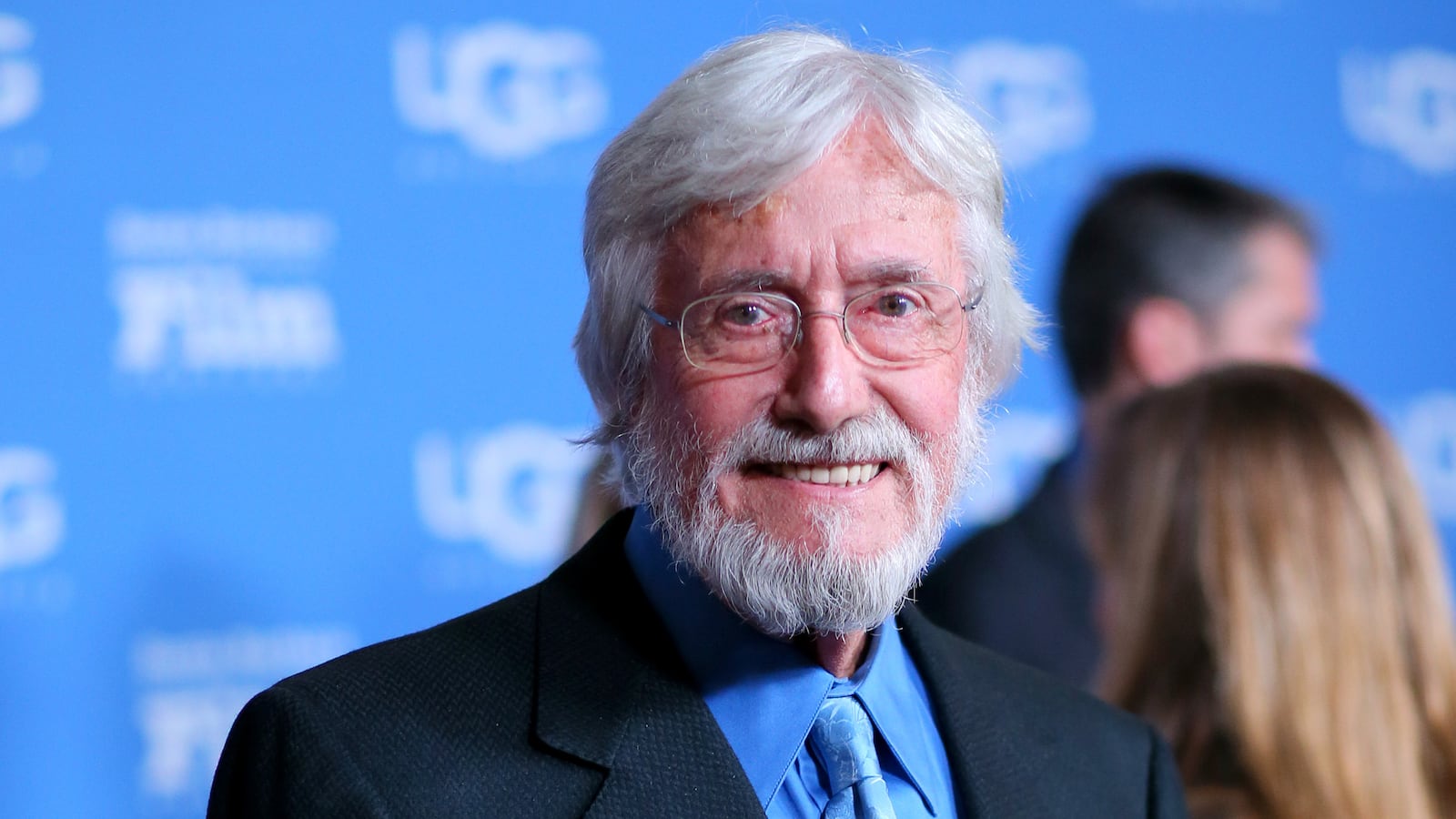

Jean-Michel Cousteau is ushered into the interiors of a smart white yacht moored in the old port of Cannes, looking a little bit dazed, like a mad professor of sorts.

“Look at this. Talking, talking, talking,” he says, affably, as he unfolds from his jacket pocket a schedule of back-to-back interviews that have taken up much of his day at the Festival de Cannes.

But help is on hand.

A server suggests a Bacardi and Coke, and he takes a gulp before turning his attention to the last interview of the day.

Call it homework, but before Cousteau, 77, arrived I had donned the requisite 3D specs and watched two trailers crafted from the 200 hours or so that Cousteau has filmed underwater for his next film, Odyssea 3D.

“My father’s film The Silent World won the Palme d'Or in Cannes in 1956. It is my dream that this film plays here next year to mark 60 years and to honor him,” he says.

Dreamy-looking creatures, some of whose skins are a bright canary yellow, others a decadent pink, peer at the camera before floating away into the background, making for mesmerizing underwater images.

New technology has allowed Cousteau and his team, which includes his son Fabien and daughter Celine, to capture minute creatures in close-up. And this he finds important.

“My father always said people care about what they know. So it is important to show them the foundations of life. We tend to focus on the bigger things, but life begins with the tiny plankton and the bigger plankton that eat them and the fish that eat them,” he says.

I have never dived, and I have also never seen anything that looks quite that sublime on screen. I feel like it’s a world I too now want to explore, like Jean-Michel.

Asked where he has come in from, Cousteau rattles off a string of countries, all of which he seems to have visited in the past week.

But as the son of the fabled diver and marine pioneer Jacques Cousteau, he prefers to spend his time underwater.

And as for how much time he spends there, he says, “A lot, but not as much as I would like. I always say my next dive is the most exciting.”

Cousteau dallied with the idea of becoming an architect and, in fact, trained to be one so that he could build underwater cities, but he started helping his father after his diving explorations began at an early age.

Somewhere at sea in the Mediterranean, he learned to dive at about the age of 7. “I was pushed overboard with new diving equipment on my back and that was that,” he recalls.

The family has dabbled in underwater dwellings, with his father building and living in the world’s first underwater habitat for 30 days. His son Fabien more recently spent 31 days underwater to beat his grandfather’s record.

And Jacques Cousteau also invented the Aqua-Lung and pioneered marine conservation.

Like father, like son, Jean-Michel is also an underwater explorer, an environmentalist, an educator and filmmaker. He is in Cannes presenting footage from Odyssea 3D, which was filmed at depths between 30 and 60 feet.

“We only know about 5 percent of what is in the ocean,” he says, expounding upon dreams to dive to 1,000 feet for his next film, stay for 10 hours, and come up in five minutes.

He lives in Santa Barbara, California, where his Ocean Futures Society is headquartered and is run by his children, who are both expedition members of the society.

But he only spends about 25 percent of his time there. For this film alone he has traveled from Fiji to the Bahamas and there is still 50 hours of filming to go, he says.

His overriding goal, he says, is to educate on the importance of the ocean. And to that end in this film, which is a tribute to his father, he wants to show tiny sea life up close.

“We are the only species with a choice,” he says. “The oceans make up 70 percent of our planet. When you ski, it is on the ocean. When you drink water, it is the ocean. But how can people care about what they don’t know?”

He is filming Odyssea 3D using revolutionary new cameras that allow these creatures to be filmed in slow motion—breaking new ground from his previous 80-plus films, many of them educational.

And he is often called in to advise top-level people, like the former U.S. president, George W. Bush.

He recalls answering dozens of questions for Bush after a White House screening of his film Voyage to Kure, which ultimately led to him making changes, declaring the 138,000 square miles of ocean around the northwestern portion of the Hawaiian Islands a Marine National Monument.

“My goal is education, education, education, and to sit down with decision-makers and not complain and teach their hearts. They have families; they care. Their goals are short-term. I want to bridge their goals with the future,” he says. “Normally, they would create a defense system. As I am not attacking them, I can get them to make decisions and correct the mistakes we are making. Bush saw this film. He was so shocked he declared those islands the biggest protected marine life on earth.”Cousteau continues, “We screened at the White House and he asked a million questions. What works is that I’m not your enemy, I’m your friend. I’m not into politics. I want to help and this approach does work.”

Cousteau knows of what he speaks and recounts amusing tales of life aboard his father’s expedition ships, Calypso and Alcyone.

He tells stories of the ship having to be rerouted to sail extravagant routes, and of carting film footage for his father’s films from the depths of South America to Los Angeles to be developed, back in the old days.

“For our dives with these cameras it is much easier,” he says. “But we still have to come up to the surface to see what material we have, so many times we go back down again and again until we have what we need.”

He talks of mythical-sounding places like Lake Titicaca on the border of Peru and Bolivia, and sailing to the Panama Canal and of his own love of the Pacific. “It is the ocean I know the least,” he says.

Much of his research is conducted through Ocean Futures Society, which the organization has dubbed the “Voice for the Ocean” with a mission of “communicating in all media the critical bond between people and the sea and the importance of wise environmental policy.”

Cousteau has dubbed himself a “diplomat for the environment.”

“I owe it to every 5-year-old to have the same privileges as me,” he says. “I’m like a kid. Every time I go diving, I see something I have not seen before.”

“I like being wet,” he quips—but not for too long. “I trained as an architect because I wanted to build underwater cities. But we are not meant to have wet skin.”