Of all the states you might have expected to pull off an exemplary Affordable Care Act rollout led by a passionate governor, Kentucky was not the one. It is best known for bourbon and horse-racing, Republican senators Mitch McConnell and Rand Paul, coal mining. and Appalachian poverty.

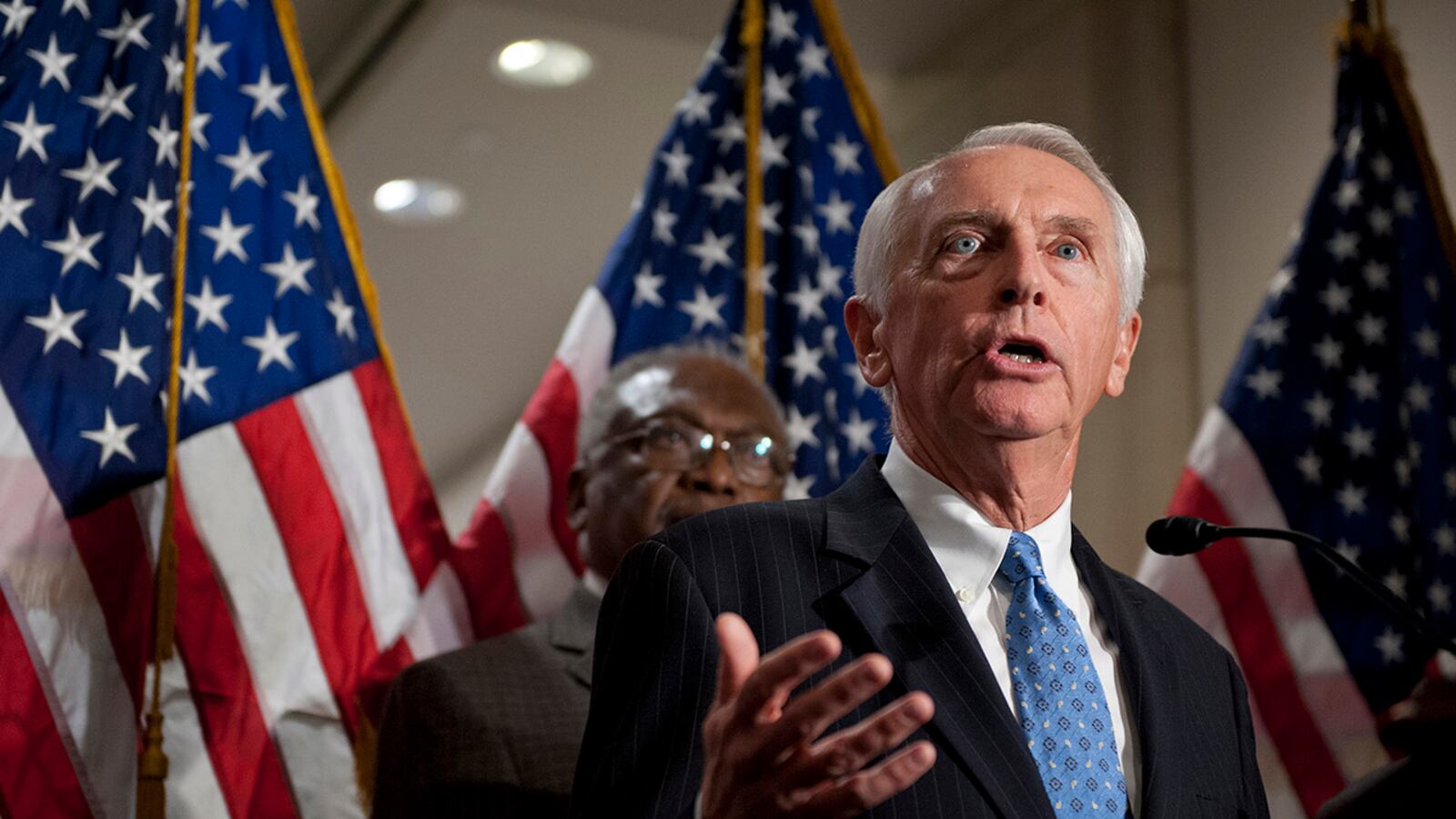

The improbability of Kentucky’s Obamacare success is a key factor in why Gov. Steve Beshear has emerged as what you might call the Democrat whisperer. Reassurances and success stories mean a lot when they’re coming from a Southern Democrat who took on McConnell, Paul, and Kentucky’s conservative establishment to seize what he calls a transformative opportunity.

“It’s probably the most important decision I will get to make as governor because of the long-term impact it will have,” Beshear, 69, told The Daily Beast during a capital victory lap this week that put him before several media outlets and some 90 members of the House Democratic Caucus. “You may not see a change next week or next month or even five years from now, but over the course of the next generation … you’re going to see a sea change in the health status of Kentuckians.”

Beshear’s confidence in the law and willingness to take the long view are bracing for Democrats, and he insists they are not due to his status as a second-term governor barred by law from serving longer. He says he’d be making the same choices even if he were running again, and does not expect his Obamacare mission to affect his son’s 2015 race for attorney general.

By all accounts, and judging by Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi’s beaming face as Beshear addressed reporters after the caucus meeting, the governor’s closed-door talk to the House Democrats was balm for the nerves of those who, unlike Beshear, will be waging campaigns next year. “My message was, take a deep breath and be patient because the Affordable Care Act is going to work. It’s working in Kentucky,” he recounted in an interview.

He predicts the impact of the issue will be neutral to positive by November 2014, and says McConnell’s ceaseless criticism of the law could end up helping Democratic challenger Alison Grimes, the secretary of state. Nor can it hurt Grimes that Beshear’s management of Kynect—keeping it simple, putting a single contractor in charge, staying involved in all decisions—resulted in a debut so smooth that other states are seeking advice from those who made it happen.

The numbers as of Dec. 5 bear out Beshear’s assertion that the law is working in Kentucky: More than 560,000 unique visitors to the site, Kynect. Nearly 55,000 people enrolled in Medicaid and more than 14,000 in private health plans. Nearly one-third of new enrollees aged 18 to 34. Nearly 1,100 small businesses starting applications for employee coverage. More than 181,000 calls made to a contact center.

Beshear says facts like these will create pressure on other states to expand Medicaid and ultimately will trump what he calls an avalanche of misinformation from critics like McConnell and Paul. “They keep saying over and over that Kentuckians don’t want this and that’s simply not the case. They need to come and look at what’s happening there,” he says.

The Kentucky Farm Bureau ham breakfast in August, where Beshear made a from-the-heart pitch for the new law that didn’t spare McConnell or Paul, both sitting at the head table with him, marked Beshear’s debut as a prime promoter of the Affordable Care Act, which is what he always calls it. He is hoping his turn in the national spotlight will allow him to showcase aspects of Kentucky that counter the image created by its high-profile conservative senators. Among them: It was the first state in the nation to adopt the Common Core education standards and is the only Southern state to both expand Medicaid and build its own exchange. “Kentucky is a progressive state!” he says.

Yet not all the publicity counters stereotypes. One Washington Post story about people signing up for health care in poverty-stricken Breathitt County included a woman with 11 children, a man who needed all his teeth pulled, a man with cirrhosis, and many heavy smokers. “I’m sure that day was reflective of a lot of people who have never had health care before,” Beshear said, adding that health in such areas will gradually improve due to the new emphasis on wellness, prevention, and educating people about smoking and management of chronic conditions like diabetes. He also noted that there are all kinds of people signing up all over the state – including a stagehand in Louisville and a part-time teacher raising two children by herself.

There is little love for President Obama in Kentucky – two-thirds in an October poll () had unfavorable views of both him and “Obamacare.” But Beshear, while taking care to point out that he is fighting with the administration over coal regulation, is not striving for distance. He is well aware that the Affordable Care Act passed at such cost to Obama will allow Beshear to create a game-changing legacy in Kentucky. “He’s done a good job in many ways,” Beshear says of Obama. “And this is certainly one of the best things that he has done.”