It was a January evening in Venice in 1505. One can imagine the scene: well-to-do Venetians sitting around their formal tables waiting for dinner to be served while the gondoliers still on duty bundled up against the winter winds and piloted their boats down the Grand Canal.

On the eastern shore, just before they passed under the Rialto Bridge, they would glide by the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, where German merchants were housed with the wares they had brought to sell and trade in the booming port city.

What the passing gondoliers and the merchants inside didn’t yet know that evening was that a fire was breaking out in the attic of the building the Germans were assigned—and largely confined—to while they were in town conducting their business.

The fire spread quickly before it was finally discovered. Panic surely ensued inside the Fondaco as efforts were made to put out the flames and save lives and goods. But the effort was for not.

The fire raged on for another day and night, consuming the building and several lives before it finally puttered to an end.

But life—and commerce—must carry on, and quickly! Venice was proud of its place as the key trading post where goods were moved from the East to the West, and the German merchants played a pivotal role in this economic activity.

Only two days after the fire was extinguished, the Signoria de Venice, the governing body of the republic, ordered the building to be rebuilt posthaste.

And it was. But this time, the Fondaco would get a special treat: frescoes by the young artists Titian and Giorgione would cover the entire facade of the building, a spot of beauty that could be enjoyed by the the entire city…for several years, at least.

After only a few decades, the salty, wet air of Venice began to erode the frescoes, leaving only fragments of the series of masterpieces that once existed.

After the fire, when the Fondaco was rebuilt at the city’s expense, it was made bigger and grander than its previous incarnation. It was erected on the same spot, but this time, it was constructed in a square around a central courtyard.

Shops for the German merchants filled the ground floor, while the top floors contained their living quarters. The building was built “with greater magnificence, adornment, and beauty,” according to 16th-century art historian Giorgio Vasari in The Lives of the Artists.

Despite the care put into creating the new Fondaco, it still served something of a complicated role in Venetian society. It was an important space of commerce in the city, and one can imagine the respite it offered to weary Germans after weeks of traveling through difficult and sometimes hostile terrain.

But it was also a space that forced the separation and confinement of the foreign visitors. The Venetians were eager to keep a close eye on their guests in what was an attitude driven partly by xenophobia, partly by good business sense.

By requiring that the Germans set up shop in the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, the Venetians could make sure that they were examining everything that was brought in and out of the country…and then levy taxes on it accordingly.

So, while it was important that the space get back to business as quickly as possible, and while the Venetians wanted to make it a credit to their grand city, the new Fondaco didn’t need to be the creme of the architectural crop. It shouldn’t overshadow the buildings reserved for actual Venetian citizens.

And that’s where Titian and Giorgione and their possibly ill-advised frescoes came in.

At the turn of the 16th century, the artists were two of the best students in the workshop of the biggest art master in Venice — Giovanni Bellini. At 30, Giorgione was well regarded and a bit more established than his younger compatriot, 20-year-old Titian. But for both artists, the commission to fresco the outside of the Fondaco was a chance for them to prove themselves on a very visible canvas.

Frescoes were common in Venice at the time, particularly among artists who could use this public art form as something of an advertisement, even though residents of the city were well aware of the damage the hot and humid winds coming from the south could wreak on them.

“For my part, I know nothing that injures works in fresco more than the sirocco, and particularly near the sea, where it always brings a salt moisture with it,” Vasari wrote.

But this didn’t really concern the Venetian government.

In The Art of Renaissance Florence, Norbert Huse and Wolfgang Wolters point out that the government “set tight limits to the ostentation allowed to the Germans, specifying that the steps of the trading house should not extend to the Grand Canal and that ‘no marble fixtures should be attached to the Fondaco, or any stone openwork.’ Instead of the forbidden marble incrustation the Germans were allowed only frescoes, and everyone knew that they would not stand up to the Venetian climate for long.”

In 1508, the building was completed, and, shortly after, so too were the painted frescoes that adorned the entire exterior of the building. Gondoliers who now sailed pass the Fondaco would be treated to the sight of an impressive work of art that filled the entire facade along the Grand Canal.

“When completed, the Fondaco was a wonder of Venice, and the frescoes the talk of the city. They covered the facade, wrapping around the windows, integrating the architectural elements and including some painted trompe-l’oeil. They solidified Giorgione’s reputation, and helped to launch the career of Titian,” Noah Charney writes in The Museum of Lost Art.

While we know that locals were impressed by the finished piece, scholars continue to argue about what exactly Titian and Giorgione painted.

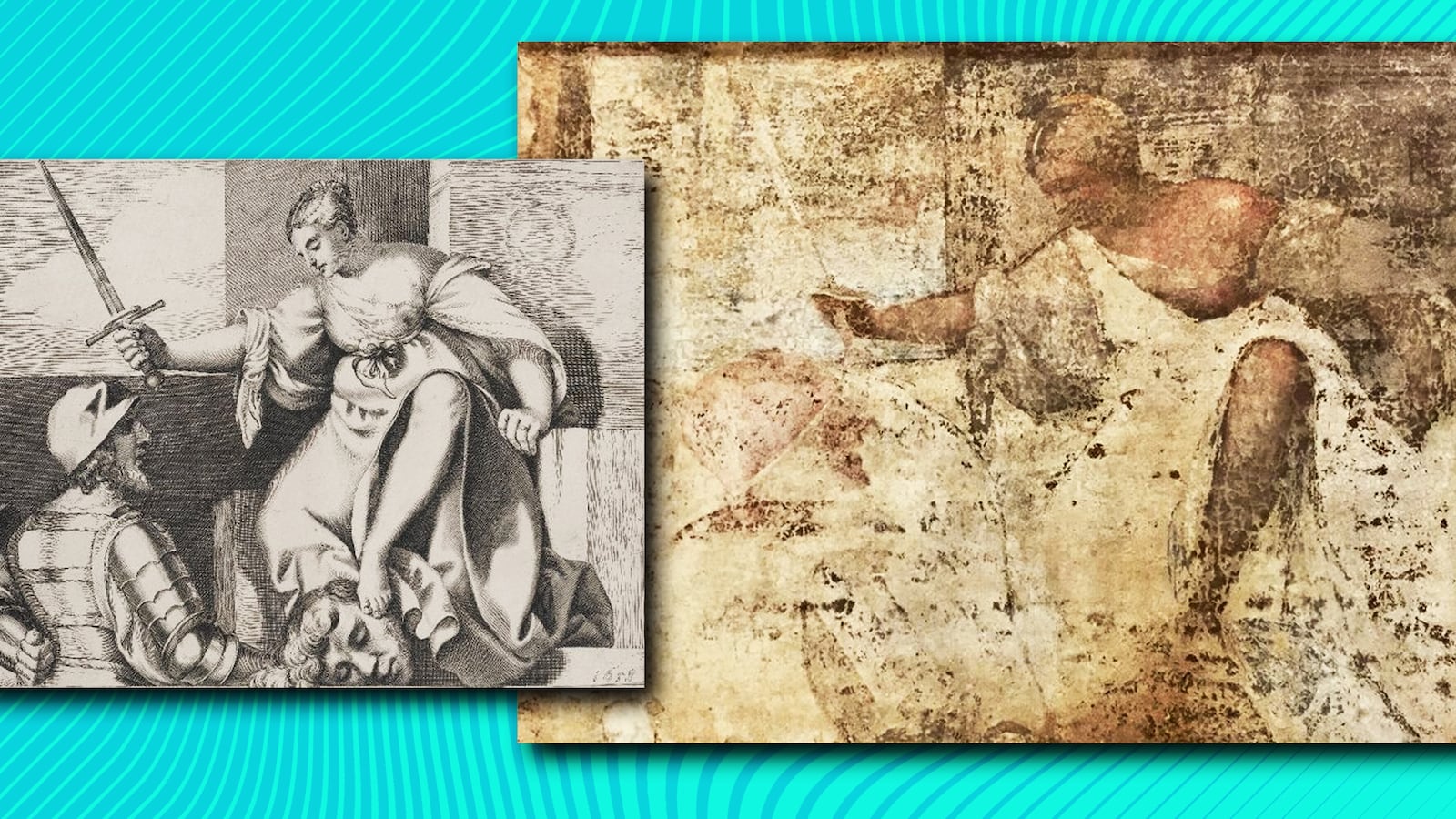

Within only a few decades, the sirocco winds had started eroding large chunks of the frescoes, and so “their influence and memory was fleeting,” Charney says. What is left of the figures and the scenes depicted is hard to piece together.

“The frescoes themselves are too fragmentary, derivative works (such as prints made after the frescoes) are incomplete or of suspect accuracy, and the textual references (such as those by Vasari) must be taken with a grain of salt as we do not know how complete or accurate they are, or if Vasari actually saw the paintings in person,” Charney writes.

But as the frescoes were washed away in the wind, their influence lingered, particularly for Titian.

The success of the commission elevated the status of the two artists and may have resulted in Titian and Giorgione facing off in an artistic battle to succeed Bellini as the leading artist in Venice, if it weren’t for a tragedy that struck two years after the work were completed.

Throughout its early history, Venice was beset by plagues that would rip through the city taking large swaths of the population with it.

In a project about the world economy, in collaboration with the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Professor Angus Maddison wrote that, while people poured into Venice during the Medieval and Renaissance periods as it became a booming economic and political empire, it also experienced “three demographic catastrophes.

"In 1347–48, nearly 40 percent of the population died when a galley brought the plague from the Black Sea port of Caffa. Two other attacks occurred in 1575–77 and 1630; each killing about a third of the population of the city.”

In 1510, before the second of these major attacks, the plague seems to have already been making its mark on the city. In that year, Giorgione is thought to have caught the disease after visiting the house of a love interest. He succumbed to the plague in October.

It was a tragedy, cutting short the life of one of the most promising artists in Venice. But it also cleared the way for Titian to become the reigning artist of Venice.

The Fondaco commission had given Titian’s career a major boost. After his teacher Bellini died in 1516, he quickly becoming the reigning artist in Venice, not to mention one of the greatest masters of the Italian Renaissance.

As the 16th-century Italian art theorist Giovanni Lomazzo put it, Titian was “the sun amidst small stars not only among the Italians but all the painters of the world.”

But very little was left of the work that helped him rise to prominence. In the 1960s, the remaining fragments of the Fondaco frescoes were moved into a Venetian gallery. In 2016, the Fondaco itself fared much better when it underwent a major restoration.

Hundreds of years ago, German traders traveled thousands of miles to trade their goods for Venetian glass, decorative arts, silks, and maritime supplies. Today, the newly restored building is once again filled with merchants, their names Gucci, Burberry, and Bottega Veneta.