Only the U.S. military could set out to quickly build a lot of inexpensive weapons and, instead, slowly build only a handful of very expensive ones.

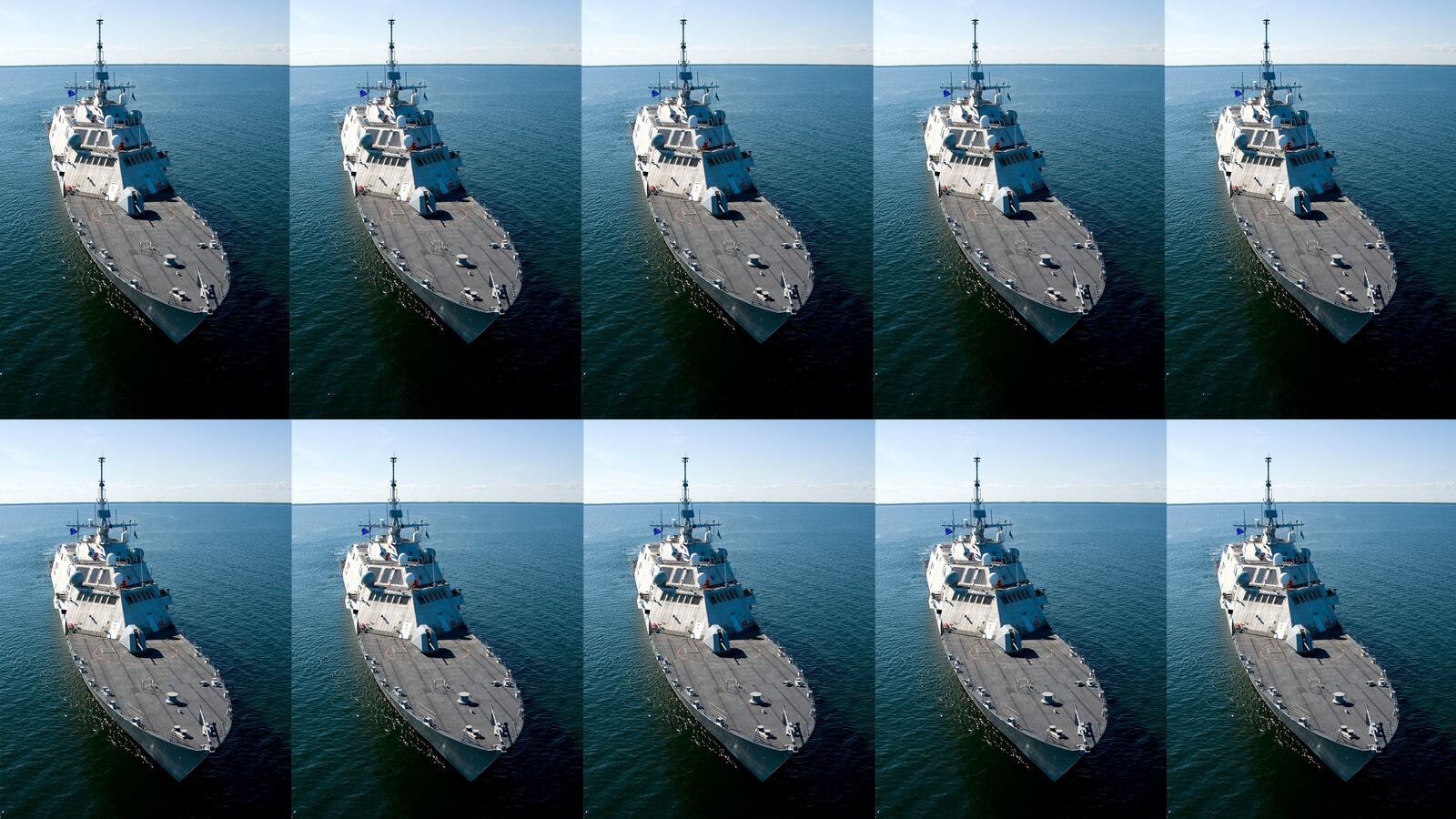

Case in point: the Littoral Combat Ship, the U.S. Navy’s latest financial boondoggle. The LCS was supposed to help save the Navy. Instead, it threatened to sink it.

Over the last 15 years the sailing branch has spent $30 billion on LCSs. In 2019 all it has to show for all that time and money is 10 combat-ready ships, only four of which the Navy actually intends to deploy over the next year, according to a May 2019 report from the Congressional Research Service.

Two of those deployments will be to the Caribbean, where the much-ballyhooed vessels will sail in big, slow circles, their crews hoping to intercept South American drug smugglers. A mere two LCSs will head to the Western Pacific, where the Navy is trying to contain an increasingly powerful Chinese fleet.

In other words, just two LCSs are doing anything even remotely useful for U.S. security. The pace of deployments could increase in coming years, but to a great extent the damage to America’s naval readiness has already been done.

The Navy and its contractors did not immediately respond to requests to comment for this story.

This isn’t how LCS was supposed to work out. In 2004 the administration of President George W. Bush insisted the Navy needed 375 warships to keep the peace and win wars. But in 2004 it had around 300 ships. The fleet had to get bigger, and fast.

The Navy believed the LCS was just the thing it needed to grow. The LCS was a new kind of combat vessel that promised to be cheap, flexible and customizable for patrols in shallow, crowded Middle East waters, among other missions.

In March 2004, the Navy bet big on the Littoral Combat Ship, tapping not one but two shipyards—one belonging to Lockheed Martin and another to Australian firm Austal—to begin building as many as four of the new warships ever year. “We need this ship today,” said Adm. Vern Clark, then the sailing branch’s top officer.

Back then, the Navy anticipated that by 2019 it would have bought 49 LCSs on its way to a total force of 56 of the versatile vessels, all at a cost of less than $30 billion, according to a 2003 report from the Congressional Budget Office. The way Navy planners imagined it, the first LCS would deploy as early as 2010.

By 2025 the shallow-water vessels would be the backbone of the Navy, the thinking went. “I predict when it is all said and done that they will be the workhorses of the fleet,” Adm. Gary Roughead, one of Clark’s successors, said in 2009.

Then the problems started. The first LCS, USS Freedom, was $400 million over its original cost estimate when it launched in 2006. To make matters worse, mechanical and structural problems festered inside the ship, the symptoms of a rushed design process. In 2010 and 2011, Freedom and a sister vessel both suffered serious maintenance failures within months of each other, sidelining the ships for months.

Freedom finally deployed in 2013 for a brief visit to Singapore. Two more LCSs sailed to Singapore over the next couple of years. Then in 2016 Freedom suffered an engine failure during a war game with the U.S. Pacific Fleet. It took two years to repair the damage. In the meantime the Navy canceled all major LCS deployments.

Not that it mattered. Even when the LCSs could sail, they couldn’t fight.

Weirdly, that was by design. To make the LCS more flexible, the Navy planned to develop plug-and-play “modules” with different combinations of weapons and robots. One module would transform an LCS into a minehunter. Another would allow it to hunt submarines. A third was for fighting small speedboats like a terror group might deploy.

But the modules suffered technical problems that, if anything, were more serious than the problems the ships themselves suffered. The “seaframes,” as the Navy euphemistically called the ships, were ready years before the modules were. The Navy has consistently had more LCSs than it has had major weapons for the LCSs.

Arguably the LCS's biggest problem was conceptual. The Navy began spending billions of dollars a year building LCSs without actually figuring out how to use them. “Apart from the Navy’s inability to properly forecast how fast these ships could be built, fielded and paid for, there is a similar tone-deafness to how they will be employed,” naval expert and author Christopher Cavas wrote.

Where previous warships were built tough in order to absorb damage, the LCS was lightly-constructed in order to save money and also to ensure that the ship rode high in the water, thus allowing it to sail closer to shore than other warships could.

But enemy defenses tend to get more dangerous the closer a ship is to land. The Navy had in effect designed a coastal warship that couldn’t risk going near the coast. “LCS is not expected to be survivable in a hostile combat environment,” the Pentagon’s Director of Operational Test and Evaluation warned in a 2011 report.

The Navy also insisted that the nearly 400-feet-long LCS be capable of reaching a top speed of more than 40 knots, around 10 knots faster than most warships are capable of traveling. But the speed requirement forced the contractors to install big, powerful engines that consumed fuel at a higher rate compared to other ships’ engines.

The LCS’s fuel-inefficiency limits how long it can spend at sea and also makes it expensive to operate, all while its initial purpose was meant to be helping the Navy expand without a major increase in overall funding.

At the end of the day, the LCS’s higher operating cost risked wiping out any savings that resulted from its cheaper purchase price. One study by defense contractor Northrop Grumman described the LCS as being only “seemingly less expensive” than other ship types.

In another effort to reduce the LCS’s cost, the Navy originally shrank its crew. Both an LCS and a typical naval frigate displace around 3,000 tons of water, meaning they’re roughly the same size. But a frigate usually sails with around 200 people aboard. An LCS initially sailed with just 75 or so, meaning some crew members had to take on twice as much work as on a standard frigate.

Crew exhaustion became a serious problem even before the LCSs began undertaking serious deployments. “The manpower planning was wildly unrealistic,” Mandy Smithberger and Pierre Sprey wrote in an investigation of the LCS for the Washington, D.C. Project on Government Oversight.

Over the course of 2015 and 2016 the Navy finally conceded it had screwed up, big time. “When I took a step back… I saw complexity, I saw instability,” Vice Adm. Tom Rowden, who at the time oversaw the Navy’s surface warships, told Bloomberg. LCS captains were “pulled in 15 different directions,” Rowden admitted.

The Navy decided to boost LCS crews to around 100 people. It more or less abandoned the concept of modules and instead began permanently installing weapons and other equipment. It started adding more powerful missiles in order to give the LCSs a fighting chance against Chinese and Russian warships.

Most damningly for its one-time vision of the fleet’s future, the Navy cut the planned production run of LCSs down to just 35 ships.

The Navy ordered its last LCS as part of the 2019 defense budget. Eighteen of the ships are still under construction. Once all 35 are in commission in the early 2020s, just 24 will be assigned to front-line squadrons. The rest will be full-time training ships or test vessels.

How many of the 24 front-line LCSs will actually deploy, and to where, depends on how successful the Navy is in its efforts to reorganize the ships, boost their crews and add heavier weapons.

Even if all 24 prove capable of deploying and actually fighting a major war at sea, they’ll represent a huge failure of the Navy’s original concept. There was a time when Navy leaders imagined sending dozens of inexpensive LCSs into harm’s way as part of a much bigger and more flexible fleet.

But the concept was fantasy. Ships are expensive for a reason. They have big crews for a reason. They take years to develop and build for a reason. They avoid enemy coasts for a reason.

Years late, massively over budget, and riddled with crippling design flaws, the shallow-water warship has turned into a financial black hole that has consumed tens of billions of dollars while producing only a handful of warships that are capable of even leaving port— to say nothing of winning a high-tech battle at sea.

LCS was supposed to help the Navy expand. In 2004, before LCS, the U.S. fleet had around 300 ships. In 2019, after LCS, it has… around 300 ships.