On Saturday, August 26, thousands of people will gather at the Lincoln Memorial to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://nationalactionnetwork.salsalabs.org/60thmarchonwashington/index.html__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUWBcPC78$">March on Washington. While the historic event was dedicated to the quest for jobs and freedom, the theme for this rally is “against hate and for civil rights.”

The march is sponsored by a diverse array of civil rights groups)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://support.adl.org/event/2023-adl-march-on-washington/e496657__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUDZajrF4$">civil rights groups, including the NAACP, one of the organizers of the 1963 march. By and large, however, the event is the work of the MSNBC host Al Sharpton—who may hold the record for staging the most rallies in the name of the iconic event.

Since at least 2000, Sharpton has been involved in high-profile marches that draw on the memory and substance of the original one. In August 2000, on the 37th anniversary, he led the “Redeem the Dream)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://nypost.com/2000/05/25/rev-al-mlk-son-plan-d-c-rally/__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NU2G-NJyg$">“Redeem the Dream” rally at the National Mall against police use of excessive force.

In December 2014, on the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, it was the “Justice for All”)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/14/us/thousands-march-in-washington-to-protest-deaths-by-police.html__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUkyzT-xc$">“Justice for All” march at the National Mall to protest police killings. In January 2017, it was the “We Shall Not Be Moved”)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://religionnews.com/2017/01/14/we-shall-not-be-moved-marchers-honor-king-fight-fear-of-trump/__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUhJOZPGE$">“We Shall Not Be Moved” march at the Martin Luther King Memorial to protest the inauguration of Donald Trump. And in August 2020, on the 57th anniversary of the march, he led the “Get Your Knee Off Our Necks”)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/08/25/march-on-washington-thousands-gather-friday-racial-justice/3337657001/__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUg3m2bhQ$">“Get Your Knee Off Our Necks” protest at the Lincoln Memorial against police brutality and for voting rights.

Students of Black political history may reasonably question whether Alfred Charles Sharpton, Jr.)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/sharpton-alfred-charles-al-1954/__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NU-JmOwZ0$">Alfred Charles Sharpton, Jr. has turned the iconic 1963 march into a side hustle?

Understand that the Brooklynite’s public career is the stuff of urban political legend. Despite numerous failed election bids for New York mayor, senator, and president, the media-savvy Sharpton has held sway over American political culture.

With his National Action Network)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://nationalactionnetwork.net/about/__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUsjgxfeY$">National Action Network (NAN), a community organization and fundraising arm, Sharpton has reinvented himself as a minister, civil rights activist, New York ward boss, and vote wrangler for the left wing of the Democratic Party. He has been a fearless critic of police brutality.

Sharpton’s model of protest politics harkens back to the days of the storefront Pentecostal ministers who represented their flock to the Boss Man. The model was prominent until the 1970s, when the Voting Rights Act gained traction, and the Black community placed its trust in a new class of elected, appointed, and accountable representatives.

Regardless, Sharpton has held the stage with a mastery of political theater, learning from a 1969 Chicago mentor, the Rev. Jesse Jackson. (That’s when Sharpton was chosen by Jackson as a youth director for the SCLC’s anti-poverty program, Operation Breadbasket).

Still, his methods have sometimes been met with skepticism, especially when one considers the historic legislative achievements of the 1963 march organizers. Compared to the earlier movements, Sharpton’s work has put forth little of lasting value in either law or institutional reforms.

Now, on the 60th anniversary, he is scheduled to lead yet another March on Washington against hate and for civil rights. The question for national Black political leadership is how to rescue the symbol of the march from the same old outcome?

What a Successful Civil Rights Protest Movement Looks Like

The 1963 march was an outstanding example of the politics of protest in the American experience. It was directed by a class of activist ministers who led a network of congregants on a crusade for racial justice. It was renowned for the sheer size and diversity of participants, complexity of organization, and success in pressuring Congress to pass the monumental 1964 Civil Rights Act)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/civil-rights-act__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUll4sIwU$">1964 Civil Rights Act.

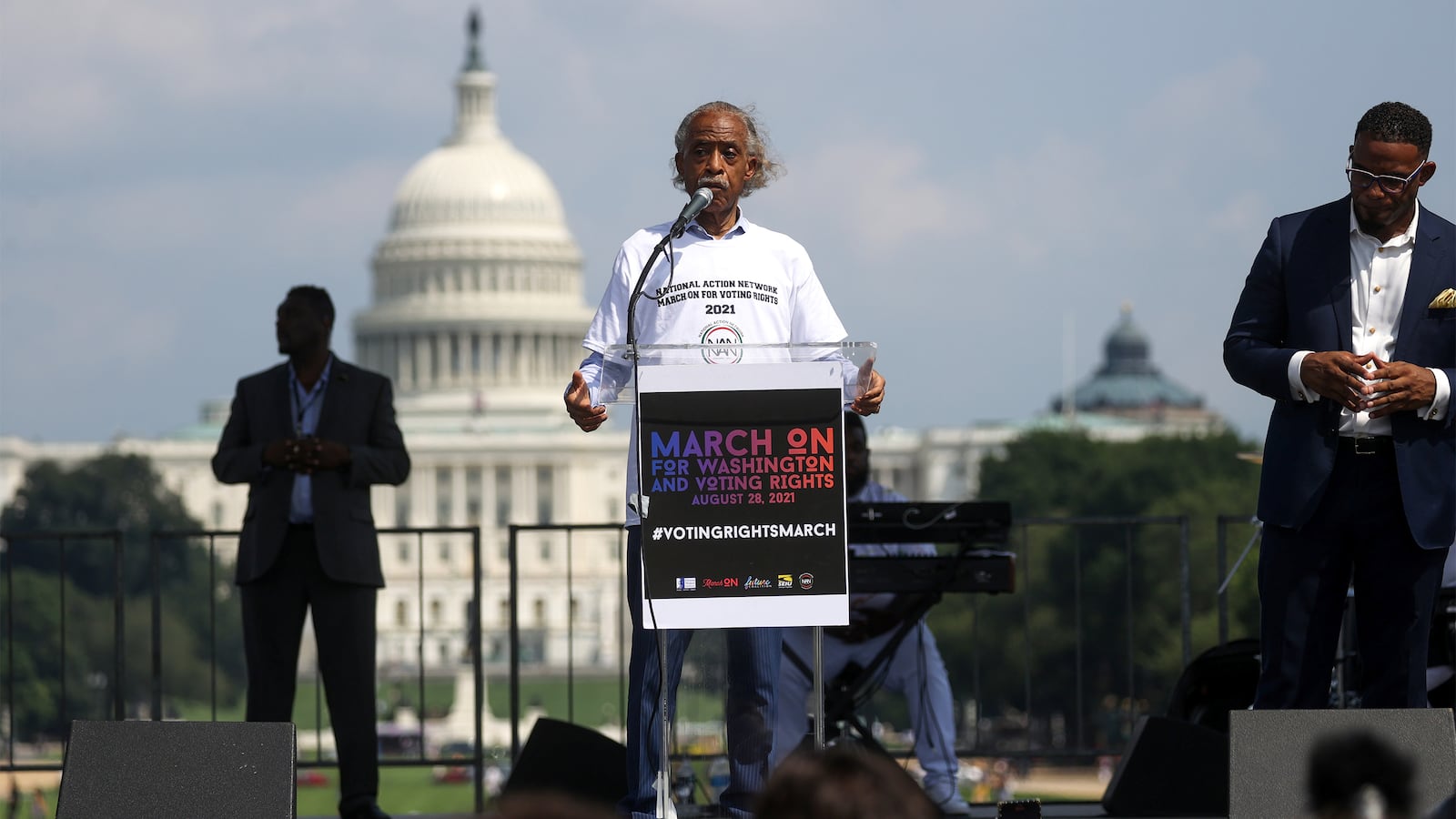

Rev. Al Sharpton addresses the "Get Your Knee Off Our Necks" Commitment March on Washington 2020 in Washington, DC, on Aug 28, 2020.

Tom Brenner/ReuteresIt took place in a climate of street battles in the South, demands on unions and employers in the North, and challenges to Jim Crow laws across the country. The most compelling was the confrontation in Birmingham, Alabama, against the many structures of white supremacy. Led by courageous Baptist ministers, the people engaged in organized acts of demonstrations, pickets, boycotts, sit-ins, and jail cell occupations.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://nationalactionnetwork.net/about/__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUsjgxfeY$">“Letter from a Birmingham Jail” explained the cause in ways that captured the imagination of oppressed peoples around the world—and the attention of President John F. Kennedy. JFK was compelled to support the cause of civil rights in a televised address to the nation. He deemed it a “moral crisis as a country” and sent Congress the strongest civil rights bill in American history.

Civil rights leaders, in a strategy to put pressure on Congress, organized a March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on Aug. 26, 1963. The coalition of organizations)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/march-washington-jobs-and-freedom__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUyw2nIDo$">coalition of organizations included King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the NAACP, the National Urban League, the Congress of Racial Equality, and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee.

More than 250,000 people responded to the call—among the largest turnouts in the history of American demonstrations. This was the heyday of the Black ministerial-led protest model. The outpouring of support forced Congress to pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act, followed shortly thereafter by the 1965 Voting Rights Act)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/voting-rights-act__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUis_gS7Q$">1965 Voting Rights Act.

The federal laws shook the foundation of Jim Crow society. However, the model of protest politics would never again reach such heights in reshaping American law and institutional practices. (Its final achievement was the 1968 Fair Housing Act)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.justice.gov/crt/fair-housing-act-1__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUJKrsITQ$">1968 Fair Housing Act.)

The Need for a “Black Agenda” Summit

Historians note that the 1964 Civil Rights Act was most successful in eradicating the egregious forms of segregation in public accommodations, but less effective in other areas of life, such as public education and employment opportunities, according to findings in Legacies of the 1964 Civil Rights Act: Race, Ethnicity, and Politics.

Perhaps nowhere were the hopes of 1963 organizers dashed than in the quest for economic justice. Such was the conclusion of “The Unfinished March)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.epi.org/unfinished-march/__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NU1QSDYN8$">The Unfinished March,” a 2013 study by the Economic Policy Institute on the outcomes of the protest.

Historian Thomas Sugrue)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.epi.org/unfinished-march/__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NU1QSDYN8$">Historian Thomas Sugrue wrote: “The loss of jobs arising from automation, urban disinvestment, capital flight, and changing population patterns was especially devastating for black workers—and the speakers at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom emphasized the point.”

Signs carried by marchers during the March on Washington in 1963.

Marion Trikosko/Library of CongressMovement leaders discussed prospects for structural reforms like higher minimum wages, federal job creation, a guaranteed income for poor families, and vast investments in urban slums, public schools, and infrastructure. Little of it came to pass. Today, many of the indicators of economic inequality used in 1963 still persist, such as Black unemployment)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://nationalequityatlas.org/indicators/Unemployment__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NU1msClXA$">Black unemployment being twice or more the level of white unemployment.

The upcoming march can serve as a bridge to the unfinished work in economic justice, if leaders have the political will? To be clear, the Black community needs leaders interested in strategies other than non-economic civil rights—and mobilizing people every four years to support the Democratic Party candidates.

What is required is a Black political unity summit on how to help people survive the challenges of the 21st century. The gathering should seek to devise a constructive agenda to finish the economic dreams of the 1963 march. But who has the standing to issue the call?

One answer may lie in the Congressional Black Caucus)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://cbc.house.gov/about/__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUEPL6B_w$">Congressional Black Caucus. This body is in a position to call for a political unity summit and is scheduled to host the 52nd Annual Legislative Conference)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.cbcfinc.org/event/annual-legislative-conference/__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUYetkh_Y$">52nd Annual Legislative Conference in Washington, D.C., next month.

The summit would allow political leaders to exchange ideas and learn from scholars—and leaders in business and community—about ways to kickstart an economic revival. No doubt there would be interest in the structural ideas that rely on federal action; but in addition, people may be able to consider practical approaches often overlooked.

For example, how can individuals and communities make better use of cooperative strategies? Is there merit in encouraging migration to targeted states in the South to accrue political and economic influence?

How can people gain training and skilled jobs under the $1.2 trillion federal infrastructure program when the construction industry)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2022/the-construction-industry-labor-force-2003-to-2020/home.htm__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUBuCFKC0$">construction industry has historically excluded them? Can demands for reparations be coordinated in ways that build institutional wealth like development banks?

Which youth programs work best in helping young men estranged from the labor market to recover? And how can workforce development prepare middle class workers for the challenges of automation?

In closing, the CBC has a chance to restore the symbol of the 1963 March on Washington Movement. Leaders can use the upcoming march as a springboard to the September conference and issue the call there. In these trying times, it is incumbent upon the national Black political class to weigh the merits of a unity summit.

Roger House)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://emerson.edu/faculty-staff-directory/roger-house__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUkIY4RV0$">Roger House is associate professor of American Studies at Emerson College and the author of Blue Smoke)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.amazon.com/Blue-Smoke-Recorded-Paperback-Original/dp/0807137200__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NU5MmVQmE$">Blue Smoke: The Recorded Journey of Big Bill Broonzy and South End Shout)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/128627332-south-end-shout__;!!LsXw!QONmanSAMXFl22UpYAuxVpPpkftFPzVmfqBUGWT7P_GtM-EVzaM_fErYmPN9xzvpVmXwEbUgsP-wfaLEZ3NUIM7LWUo$">South End Shout: Boston’s Forgotten Music Scene in the Jazz Age.