As AI-generated content proliferates online and clutters social media feeds, you may have noticed more images cropping up that invoke the uncanny valley effect—relatively normal scenes that also carry surreal details like excess fingers or gibberish words.

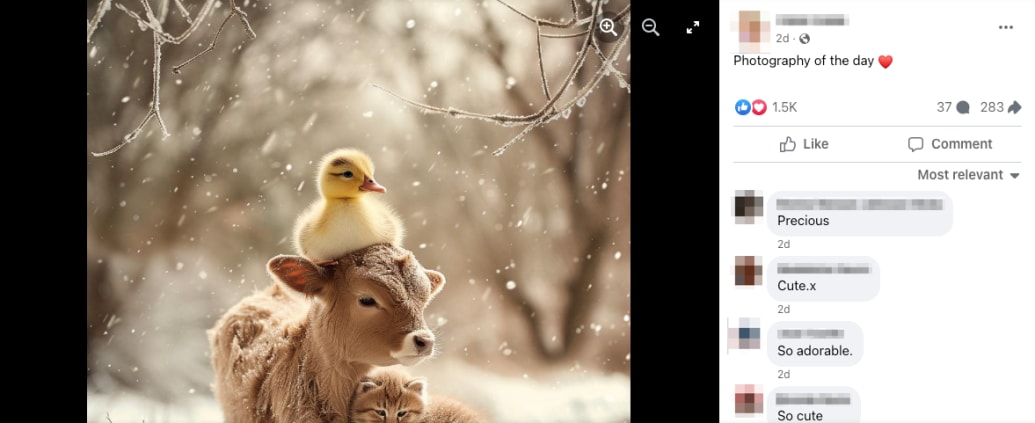

Among these misleading posts, young users have spotted some obviously faux images (for example, skiing dogs and toddlers, baffling "hand-carved" ice sculptures and massive crocheted cats). But AI-made art isn’t evident to everyone: It seems that older users—generally those in Generation X and above—are falling for these visuals en masse on social media. It’s not just evidenced by TikTok videos and a cursory glance at your mom’s Facebook activity either—there’s data behind it.

This platform has become increasingly popular with seniors to find entertainment and companionship as younger users have departed for flashier apps like TikTok and Instagram. Recently, Facebook’s algorithm seems to be pushing wacky AI images on users’ feeds to sell products and amass followings, according to a preprint paper announced on March 18 from researchers at Stanford University and Georgetown University.

Take a look at the comment section of any of these AI-generated photos and you’ll find them filled with older users commenting that they’re “beautiful” or “amazing,” often adorning these posts with heart and prayer emojis. Why do older adults not only fall for these pages—but seem to enjoy them?

Right now, scientists don’t have definitive answers on the psychological impacts of AI art because generators like DALL-E, Midjourney, and Adobe Firefly—which run on artificial intelligence models trained on up to millions of images—have only become publicly available over the last two years.

But experts do have a hunch—and it’s not as simple an explanation as you might expect. Still, knowing why older friends and relatives may get confused can offer clues to prevent them from falling victim to scams or harmful misinformation.

Why AI Images Trick Older Adults

Cracking this code is particularly important because tech companies like Google tend to overlook older users during internal testing, Björn Herrmann, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Toronto who studies the impact of aging on communication, told The Daily Beast.

“Often in these kinds of spaces, things get pushed forward not really with an aging perspective in mind,” he said.

While cognitive decline might seem like a reasonable explanation for this machine-powered mismatch, early research suggests that a lack of experience and familiarity with AI could help explain the comprehension gap between younger and older audiences. For instance, in an August 2023 AARP and NORC survey of nearly 1,300 US adults aged 50 and older, only 17 percent of participants said they have read or heard “a lot” about AI.

So far, the few experiments to analyze seniors’ AI perception seem to align with the Facebook phenomenon. In a study published last month in the journal Scientific Reports, scientists showed 201 participants a mix of AI- and human-generated images and gauged their responses based on factors like age, gender, and attitudes toward technology. The team found that the older participants were more likely to believe that AI-generated images were made by humans.

Screenshot from Facebook

“This is something I think nobody else has found before, but I don’t know exactly how to interpret it,” study author Simone Grassini, a psychologist at the University of Bergen in Norway, told The Daily Beast.

While overall research on people’s perception of AI-generated content is scarce, researchers have found similar results with AI-made audio. Last year, the University of Toronto’s Björn Herrmann reported that older subjects had a lower ability to discriminate between human- and AI-generated speech compared to younger subjects.

“I didn’t really expect it,” he said, since the purpose of the experiment was to determine whether AI speech could be used to study how older people perceive sounds among background noise.

Overall, Grassini thinks any type of AI-generated media—whether it be audio, video, or still images—may more easily trick older viewers through a broader “blanket effect.” Both Herrmann and Grassini suggest that older generations may not learn about the hallmarks of AI-generated content and encounter it as much in their daily lives, leaving them more vulnerable when it pops up on their screens. Cognitive decline and hearing loss (in the case of audio) may play a role, but Grassini still observed the effect in people in their late forties and early fifties.

Plus, younger people have grown up in the era of online misinformation and are accustomed to doctored photos and videos, Grassini added. “We have been living in a society that is constantly becoming more and more fake.”

How to Help Friends and Relatives Spot Bots

Despite challenges in recognizing fake content as it piles up online, older people generally have a clear view of the bigger picture. In fact, they may recognize the hazards of AI-powered content more commonly than those in younger generations.

A 2023 MITRE-Harris Poll survey of more than 2,000 people indicated that a higher portion of Baby Boomers and Gen X participants worry about the consequences of deepfakes versus Gen Z and Millennial participants. Older age groups had higher portions of participants calling for AI technology regulation and more investment from the tech industry to protect the public.

Research has also demonstrated that older adults may more accurately distinguish false headlines and stories than younger adults, or at least spot it at comparable rates. Older adults also tend to consume more news than their younger peers and may have accumulated lots of knowledge on particular subjects over their lifetimes, making it harder to fool them.

“The context of the content is really important,” Andrea Hickerson, dean in the School of Journalism and New Media at the University of Mississippi who has studied cyberattacks on seniors and deepfake detection, told The Daily Beast. “If it’s a subject matter that anybody might know more about, older adult or not, you are going to bring your competence to viewing that information.”

Screenshot from Facebook

Regardless, scammers have wielded increasingly sophisticated generative AI tools to go after older adults. They can use deepfake audio and images sourced from social media to pretend to be a grandchild calling from jail for bail money, or even falsify a relative’s appearance on a video call.

Fake video, audio, and images could also influence older voters ahead of elections. This may be particularly harmful because people in their fifties and above tend to make up the majority of all U.S. voters.

To help the older people in your life, Hickerson said it’s important to spread awareness of generative AI and the risks it can create online. You can start by educating them on telltale signs of faux images, such as overly smooth textures, odd-looking teeth or perfectly repeating patterns in backgrounds.

She adds that we can clarify what we know—and don’t know—about social media algorithms and the ways they target older people. It’s also helpful to clarify that misinformation can even come from friends and loved ones. “We need to convince people that it’s okay to trust Aunt Betty and not her content,” she said.

Nobody’s Safe

But as deepfakes and other AI creations grow more advanced by the day, it may become difficult for even the most knowledgeable tech experts to spot them. Even if you think of yourself as particularly savvy, these models can already stump you. The website This Person Does Not Exist offers scary-convincing photos of faux AI faces that may not always carry subtle traces of their computer origins.

And although researchers and tech companies have created algorithms to automatically detect fake media, they can’t work with 100 percent accuracy—and rapidly evolving generative AI models will eventually outsmart them. (For example, Midjourney long struggled to create realistic hands before it wised up in a new version released last spring.)

To combat the rising wave of imperceptible fake content and its social consequences, Hickerson said regulation and corporate accountability are key. As of last week, there are more than 50 bills across 30 states aimed to clamp down on deepfake risks. And since the beginning of 2024, Congress has introduced a flurry of bills to address deepfakes.

“It really gets down to regulation and responsibility,” Hickerson said. “We need to have a more public conversation about that—including all generations.”