novel, and a novel that reproduces that sensation that the stuff I thought was behind me—none of it is behind me,” Franzen said. “There’s so much more going on in the world, and I don’t have to go outward to find it. I go inward to find it. I go down in a hole to find it.”

A version of this article originally appeared in Newsweek Japan.

Editor's note: an earlier version of this article gave the wrong name for one of the translators of Murakami's books.