CHILPANCINGO, Mexico—The safe house sits on a side street in a barrio that looks out on the well-lit downtown of Guerrero’s state capital and the dark foothills beyond. A late-model pick-up truck is parked in the street, and the surrounding alleys are scrawled with graffiti. It’s just past sunset on a late summer evening and a woman is trudging up the hill with a basket of bread, calling out her wares. Otherwise the street is silent. Then the hit man steps from the shadows behind the parked truck and waves me on toward the safe house.

We sit at a bare table in the kitchen on the second floor. The tabletop is scored and oil-stained, as if machinery or heavy weapons often are served there. In one corner sits a shrine with small statues of the saints, Holy Judas among them. A hand-carved jaguar mask hangs on the walls. I notice that the hit man has seated himself at the table in such a way that he can see out both of the room’s windows at once. The curtains are open and the view looks out on the street below the safe house. A car approaching from either direction would be visible a long way off.

The hit man tells me in Spanish to call him Capache.

“Is that your real name?” I say.

“That is what you can call me,” Capache says.

The word translates as “trap” or “trapper.” That is what you can call me.

Capache was once a sicario for the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), which recently eclipsed the Sinaloa Cartel—Chapo Guzman’s old outfit—as Mexico’s largest criminal syndicate. Then, about two years ago, Capache switched sides to oppose CJNG and its allies. He currently serves with an autodefensa [self-defense] force that has taken the law into its own hands in the name of combating political corruption and organized crime.

Over the last few years, as violence has reached historic levels, autodefensas have become increasingly common in Mexico. The Oscar-nominated documentary Cartel Land depicted the rise and fall of one such group. Academics have become increasingly interested in the phenomenon.

“When a community is no longer protected by a sovereign state the contract between the government and the governed is effectively broken,” says Robert Bunker, a professor at the Strategic Studies Institute of the U.S. Army War College, in an email to The Daily Beast. “At that point local citizens who are being robbed, raped, and who are living under the constant fear of bodily injury and death have the option of either fleeing, joining the local crime groups oppressing them, or standing up and taking matters in their own hands as vigilantes.”

Capache, having undergone a rigorous and bloody training regimen as a CJNG recruit, now uses his paramilitary background, his knowledge of the dark arts of assassination, to strike back against the narcos. He works as a “cleaner” in Chilpancingo, stalking and killing cartel members who, in his words, “prey on society like vampires.”

Jeremy Kryt

An autodefensa leader I’ve interviewed in the past helped arrange a meeting with Capache, who has promised to share unique insights into the operational strategies used by two opposing sides in Mexico’s worsening Drug War.

“I feel good about the work I do,” Capache says, without taking his eyes from the outside windows. “It’s not easy, and you have to watch your back. But I’m proud of it,” he says.

“I’m defending people who can’t defend themselves. I’m fighting back. The police don’t do anything against the cartels. So if we don’t,” he asks, “who will?”

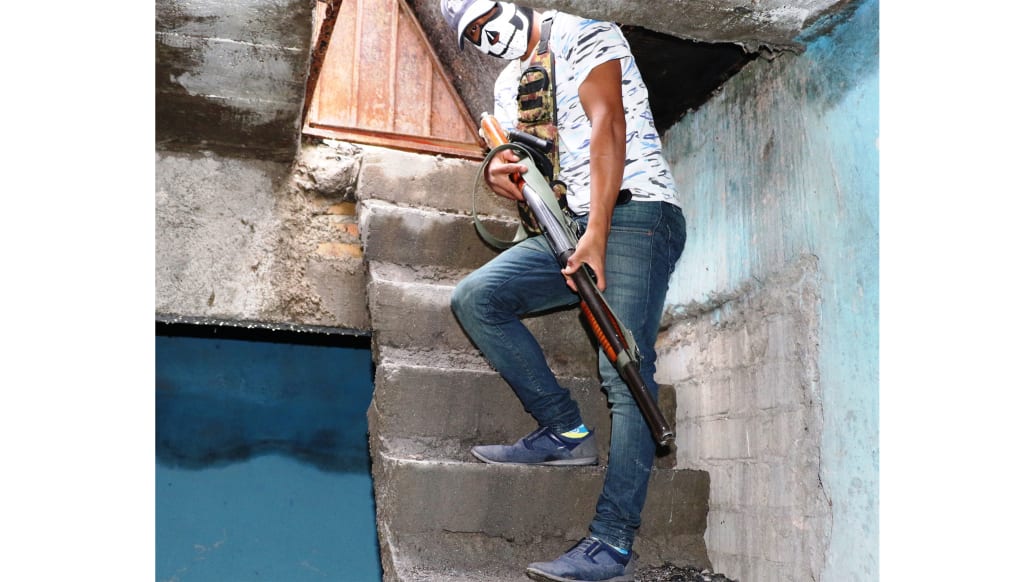

Capache looks to be in his early twenties. He wears jeans and desert-issue combat boots. A tight-fitting, long-sleeve camouflage T-shirt shows off the shoulders of a dedicated weightlifter. He’s got skull tattoos on the back of his right hand, a stud earring, and a finger ring that bears the head of a snarling wolf.

Certain sicarios I’ve met in the past have come across as arrogant, eager to boast about their exploits. Tout their love of violence for its own sake. Others are given to lamentations for their misdeeds. But Capache is different. Formal and soft-spoken, he talks of his past without braggadocio or any gnashing of teeth, but instead with an almost monotone matter-of-factness, as if the spirit of youth has been burned out of him by all he’s seen. Turned into an old soul before his time.

“I was just 14 when I left home to join the [Jalisco] Cartel,” he says. The son of a single mother with 10 other children, Capache had stopped going to school the year before because the family had no money to pay for his tuition. He was working in a restaurant in the village of Ocotito when a childhood friend recruited him to enter the CJNG’s training program.

“We had nothing. No money to eat with. I was tired of seeing my mom go hungry. And I knew I could make 10 times more working for them. As soon as I heard the offer I knew that’s what I had to do. Less than a week later I was on a bus for Jalisco.”

CJNG leader Nemesio Oseguera, aka “El Mencho,” has long sought to control drug production zones in Guerrero, which is the point of origin for about 50 percent of the heroin that enters the U.S. Lately it’s also become an important staging ground for synthetic drugs like fentanyl, which is mixed with heroin in processing labs located in the state’s remote and lawless mountains. An extensive recruitment effort aimed at the masses of impoverished young men with bleak futures from across Mexico is one of the reasons CJNG has become so powerful so fast.

Less than a decade old, the CJNG has already proved itself “to be an extremely violent, predatory, and ascendant cartel backed up by increasingly capable paramilitary forces,” says Bunker. “When pushed by the Mexican state it is also not afraid to directly strike back and ambush federal forces.”

Jeremy Kryt

Mencho’s mafia is now present in some two dozen Mexican states, as well as the U.S., South America, Europe, Asia, and Australia, according to Bunker. While many crime groups in Mexico act more like loose coalitions, with little top-down planning or organization, Mencho has taken a different tack.

As Bunker explains, part of the secret to his group’s success is “the centralization of CJNG under one leader and some capable senior officers,” which allows for the close planning and coordination needed “to shift its paramilitary units from one operational area to another.”

Capache arrived in Guachinango, state of Jalisco, with little more than the clothes on his back. He slept with other young recruits in a cluster of tents. Some of the instructors were retired members of the Mexican special forces. Others were active-duty military personnel who were also on the cartel payroll. One of the first things they told Capache was that he did not have the right to leave.

“At first I missed my family and thought about running away. But if you tried to escape you’d be hunted down and killed. I saw others try to get away and they were always caught.” Some of those would-be escapees were doused with gasoline and burned alive in front of their comrades, Capache says. Others had explosives taped to their body and ignited.

“There was no going back,” he says, seated at the scarred wooden table in the safe house.

As an initiate Capache received general infantry-style training, including small-unit tactics, target practice with assault rifles, belt-fed machine guns and grenade launchers, and field-stripping weapons while blindfolded.

Large-scale gangs like the CJNG consider this kind of curriculum worth the cost of investment because “criminal groups that field untrained gunmen get chewed to bits in [armed] engagements with cartel personnel that have better paramilitary and military levels of training,” Bunker says.

In addition to such traditional schooling, Capache says he and other recruits were also forced to undergo arduous trials meant to desensitize them to pain. One such exercise involved forcing trainees to undress beneath wasp nests lodged in trees.

“Then they [drill instructors] hit the nests with poles or rifle barrels until the wasps came out to attack us. You had to stand there for 10 minutes and without moving at all. If you moved or screamed they beat you for it,” he recalls, “so it was better just to take the pain.”

Jeremy Kryt

After about three months of training it was time for the “final exam,” which involved “cutting people up a special way,” Capache explains. Recruits took turns administering a specific, byzantine series of stabs and slashes to a live victim—usually a thief or petty criminal the cartel deemed deserving of such punishment. The first series of ordered knife cuts was meant to torture for information without killing. Then to strike fatal blows. And at last to cut up the body by hand for disposal.

And if someone didn’t want to participate in such a test?

“You knew they would kill you if you refused,” he says. “It was a way to prove you were loyal to the cartel.”

Bunker says such rituals have become commonplace in Mexico’s underworld:

“The dismembering of a victim and/or eating their flesh is a homicidal and heinous act that bonds [recruits] to the cartel as if they had joined a cult. It is viewed as a rite of passage into your new life and burns your moral and ethical bridges with traditional society.”

Capache started work for the cartel as a halcon, or spy, in the city of Ameca, Jalisco. Posted in houses near strategic points around the city, he would spend 12-hour shifts calling out the movements of police, soldiers, or rival gang members to the local command center via coded radio transmissions. During this time he also helped package and ship assorted narcotics, including cocaine, marijuana and crystal meth. Later he served as a full-fledged sicario and says he was involved in “seven or eight” firefights against opposing bands or authorities.

Because he was big for his age, had excelled in the organization’s training program, and served well in combat he soon graduated to serve in an elite, 35-man bodyguard unit. The platoon-sized force was in charge of security for one of Mencho’s regional commanders, a mysterious man known only as “090.” (According to Capache, the numerical sequence was chosen because it is also the Federal Police radio code for a homicide.)

Finally he was sent back to Guerrero to help recruit others and pave the way for CJNG’s takeover of the state. He’d been in the Chilpancingo area for only a few months before he was captured by an autodefensa force called the United Front of Community Police of Guerrero State (FUPCEG). One of the largest groups of its kind in the country, FUPCEG boasts a fighting force of almost 12,000 men stationed in more than 30 municipalities. After a half-year of “re-education classes,” as Capache calls them, he was invited to join FUPCEG’s anti-cartel strike force.

Cartel foot soldiers joining policia comunitarios, or community police, as autodefensas are often called in Guerrero, is a relatively common occurrence. Although their expertise is valued by the self-defense forces, their presence can also contribute to a blurring of the line that separates vigilantes from the organized crime groups they seek to oppose.

Jeremy Kryt

At first Capache helped train the vigilantes’ fresh members, passing on what he’d learned in Jalisco about tactical maneuvers and weapons training. He also took part in open battles in the mountains against a regional mafia said to be allied with CJNG, called the Cartel del Sur. Eventually he was sent to back to Chilpancingo, as part of several elite squads assigned to FUPCEG’s clandestine limpieza [cleansing] program.

The autodefensa leaders held a press conference last March, boldly announcing that they would start targeting criminals in the city. The expansion of their operations came after a months-long campaign to liberate small towns and villages in the surrounding sierra from the Cartel del Sur, which is led by a particularly ruthless capo named Isaac Navarette Celis.

“The Cartel del Sur wants to intimidate the population. They want to dominate Chilpo and control everything. They rob and extort, they kidnap and murder. If they see a woman they like on the street, they just take her. Their ambition leads them to do things they shouldn’t,” says Capache. “That’s why we’re here to clean up.”

Part of that cleaning-up process involves identifying members of the cartel for capture or assassination. When the order goes to out for a hit in Chilpancingo, Capache receives a message with directions on his cell phone. Shortly thereafter a man arrives at the safe house with an untraceable firearm, usually a semi-automatic pistol. (“I like a 9 mm Beretta when I can get one,” he says, “because they almost never jam.”)

Capache works as part of a three-man crew that includes a driver and a scout, and they take turns acting as the designated shooter. The safest method, he says, is to engage the intended target from the back of a motorcycle or car.

Jeremy Kryt

It gets more difficult when the mark is with a group or protected by bodyguards. In that case, “we have women who help us to get them alone,” he says. Once the target is vulnerable the women find an excuse to step away and make a phone call.

“They tell us where they are and what he’s wearing and after that it’s easy,” says Capache. In case the targets are armed, he shoots them first in the head, then in the chest, instead of the other way around.

Local news reports indicate a string of unsolved killings of young men in and around the provincial capital in the wake of FUPCEG putting Navarette Celis’s gang on notice this spring. Capache is reluctant to provide the names of his victims, and my sense is that he fears blowback from both his superiors in FUPCEG and law enforcement if he reveals traceable information. However, the independent press coverage from the last several months shows multiple public assassinations in the barrios and urban zones where autodefensa cells like Capache’s are said to operate. Those reports also jibe with specific details of their preferred M.O., such as dismemberment and conducting hits by motorbike.

Capache claims five confirmed kills as part of the FUPCEG hit squad, but says that total doesn’t count his work for CJNG or pitched battles with the autodefensas. Such combat experiences are messy, he says, and “not like on TV.”

It’s hard to know if those he shot in firefights actually died or were only wounded, he says, and he doesn’t want to overestimate a kill count that might be incorrect simply to look tough. In answer to a question about what he feels in battle, or during the act of killing an unsuspecting target, he says:

“No siento nada mas que adrenalina.” I feel nothing but adrenaline.

When I ask if he likes the adrenaline he confesses he does but says it’s also “depressing when your friends get hurt or killed.”

He glances away from the open windows to look me straight in the eyes.

“But your friends’ pain also helps you keep fighting,” he says, “because it makes you hunger for revenge.”

Critics point out that FUPCEG’s undercover ops differ little, if at all, from the tactics employed by the cartels themselves.

“They call themselves community police, but they’re really no different from sicarios,” says Manuel Olivares, director of a Chilpancingo-based NGO called the José María Morelos y Pavón Regional Center for Human Rights. The NGO director also charges that the state government is complicit in allowing FUPCEG to operate outside the rule of law.

“Ultimately they’re enabled by the politicians,” he says. “The criminals could never carry out a campaign of terror without their support and permission. The level of corruption [in Guerrero] is just incredible. We have a government that cares only for itself.”

Bunker agrees with Olivares about “the authorities turning a blind eye to vigilante justice” in Chilpancingo.

“If the autodefensas want to engage in extrajudicial killings by means of death squads to take cartel gunmen and their other personnel off the streets it’s a freebie for the overwhelmed authorities. Cartel del Sur has a barbaric reputation as far as torture-killings and other deprivations go, so [FUPCEG operations] remove some of the hardcore criminal element plaguing the community.”

But Bunker also warns of the danger inherent in relying on civilian militias.

“Once autodefensas form they are immediately susceptible to outside criminal influences—such as cartel penetration and manipulation—or they can become corrupted by their new found position of power and become an armed gang in their own right.”

Indeed, some local press reports have linked FUPCEG to a shadowy group called the Sierra Cartel, a long-time rival of the Cartel del Sur.

Back in the safe house overlooking Chilpancingo, Capache insists FUPCEG’s mission is not about taking over the narcotics trade.

Jeremy Kryt

“We’re here because the people have asked us for support. We came to keep the cartel from killing in this pueblo. We’re not against selling coke or other drugs, so long as they don’t hurt anybody,” he says in that same neutral and affectless voice. “All we want is peace.”

Capache now makes enough from his work for FUPCEG to help his mother and siblings. He married not long ago, and has a daughter just a couple of months old. He can’t visit his family often, he says, because he doesn’t want to put them in danger.

Near the end of our interview, I ask him if he ever considers finding another line of work.

Capache says he’d like to open his own restaurant someday, but admits it would be hard to leave the autodefensas.

“The work is dangerous, but it’s for a good cause,” he says. “I finally feel like I’m doing something right.”