I suspect AIDS, for many people under 40 in particular, is like World War II, a historical event in the hazy past, with a few heroes and many more faceless victims.

While the most significant new AIDS-related artwork of the year (and probably the decade) is Sarah Schulman’s monumental 700-page history of the plague, Let the Record Show, I spent a hot, post-pandemic Sunday at MOMA-PS1 to visit a different recollection of the plague years: the exhibit of work by ACT-UP activist Gregg Bordowitz entitled Gregg Bordowitz: I Wanna Be Well.

Schulman’s tome and Bordowitz’s retrospective are similar in some respects: both replace the myth of AIDS activism with something altogether less distant and less heroic. Schulman’s book eschews traditional, chronological history, opting instead to tell multiple, interlocking, and often contradictory narratives about the period, with the explicit intention of gathering resources for today’s young activists. Learn from us, Schulman seems to be saying (she herself was active in ACT-UP for most of its heyday), in all our messiness, brilliance, and rage.

Similarly, Bordowitz’s video work, writing, photographs, and other documentation reveal a young, gay, Jewish New Yorker who might as well have been me when I was his age, except that he caught a lethal virus in 1988 and was instantly radicalized, simply in order to survive. Bordowitz was messy, talented, uneven, and a bit of an “AIDS Diva,” as one activist describes himself. I Wanna Be Well (titled after a mediocre Ramones song) is not a heroic narrative, and definitely not a victory lap. It’s the record of someone exceedingly human.

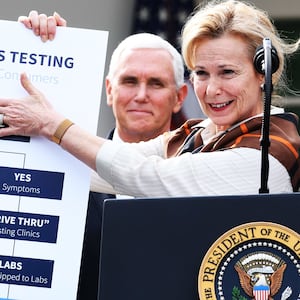

And yet, the times were extraordinary. Inevitably, seeing this show in 2021 places the AIDS epidemic alongside the COVID-19 pandemic. There are similarities: a deadly virus, a climate of fear, and Dr. Anthony Fauci (once vilified and later advised by ACT-UP, Fauci has been the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases since 1984).

But there are also some critical differences: COVID is a pandemic shared by all of us, whereas AIDS was depicted as only affecting easily marginalized “others” (gay men, Black men, drug users). People with AIDS were stigmatized, treatments took years to become available, and often, the plague was simply ignored.

By way of parallel, imagine if you and everyone you know had the coronavirus, but most people didn’t. Some of your friends had died of COVID, shamed and ostracized by their families and even some hospitals. Life as you knew it was over. And yet for most people… life just somehow seemed to go on. People didn’t talk about it. Pharmaceutical companies didn’t care. In place of the massive and historic effort that our society undertook to fight the spread of COVID and develop the most miraculous vaccines in history, imagine you’re left to your own devices, mocked, and told you deserve it.

Like many AIDS activists, Bordowitz was motivated by anger, despair, a sense of moral outrage, and sometimes all of them at once. In perhaps his best-known work, the roughly hourlong video Fast Trip, Long Drop, Bordowitz juxtaposes the personal and the political, weaving his own story in with the injustices of the AIDS crisis. The video begins with a fake newscaster telling HIV-positive people, in chirpy TV journalist voice, that there’s nothing they can do about it and they’re all going to die. But hey, the rest of us won’t.

Cut—in MTV-influenced 1990s video montage style—to Bordowitz alone in his apartment, wondering if his flu symptoms are Lyme disease or a reaction to experimental drugs or perhaps something worse. Cut again to archival footage of an old Jewish cemetery, and the grave where Bordowitz’s biological father (who he barely knew) is buried. Cut again to a support group made up of some of the central figures in ACT-UP including Peter Staley and Spencer Cox. Cut to Bordowitz reminding his mother that she cried when he came out to her.

I was struck, watching the film, by how young Bordowitz is in it (he was born in 1964; the film was released in 1993). God, these people were kids—some of them, anyway. Bordowitz sports a ’90s-era wave haircut in some scenes, a buzz cut in others. This was his youth that was taken away from him—his twenties.

And yet, Bordowitz and the other members of ACT-UP (most of whom are white and male in the exhibit; Schulman’s book struggles mightily against this presentation) somehow found a way to make change. They forced the release of experimental treatments. After they snuck into the New York Stock Exchange and called attention to the pricing of medicines (the fake ID badge that Bordowitz used is on display), the prices were lowered. They forced America to pay attention, because they knew that more silence meant more death.

They weren’t unified—Schulman highlights this as a strength, in contrast to more recent movements which require activists to stay “on message,” but Bordowitz shows how stark the disagreements could be in one hilarious video sequence parodying Larry Kramer as ‘Harry Blamer’ who only wants to complain about his own illness. I know from my friends who were active in that period just how rancorous those Monday meetings could get.

As an exhibit, much of I Wanna Be Well is uneven. One gets the sense that after the first wave of the AIDS crisis ended in 1996, with the advent of drug “cocktails,” Bordowitz lost his subject matter and his art lost its urgency. But this isn’t so; he’s only 56, and still making vital art today, including a set of acerbic “pandemic haiku” that you can download for free from MOMA, and is still very much involved in health-care activism.

Maybe it would have been better to focus exclusively on the plague years, even though, as a banner on the front of PS1 insists, the AIDS crisis is just beginning. (Indeed, the present of AIDS may look like the future of COVID, in which people with access to medical care thrive, and those without it suffer.)

Mostly, though, I was stunned by the familiarity and humanity of Bordowitz and his friends (and Long Island Jewish family). This wasn’t that long ago, after all. It wasn’t far away, either. And viewing this record of the plague as we slowly emerge from another one, one gets the sense that it could easily happen again.