The only thing I wanted during my short infamy in the blogosphere was for the noise to stop. I had broken faith with the market, and the market was seeking its revenge in the form of hundreds, even thousands of posts from angry Brooklynites.

Yes, I had gotten mugged at gunpoint, and yes, I was now talking trash about my neighborhood. But the real crime—the one that couldn’t be forgiven by the likes of New York magazine—was that I might be threatening to help push artificially elevated real-estate prices off a precipice they were nearing all by themselves. As a defamer of the market at the height of its fascist mania, I had rendered myself an enemy of the people.

I turned down an opportunity to tell my side of the story in The New York Times Week in Review. I was just too weary, and every effort to dig myself out of the hole I created just got me in deeper.

I had gotten mugged in front of my rental apartment—on Christmas Eve, no less—and had posted the time and location of my mugging to the Park Slope Parents list, a generally helpful, crunchy, and supportive message board for people raising kids in that section of Brooklyn and beyond. Within an hour, my email inbox was filling with messages from concerned neighbors. Scratch that: angry neighbors.

They wanted to know exactly why I had posted the exact location where the mugging had taken place. Didn’t I realize what this could do to their property values? No, these folks had no immediate plans to sell their homes—yet they were still more considered with the short-term asset value of their real estate than they were the long-term experiential value of their neighborhood!

I had already begun my latest book, an alternative history of the development of corporations, in which I hoped to warn people about the precarious position of our economy and the society we had built according to its very tilted ideas about debt. But this episode changed my focus entirely: I became less concerned with the way corporations acted on us than the way we had come to act like corporations, ourselves.

The reaction of a handful of Park Slope residents to a crime in their neighborhood had less to do with eradicating crime than the episode’s ability to detract from the district’s precious brand. My effort to analyze the impact of gentrification and displacement on the relationship between rich and poor was swiftly reframed as the racist outrage of a weak-kneed liberal. Or, as New York magazine put it in their headline, “Are the writers leaving Brooklyn?”

Of course, none of this happened because Park Slope’s residents or the many who jumped on the bandwagon of outrage were bad people. This was the height of a speculative frenzy, remember, when overleveraged homeowners were depending on ever-increasing prices to refinance mortgages that they would otherwise be unable to pay. Like corporations, they were responding not to their real needs or their neighborhood’s but their debt structures. In such a situation, it was the only way for humans to respond. But it wasn’t the most human response.

I turned down an opportunity to tell my side of the story in The New York Times Week in Review. I was just too weary, and every effort to dig myself out of the hole I created just got me in deeper.

Instead, I set to task to write a book that could explain how human beings had surrendered not simply to the logic of the market, but to the logic of a very specific market—one where people didn’t really own homes as much as they serviced mortgages.

It’s a market that was devised during the Renaissance, in an effort by a waning aristocracy to compete with a rising merchant class. How could they stay rich without actually creating value? How could they make money simply by having money?

They came up with two main innovations. The first was the chartered monopoly. Instead of allowing a free market to decide which company would win out, kings chartered specific companies to have total control over a given sector, be it mining for coal or colonizing America. In return for a sizable investment in the chartered corporation, the king would write laws that, for example, forbade American colonists from fabricating clothes out of the cotton they grew. They’d have to sell it to the British East India Trading Company, let it be shipped back to England where it was made into clothes before being shipped back to the colonies and sold back to the people. Laws like these were enough to foment a revolution.

The other Renaissance biggie was centralized currency. Instead of being able to generate their own currencies based on the annual harvest (which worked so well in the late Middle Ages that small towns were wealthy enough to build cathedrals as investments in the future), everyone would have to use coin of the realm: gold coins issued from a central bank. This kept the monarchy at the center of the economy, and able to drain value for itself whenever it needed to fight a war or build a new summer palace.

This all came down to us as a corporate-controlled central banking system that still works, primarily, to give a structural advantage to lenders. The stuff in our wallets and bank accounts isn’t money; it’s a kind of money, devised to favor certain behaviors. Our money is not earned but loaned into existence—at interest. As a result, we compete for scarce currencies, making “markets” out of goods and services that would otherwise be in abundance.

I came to believe that we are living according to a set of rules that we take as given circumstances, but are really nothing of the kind. And now that the debt-based, corporate-driven system is crumbling under its own weight, we spend our great-grandchildren’s tax money bailing it out instead of coming to the much more logical and fact-based conclusion that we are supporting a system that was designed less to support our economic activity than to force us into the competitive, self-interested roles we have, understandably, assumed.

And in the end, I suppose I am no better. While I would love to promote change—or at least an awareness of how we’ve gotten to this sorry state—here I am, pitching a book that I also wrote to pay the mortgage on the decidedly more modest home I bought for my family just outside the city. In doing so, I end up capitalizing on the very mugging, and after-mugging, I was hoping would just fade from the collective memory.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

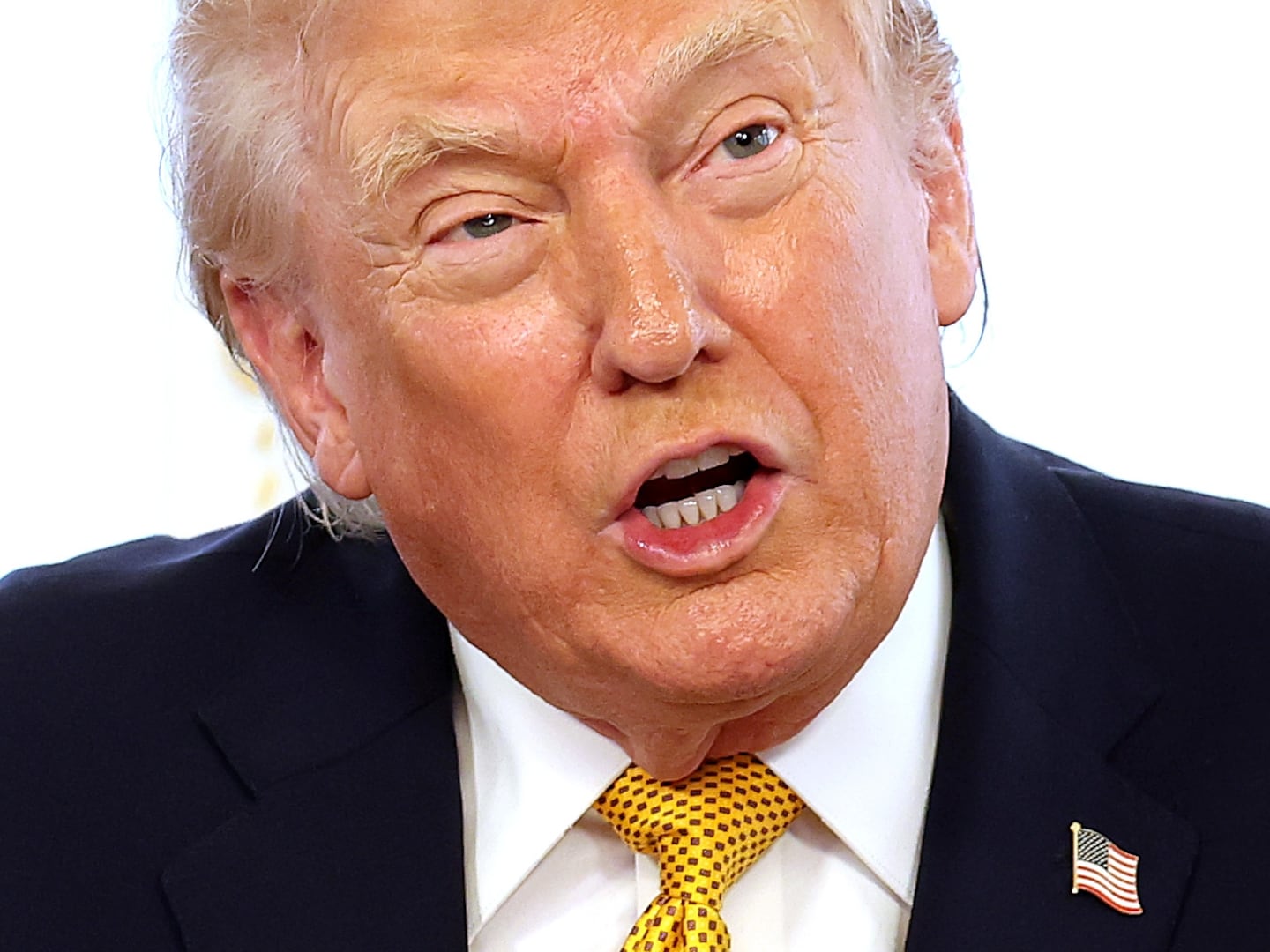

Douglas Rushkoff, a professor of media studies at The New School University and producer and correspondent for the PBS Frontline Digital Nation project, is the author of numerous books, including Cyberia, ScreenAgers, Media Virus, and, most recently, Life Inc., released this month by Random House.