This week, the federal appeals court in Massachusetts unanimously ruled that part of the Defense of Marriage Act is unconstitutional. Gill v. OPM is a remarkable ruling, but perhaps as important as the decision is its timing: the court struck down a law of Congress a mere 16 years after it was passed.

Certainly no one ever thought of challenging the constitutionality of the Defense of Marriage Act in 1996! What happened?

What the Los Angeles Times recently called “the Fastest of All Civil Rights Movements” happened. And the paper wrote that headline before the First Circuit ruled. Maybe something about the president of the United States endorsing same-sex marriage inspired the L.A. Times to note the speed of the social change.

As progressive movements of every stripe falter and grind to a halt—who’s occupying Occupy Wall Street these days?—it pays to pay attention to how the gay movement broke the spell of right-wing triumph and progressive tragedy.

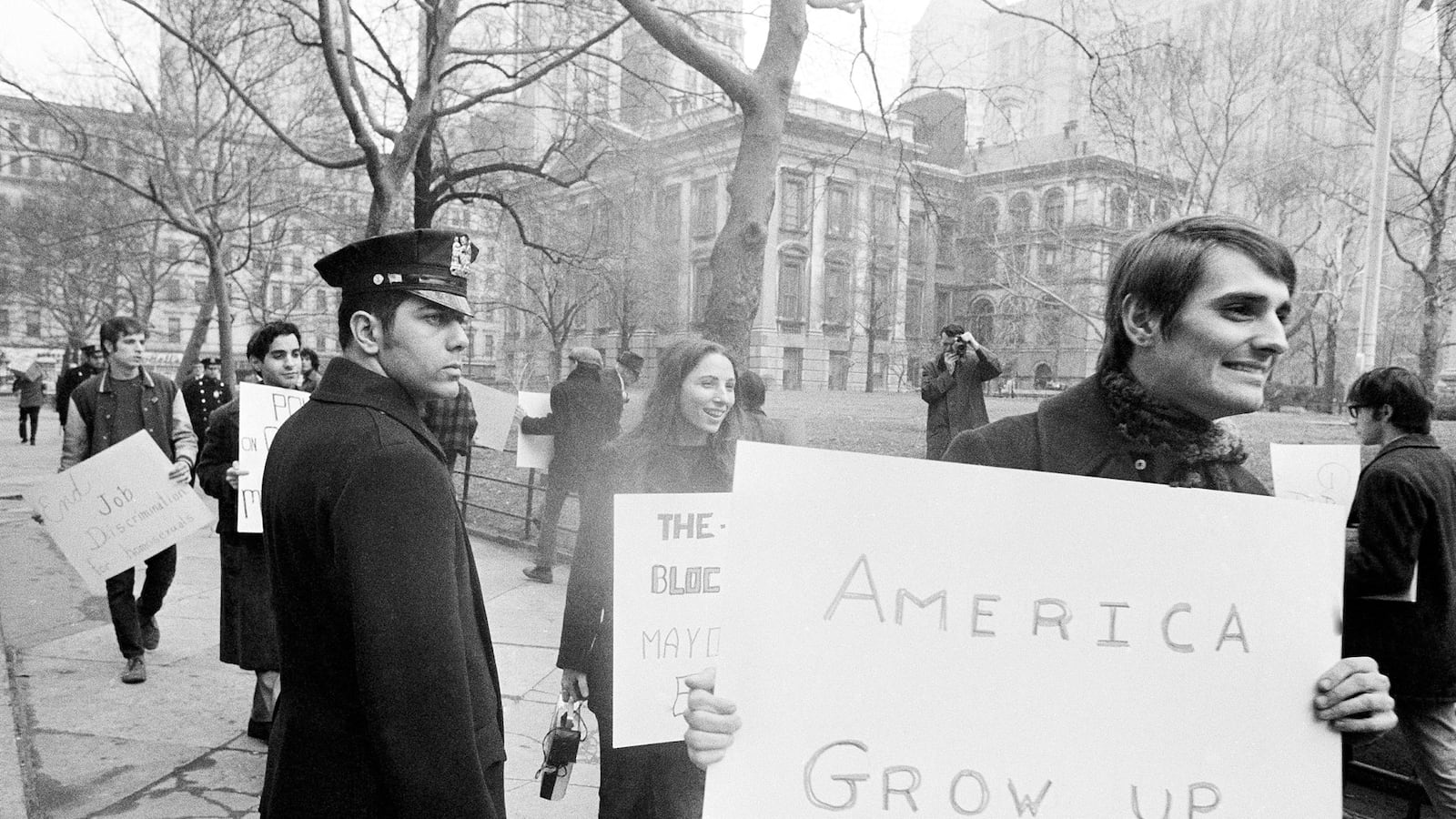

First, the movement acted locally. Local action is a gay tradition. In 1953 the Mattachine Society, the first modern gay organization in the country had the effrontery to send a questionnaire to all the candidates for the Los Angeles City Council, demanding to know their position on issues like police harassment. After Stonewall, the Gay Activists Alliance opened the modern gay movement by attacking the mayor of New York, John Lindsay, whose police had triggered the Stonewall uprising in the first place. They asked their hometown, New York, to pass a law barring discrimination against them. Gay activism has always worked from the cities and hospitable states outward. National initiatives, by contrast, were seen as losing propositions, and when undertaken, they usually did lose.

So the gay-marriage movement undertook a self-conscious strategy to start to legalize marriage more locally, in states like Massachusetts, where they had already gained traction. When the Massachusetts Supreme Court became the first in the country to legalize same-sex marriage, it was not an accident: the smart folks at the gay-movement legal organizations like Lambda Legal and Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders had seen that gay and lesbian people had gained most of the rights of citizenship in Massachusetts already.

In fact, it was the early success of another local effort on gay marriage that led to the federal DOMA to begin with. In the early 1990s, the Hawaii state courts ruled in favor of same-sex marriage, terrifying the homophobes in Congress with the prospect that the gay go-local strategy on marriage might take hold. (State referendums later overturned those decisions.) So they passed the DOMA to stop the federal government from recognizing state law on marriage. It was an unusual step—a first, in fact—to involve the federal government in what had always been state prerogative. The First Circuit rightly concluded that Congress was acting weirdly when it passed the DOMA and that something ugly, like a pure dislike of a vulnerable minority, must have been driving the legislation. Given the federal structure of the United States, in which decisions about things like marriage are overwhelmingly governed by the states, the gay act-local strategy worked perfectly.

The second secret of the gay revolution is to act as though they were good. “Why do you hate us?” their lawsuits always ask. “All we want to do is love each other.” Since the first big gay victory in Romer v. Evans in 1996, a case heavily cited and relied on in the First Circuit decision, the gay movement has not asked Americans to hold their noses and tolerate behavior they hate in the interest of freedom for all. Rather, they asked the courts to rule that hatred is in effect not allowed in the legislative process. And that’s exactly what the Romer court said: if the plaintiffs can prove, as the First Circuit said they did yesterday, that Congress acted out of animus, the law is no good.

The third secret of the gay revolution is the deep, disciplined structure of the movement. Sure, once in a while something—a riot at a gay bar, maybe—erupts. But the real progress of the fastest movement has depended on the slowest process. Lambda Legal has existed since 1973. GLAD, which won the case yesterday, since 1978. The lawyers at the National Center for Lesbian Rights in California have been working for decades. Evan Wolfson, the genius behind the slow Freedom to Marry movement, has been working on the issue since he was a law student in 1983. Andrew Sullivan’s extended intellectual defense of marriage, Virtually Normal, appeared in the mid-1990s. After the DOMA, the gay establishment met and strategized at length about where and how a locally based marriage initiative should be pursued. They did not control the world (contrary to conservative belief), but they did manage, quietly and determinedly, to enact their strategy to the decision they achieved this week.

Is it always brightest before the dark? Certainly the Supreme Court of the United States could reverse the First Circuit, ruling that even the narrowest of inroads on the anti-gay-marriage position is too liberal. But if any case stands a chance, it’s this one. Local, moral, prudent, and filled with lawyers, it’s a movement any Jewish grandmother could love. Including this one.