During the 1950s, the U.S. was trying to gain access to Mexico’s oil and natural gas reserves. Realizing that their counterpart desperately needed their technology, industrial know-how and investment capital, the U.S. opened the negotiation with a very low offer. That offer was considered so insulting that the Mexican government started to burn off its oil and natural gas rather than provide the U.S. access to its fields.

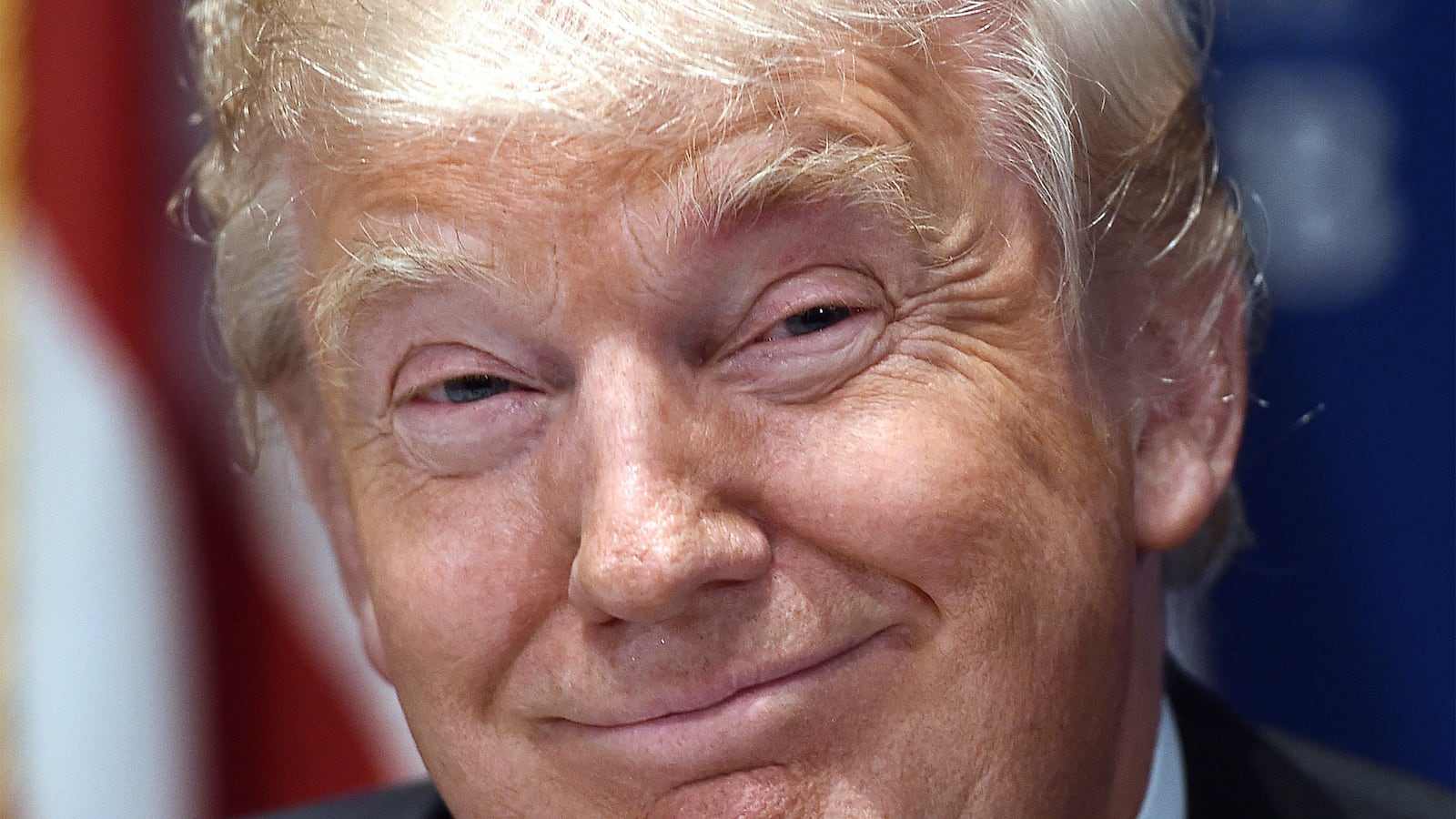

This should serve as a cautionary tale for anyone who thinks Donald Trump can improve America’s standing in the world through ultra-aggressive negotiating techniques.

In his campaign to win the Republican nomination, Trump has repeatedly touted his business acumen and negotiation skills as qualities that make him uniquely suited to be the next president.

“Right now,” Trump explained to Breitbart News, “we have the wrong group of negotiators who have led us to being totally out-negotiated.”

Trump’s preferred negotiation style—at least as a rhetorical trope—is one of power, toughness, and dominance. For him, an effective negotiator is someone adept at hardball tactics, forceful arguments, ultimatums, walkouts, threats, public blustering, and table pounding.

This rhetoric assumes that negotiations are inherently a zero-sum game. And, while such an adversarial and power-based approach makes sense within a Machiavellian worldview, it goes against decades of research into the art and science of negotiation.

On Iran, for example, Trump said on numerous occasions that he would make his positions known and walk away from the deal if his counterpart did not comply. If that approach failed, he would double up on sanctions until the Iranians returned and submitted to his demands. He would conclude the Iran deal, he boasted, within a week.

A President Trump, he likewise insists, would somehow compel the Mexican government to finance a wall along the U.S.-Mexican border.

Yet research shows that a solely competitive approach to negotiation—Trump’s preferred style—often leads to stalemates, less than optimal or satisfying solutions, damaged relationships, low levels of trust, feelings of resentment, desire for vengeance, and sometimes even violence.

In contrast, a cooperative approach to negotiation—one that perceives the conflict as a shared problem to be solved—often leads to more creative and mutually satisfying outcomes, preserved or improved relationships, higher levels of trust, and increased self-esteem.

According to Joshua N. Weiss, a negotiation expert and co-founder of the Global Negotiation Initiative at Harvard University, in recent years there has been "a very noticeable shift from a strictly competitive hardball approach to negotiation to a much more collaborative one. This is because companies understand if they burn bridges when they negotiate they lose customers in the process. More importantly, their reputation suffers dramatically. As a result, other companies hesitate, or worse, refuse to work with them.”

Indeed, studies do support the assertion that selfishness tends to backfire in negotiation. In one particular experiment one group of negotiators was assigned very greedy goals, while another group was given more moderate ones. In some instances, the greedy negotiators got more than the moderate ones, however, not without incurring significant costs: their negotiation partners ended up resenting them.

Not surprisingly, when the greedy negotiators' counterparts were presented with another opportunity to negotiate, they acted defensively, drove hard bargains, exacted revenge, and in some instances failed to reach a deal.

In another study, with over 200 negotiators, half of which were experts and half inexperienced, researchers told some of the novices that their counterparts were avaricious sharks. This was untrue. But reputation was of consequence. Those labeled sharks did badly in the negotiation: talks deteriorated, and outcomes, when they were reached, often failed to satisfy.

Trump speaks as if he is perpetually haggling in a mythical bazaar. Yet in the complex and interdependent world of international relations, thinking long-term and cultivating relationships matter.

“As a negotiator, Trump is more about achieving his short-term interests without regard for the other party or any inclination that he wants a long-term relationship,” explains Beth Fisher-Yoshida, director of the Negotiation and Conflict Resolution program at Columbia University.

“If a party loses badly and publicly,” she continues, “there is a sense of shame or embarrassment that will not bode well for the future. The other party suffered humiliation and depending on the party’s cultural orientation, will do something to right the offense. The next round will be even more challenging because it will not only be about the subject being negotiated, but also personal revenge and retaliation.”

People—no matter what station they hold in life—care about being treated with fairness and respect. They want to be heard, acknowledged, and have their identity protected. When this does not happen, when people feel they are being disrespected, ignored or mistreated they can behave in ways that make little rational or economic sense.

It’s very possible that there is a gap between how Trump talks and how he (or those whom he employs) behaves around the proverbial negotiation table. After all, even in his own book on the Art of the Deal, Trump advertises the virtues of being cooperative, accountable and positive.

However, his negotiation rhetoric leaves a lot to be desired and is dangerously perpetuating myths that social science and common sense have long buried.