Last year, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement deported 226,119 people. Jakiw Palij wasn’t one of them.

During the first three months of ICE’s 2018 fiscal year, the agency deported 56,710 people, 46 percent of whom had not been convicted of a crime. This year, ICE expects to deport 209,000 people (PDF). It is highly unlikely that Palij will be among them—even though Palij is a war criminal, the last Nazi war criminal living in the United States.

Palij served as a guard during World War II at the Trawniki forced labor camp, which also trained those participating in “Operation Reinhard,” a plan to exterminate every Jew in German-occupied Poland. He entered the country in 1949 without divulging his past and was later awarded citizenship, of which he was stripped by a federal judge in 2004 and ordered deported.

“During a single nightmarish day in November 1943, all of the more than 6,000 prisoners of the Nazi camp that Jakiw Palij had guarded were systematically butchered,” Eli Rosenbaum, head of the Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations (OSI), said after the ruling. “By helping to prevent the escape of these prisoners, Palij played an indispensable role in ensuring that they met their tragic fate at the hands of the Nazis.”

But Palij, now 94, remains a free man because no one else wants him, either. As Rosenbaum told The Daily Beast in an email, “Unfortunately, the governments of Germany, Ukraine and Poland have declined to admit Palij and no other nation has agreed to accept him.”

Palij lives quietly in Jackson Heights, Queens, on a leafy, tree-lined street less than 2 miles from Citi Field.

“Who is this?” Palij grumbled in his still-thick accent when contacted by phone. Asked about the status of his case, Palij snapped, “Forget it, forget it, forget it,” and hung up. No one answered the door during a visit to his home.

Palij arrived to America in 1949, falsely claiming on his immigration forms to have been a farmer, not a guard at a concentration camp. Jonathan Drimmer, a former federal prosecutor who worked under Rosenbaum at OSI, was the one who first tracked Palij down.

When Drimmer first went to interview Palij at his home in 2001, it felt like he had somehow been expecting him. Old Nazis who settled in New York City “were waiting for that knock on their door for a long time; they knew that one day someone was going to show up asking questions,” Drimmer told The Daily Beast.

“It was like puncturing a balloon,” Drimmer recalled. “When I said, ‘I’m Jonathan Drimmer from the Department of Justice, I’m here to talk to you about your wartime service,’ you could see all the air just go out of him.”

Guards at Trawniki were used by authorities to clear out ghettos in German-occupied Poland, including Warsaw, Częstochowa, Lublin, Lvov, Radom, Kraków, and Białystok. The Trawniki forces were also used as escorts for trains carrying Jews from ghetto to death camp.

Drimmer had obtained a copy of a wartime statement placing Palij at the Warsaw Ghetto Liquidation in the spring of 1943. Palij, unsurprisingly, denied being there. If he wasn’t in Warsaw, Drimmer asked Palij, then where was he? Palij then placed himself himself at Trawniki to avoid implicating himself in connection with atrocities committed in Warsaw.

Palij signed an affidavit confirming his Nazi service before Drimmer left the house. Denaturalization and deportation proceedings began shortly thereafter.

Though Palij lost his citizenship, his attorney, Ivar Berzins, knew the complex issues surrounding Palij’s deportation would be tricky and used it to his client’s advantage.

“His whole strategy was, ‘I don’t think you’re going to be able to get this guy out of the country, so we’re not going to waste our time and waste his money putting a spirited factual defense together,’” Drimmer said. (Berzins declined to be interviewed for this article.)

OSI, which was renamed the Human Rights and Special Prosecutions Section in 2010, employed a team of full-time historians who specialized in Nazi Germany and had access to archives of captured wartime documents throughout Europe and the United States. They combed through these files looking for the names of people who served in units responsible for war crimes, then compared those names against American immigration records looking for a match.

It was painstaking work made oddly easier by the Germans’ penchant for precise and systematic record-keeping, said Stephen Paskey, who was a senior trial attorney at OSI with Rosenbaum and Drimmer and led the government’s case against another former Nazi guard, John Demjanjuk.

“If a group of guards was transferred from one concentration camp to another, an inventory clerk would record every item each one left with, down to the number of socks and underwear, and then the inventory clerk at the camp they went to would sign them in, down to the number of socks and underwear they had with them,” Paskey told The Daily Beast.

“The problem [building cases against] modern human rights violators is that there are lots of people from places like Rwanda and Somalia that have blood on their hands but there’s no way to prove it. In the WWII cases, we didn’t have to rely on eyewitnesses,” Paskey added.

Nazi war criminals can’t be prosecuted in the U.S. under the War Crimes Act because their crimes were committed overseas, the people who committed them were not U.S. citizens at the time, and the victims weren’t U.S. citizens, explained Paskey. Instead, they are tried for lying about their Nazi service on their American immigration and citizenship applications.

Germany has prosecuted a handful of them, including Demjanjuk in 2009. Recently, the German constitutional court ordered 96-year-old Oskar Groening, the so-called Bookkeeper of Auschwitz, to serve four years in prison for his wartime activities. Groening died on March 9, before he could begin his sentence. Germany has also indicted 11 former death camp guards who are scheduled to face prosecution in 2018. But Efraim Zuroff, a former OSI researcher and current director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Jerusalem, told The Daily Beast that a change to the country’s prosecution policy all but ensures Palij won’t face charges there.

“They’ve done a pretty good job the last few years in pursuing individuals for Nazi atrocities who were found in Germany,” said Drimmer. “What they have not done a good job of is taking guys like Jakiw Palij, who were found outside of Germany, but are every bit as culpable, if not more culpable, than the individuals found inside Germany’s borders.”

Every November, on the anniversary of Kristallnacht, New York State Assemblyman Dov Hikind leads a rally outside Palij’s house.

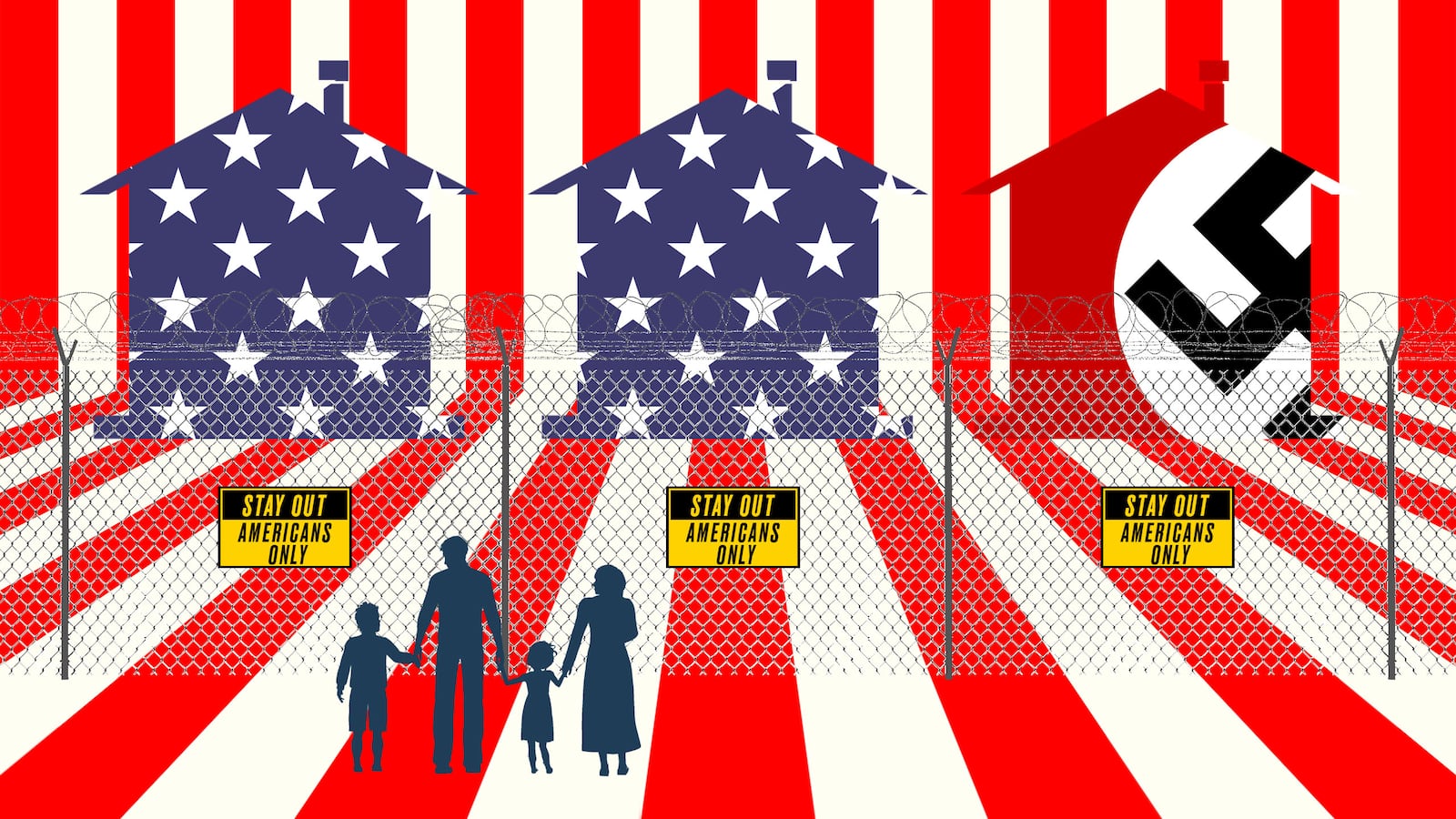

“You know, we’re throwing people out of this country who have been living here for 20 years and have families, and here we have a Nazi living in Queens,” Hikind told The Daily Beast. “How can that be? How is this possible?”

Hikind, whose parents both personally survived Holocaust concentration camps, has called on Attorney General Jeff Sessions to take Palij into custody as an illegal alien and hold him in detention while his deportation case continues to wind its way through the system. Hikind says he has been “pushing every button imaginable, there have been many attempts over the past six months to make something happen—we even got in touch with the son-in-law [Jared Kushner].”

Last October, the State Department told Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) in a letter that the governments of Germany, Poland, and Ukraine had rebuffed their overtures in negotiating Palij’s return. However, the letter said officials remained “hopeful that ongoing engagement with our allies will eventually result in Mr. Palij’s long overdue removal.” In November, Assistant Attorney General Stephen Boyd wrote to Hikind, “The Department agrees fully that Palij should not live out his last days in this country.”

It will continue to be an uphill battle. According to ICE statistics, 8,275 people with deportation orders remained in the U.S. between 2012 and 2015 because no other country would take them (PDF); the agency says it “does not have the authority to force removals upon a sovereign nation” (PDF). An ICE spokesperson said nine countries are currently classified as “uncooperative”: Burma; Eritrea; Cambodia; Hong Kong; China; Laos; Cuba; Iran; and Vietnam. Germany, Ukraine, and Poland are not on the list.

ICE declined to comment and said to speak to the State Department, which also declined to comment. A U.S. government source who is close to the situation and requested anonymity to speak freely said of Palij, “ICE cannot remove him unless he has travel documents and Germany would have to provide those to the U.S. government to remove him and that has not happened. This has been over a decade now since he was ordered removed, but we haven’t gotten Germany to comply. Here is someone who wore a German uniform and represented Germany in WWII, and the German government hasn’t made any effort to ensure he is back there.”

However, said Stephen Paskey, “The real issue is whether it’s a priority for anyone at the State Department, and generally I don’t think it has been. I don’t know for certain what they’ve done, but I think the results speak for themselves.”

And so, Palij will almost certainly live out his last days on U.S. soil. It’s happened before. Take the case of retired auto worker and accused Nazi war criminal John Kalymon. In the late 1990s, investigators accused Kalymon of having served in an SS-allied Ukrainian auxiliary police unit during the war; in 2007, as with Palij, a judge ordered him denaturalized and deported for hiding this fact on his decades-old immigration forms. He died seven years later, at home in Troy, Michigan. (Kalymon’s son, Alex, told The Daily Beast that admitting the truth about his Nazi service to U.S. officials would have been a death sentence for his father “at that time, under Stalin, especially because he had been employed while the Germans were in charge of the town, working for the Germans.”)

“I’m just hoping that one day I wake up and I’m pleasantly surprised that we’re finally getting rid of this individual from this country,” said Hikind. “It’s way overdue.”

To Jon Drimmer, the notion that Palij remains in the United States brings up “an interesting philosophical question.”

“We in the United States obviously care about being able to pursue people who participated in genocide as vigorously as we can, but do others feel that way?” he asked. “You have a guy like Jakiw Palij, who participated in the slaughter of thousands of people, who is stuck in the U.S. because no one else is willing to take him? Are we that deeply out of sync with the rest of the world in terms of pursuing individuals who participated in genocide?”