In the photograph in front of me, there is bare-chested middle-aged white guy with his arm over the shoulder of a beaming black girl, who looks quite a bit younger.

Layla Love, who shot this picture on a volcanic sand beach in Cameroon in Central Africa, knew that the guy was a German sex trafficker. She and her (hefty) driver told the girl her destination was not the banana plantation where she had been promised a job and took her back to her village.

Love was 21, and a student at the American International University in Richmond, not far from London. This shot launched her onto a pictorial investigation into human trafficking and slavery that she has been continuing ever since.

Some of what she has come up with can be seen at 'Rise,' a show of her work at 555 West 25th Street in New York City. (I am listed as a curator, rather generously, because Love did all the heavy lifting herself.)

Another picture shows four alert young women, three wearing bunny ears, standing in front of an ATM machine. Love got the shot two years ago in Tenancingo, which is a town south-west of Mexico City nicknamed “Pimp City”. “There’s a festival every year,” she said. “A parade. It’s kind of a Mardi Gras for traffickers.”

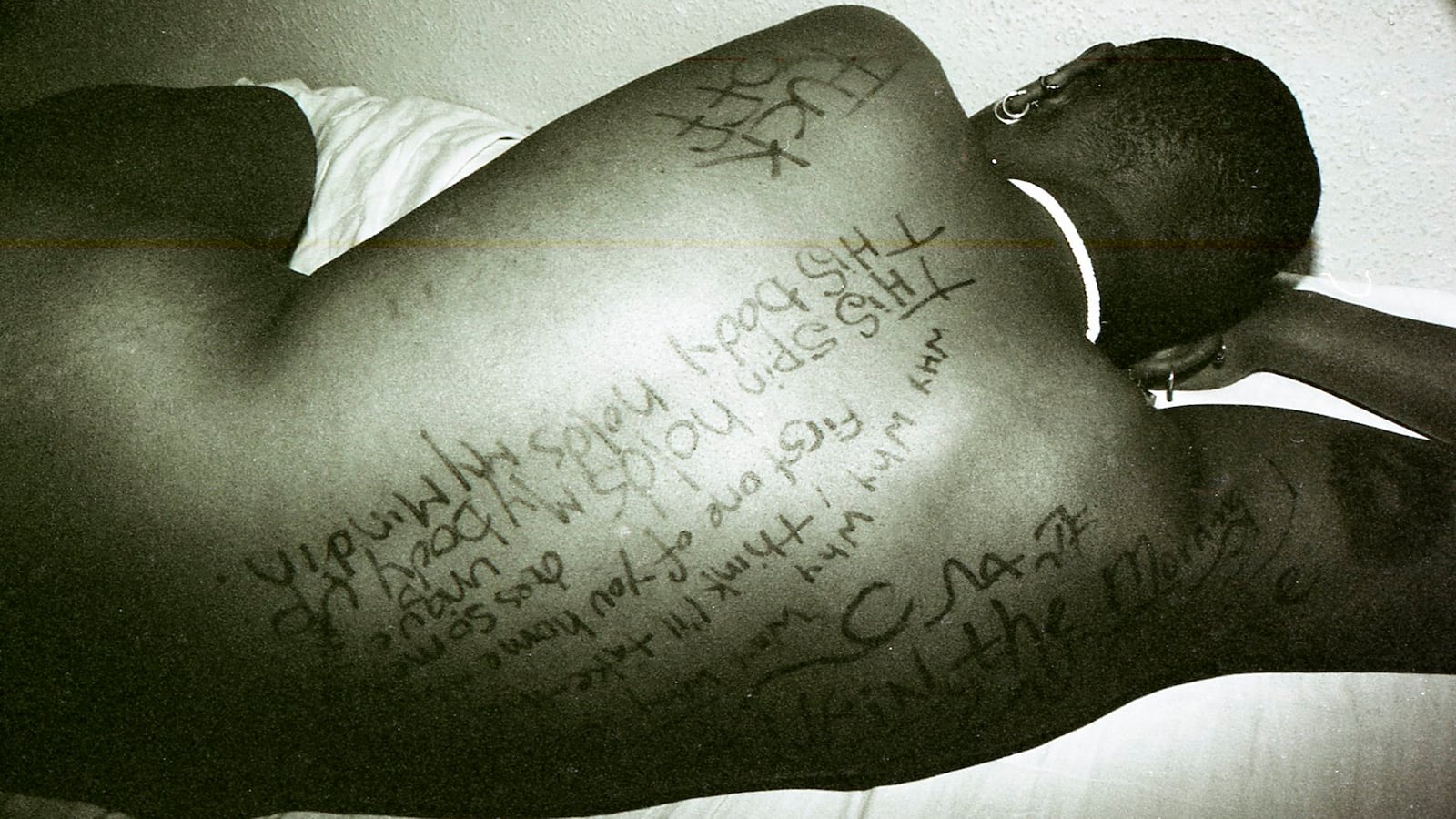

She shot the torso of a young man in a house in Bosnia, “It was all boys in there,” Love recalled. “They looked drugged. Some had lipstick on. I just walked in, looking like a lost girl, and started taking pictures.” Nobody tried to stop her.

A picture of two composed-looking young Asian women, Love said, was taken in “the Woman Love Market in Kyoto, Japan. They are locked in their rooms at night.”

Why don’t they try to escape? “The guys have guns on them. They say they’ll kill their mothers, their sisters.”

The hellish photographic tour continued. One picture showed a man sticking his arm out of a cage in Rajasthan, India.

Two tiny boys in another picture are “orphans that are being sexualized. That was in Bosnia in 2006.”

Another two infants are pictured "in a brothel in Calcutta. The mothers are prostitutes.”

An image of a horrifically sightless black woman was taken "in the south of Chad. She blinded herself. They are no use in the sex traffic in Chad if they are blind. Sometimes they blind their children too.”

“That’s labor trafficking," Love said of an image of some children. "This was in Egypt. They are put to work when they are a few years old, beating leather with chemicals to soften it in the hot sun."

What of the photograph of a young woman with the much written-upon body? “I shot that in Compton in Los Angeles County,” Love said. “She had been raped since she was seven. She was trafficked by her cousin. That was the worst story I heard.”

This is the ugliest material you can imagine, and an extremely raw and immediate form of reportage. “It’s like I’ve been studying this my whole life,” Love said. “It’s been a lifelong obsession. Like espionage. So I started a non-profit two years ago.”

It’s called The Rise of the Butterfly, but is hardly alone out there. In 2000 the UN announced a Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, which is often referred to as the Palermo Protocol, and, as of last September, 171 of the 192 member states of the UN had given it their support.

The Coalition to Abolish Slavery and Trafficking (CAST), one of a number of global NGOs who focus on the issue, state that: "Human Trafficking is the fastest growing criminal enterprise of the 21st century, an estimated $150 billion industry that is second only to drugs in terms of organized crime."

The source for their statistics is a paper published by the International Labour Organization in 2014.

Similarly, the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW) notes that human trafficking is the fastest growing criminal industry in the world. It is tied with arms trafficking as the second largest criminal industry in the world, after drug trafficking.

Other numbers are as darkly illuminating. Voices 4 Freedom, another NGO, estimates that forty million individuals were experiencing slavery on any given day in 2016, that 71 percent of them were female, and that one in four was a child.

The Global Slavery Index, an annual study published by the Walk Free Foundation, puts the 2016 total of 45.8 million people, including 57,700 in the United States.

Most studies agree that at last two thirds of the business is sexual, that it is routine for children of 12 or far younger to be swallowed into it, and that the rest is labor slavery, like those kids pounding hides in Egypt.

The first two facts in "11 Facts about trafficking," a document put out by the non profit, Do Something Org, are that 1: Globally, the average cost of a slave is $90 and 2: Trafficking primarily involves exploitation which comes in many forms, including: forcing victims into prostitution, subjecting victims to slavery or involuntary servitude and compelling victims to commit sex acts for the purpose of creating pornography.

There is not much doubt about Fact 2 but there is less agreement about Fact 1, or indeed about many of the given statistics, but this is understandable. Statistics can be variable – the price of a human being can be way higher – and, if the purported slaves are being held in the United States or Western Europe, some may ask, why they don't try to escape?

There are a slew of answers to these questions, including legal intimidation, as with undocumented immigrants, and – as with the slew of recent cases involving battered wives – insidious shackles on the mind.

“Our first problem when we started fighting slavery in 1999, 2000, was that people didn’t even believe it existed,” said Peggy Callahan, a Los Angeles based documentary film producer.

She discovered the subject by way of a book, Disposable People, by Kevin Bales. “He did all the original research,” she said. “At one point the average price of someone in slavery was $48. People have become so inexpensive that it’s horrifying.”

At the time of the slave trade destroyed by President Lincoln a human being cost the equivalent today of $40,000, Callahan said. So, it was as inhumane then as now, but clearly slave owners might be motivated to protect their capital investment. “But when people cost $90 or whatever it is, they get used up and thrown away,” Callahan said.

Callahan tracked down the Oklahoma-born Bales at the London School of Economics.

“I called him and told him we should start an international movement on slavery," Callahan said. "I don’t know if he thought I was a California fruit-loop or a godsend. I don’t know if he knows yet.”

The duo have launched two groups, Free The Slaves and Voices 4 Freedom. “I decided to go and document it in villages in countries all over the world, and then share it free of charge," said Callahan. "Because most video costs between 60 and 80 dollars a second to buy.”

At Love's show the slavery pictures are raw but there are also luminous pictures – images of recovery, life, health, pleasure.

According to the International Labour Organization statistics, there were 5.4 slaves to every 1,000 people in 2014.

“There’s more slavery in the world today than at any other time in human history,” Callahan said. “But it’s actually a smaller percentage of the population. So it’s horrifying. And yet it is actually getting better, because of all the pressures that can be put on governments and because there’s no government that relies on slavery. We actually have a shot at ending it forever.”