The catalogue to Revelations, Olivier Dassault’s show at the Marlborough Gallery at 57 West 57th Street, has a double whammy of a cover, a multiple exposure of the West Side of Manhattan, shot from the air.

This is the curtain-raiser for a show of large photographs, some of which include recognizable images – houses and cars – and some of which are pure abstractions, but also it’s a bit of a lapel-tugger, because Dassault is not only the scion of France’s most powerful aviation dynasty but himself a formidable airman.

Marcel Dassault, his grandfather, survived torture in Buchenwald, and went on to design such classic fighters as the Mystère and the Mirage.

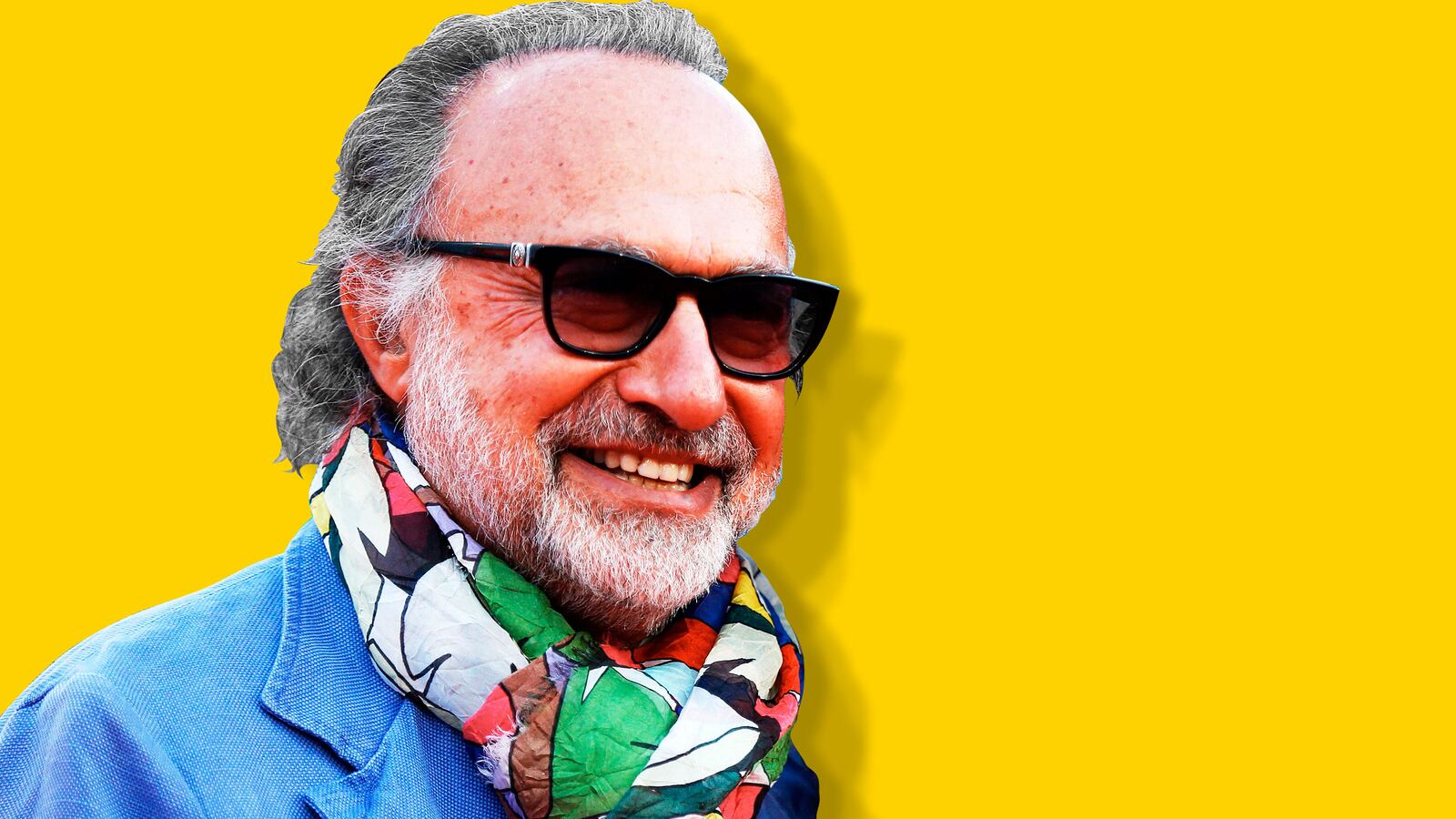

He became very wealthy and joined the Assemblée Nationale, the French parliament, being the oldest member at the time of his death in 1986. Serge, his son, continued the aviation tradition. And so did Olivier, Marcel’s grandson. “I learned to fly when I was very young,” Dassault, now 67, told me. “I could fly before I could drive a car.”

'Carré d'Or'

© Olivier Dassault and Marlborough Gallery, New YorkOlivier Dassault can now fly every type of plane the company makes and he and a co-pilot have won world flight airspeed records for the New York to Paris flight in a Dassault Falcon 50 in 1977, New Orleans to Paris in a Dassault Falcon 900 in 1987 and Paris to Abu Dhabi in a Dassault Falcon 900EX in 1996, going on to beat his own record doing the same flight in the same plane later that same year.

Photography has been an equally obsessive pursuit. Dassault was shooting well before he took to the air. “I was a child. I was nine years old,” he said. So absorbed did he become that he was thinking of taking it up as a career, an ambition his family did not encourage, and he too came to see certain disadvantages.

“I realized I would have to do advertising photography. Or reportage,” he said. “If I was within the company, the family, I would be more free to do art.” That decision was taken when he was twenty.

Dassault got a Bachelor’s degree in Engineering at the École de l’air, France’s Air School, and graduated as a combat engineering officer/pilot in 1974. He followed up by getting a Master’s in Decision Theory Mathematics and a Doctorate in Computer Science Management and went into the family firm, the Dassault Group, in which he is now president of an advisory board on development.

Olivier went on to both his feats in aviation and to follow his grandfather into the French parliament. But making pictures continued to devour him. And he always used the same camera, a Minolta XD7.

“You know, when you use something and it works well, it becomes like a friend. You are so well used to it that you don’t think any more about the taking. I use it like a painter uses a brush,” he said.

He had indeed also made paintings when young but he gave that up at fifteen to concentrate wholly on photography for what seemed to him the most commonsensical of reasons. Painting was so … slowww. “It takes too long to realize,” he said. “In the time you need to make a picture with paint I can make twenty photos.”

'Metropolis'

© Olivier Dassault and Marlborough Gallery, New YorkThat speed factor also played into his photographic development. His earliest work had inclined to realism.

Olivier shot in the city streets in Australia and Egypt – the Egypt pictures became a book, one of his many – but from very early he was working in the tradition of the manipulated photograph. “I took a cab in New York, a yellow cab … and the yellow cab seems to come out of the wall,” he said. “That was in 1976. I would put people into a wall. At this time there were no computers, no Photoshop. I did it all by double exposure.”

'Parabole'

© Olivier Dassault and Marlborough Gallery, New YorkHis purely figurative work included portraits of such young female powerhouses of the 1980s as Isabelle Huppert, Isabelle Adjani and Jane Birkin, whose fame survives in the form of a handbag.

“After the photo classic there was a time when I dedicated myself to working in the manner of the French Impressionists, like Renoir,” Dassault said. “And I made photographs that were flou.” A splendid word, meaning fluid, blurry, imprecise, Impressionist.

Again it was down to speed. Dassault believes his camera of choice, the Minolta, made his art career possible. “You know a photographer lives many lives of a painter because creation is so quick,” he said. “Then I made all sorts of Surrealistic work, and Symbolist.”

Olivier threw in a few more Isms, before bringing up a jarring moment. “I liked to take pictures of people walking in the street,” he said. Then somebody more or less accused him of copying another photographer. “I say that is the last time anybody will say I copy somebody I don’t know.” So Dassault’s last move was into Abstraction, usually visibly reality-based. And this, I observed, brings to mind the most speed-obsessed Ism of all: Futurism.

“Yes,” he said. “For example for many years I took pictures from the cockpit, which is much better than the window of the passenger. I took pictures of clouds, skies. And I made a book, Sky. Thirty years of pictures of the sky. The subtitle of the book was "The Sky Seen From The Sky.”

His flight experience is basic raw material, his version of Monet’s "Haystacks." “But from the air when you are high, you shoot the sky, the clouds. I shoot the light behind the clouds. And the sunset, the sunrise. And en route to New York I shoot the icebergs in the ocean.”

From what height do you shoot the icebergs?

“It is quite high. Forty thousand feet.”

What is the lowest you have ever shot?

“The lowest is in a helicopter, not a plane. The lowest is I’m not sure what. One hundred meters?”

In the lives of most artists, we don’t really need to know their day jobs, I said. In his case there is a direct connection. Just as it’s important to know that Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, author of Wind, Sand and Stars and The Little Prince was a flyer.

“Yes, yes, yes! Of course!” he said. But it’s not speed alone. “My secret is light. It can be something in the street. It can be a paper on the wall,” he said.

“Today we had lunch at the Greek restaurant, Abra. And it is good that I had my cameras with me. The weather was not so good at lunch. And suddenly there was sunlight. There was a green curtain on the window. And the reflection was a little blue. And I didn’t have to move from my chair. I made an abstraction.”

'Subversion'

© Olivier Dassault and Marlborough Gallery, New YorkAnd most especially this is true in the air.

“The light up there, it is very fast,” Olivier said. “And when you take a picture it is moving very quick. But the picture, it is not an accident. It is not chance. Of course!”