MANAGUA, Nicaragua—I've seen a lot of hard things in this country since first coming here to cover war 40 years ago. But what I saw during a recent four-day visit was just as unsettling.

During the Sandinista “final offensive” that toppled the Somoza dictatorship in 1979, I photographed charred corpses set on fire to reduce the spread of disease and then torn apart by animals scavenging for food. I watched National Guardsmen pile like cord wood the ravaged bodies of Sandinista rebels. I made pictures of Red Cross workers inspecting bodies of men tortured and killed.

During the 1980s Contra War, a young combatant told me coldly how he and his colleagues dispatched some prisoners they had taken while fighting in the northern mountains. “They had faces like dogs,” he said, as if that explained everything. As if that were true.

I photographed families on both sides of the political divide traumatized by the death or injury of their young men sucked into a war that would benefit neither side.

They were times of great hardship but they also were times of great hope. Hope for a new beginning in a country tired of living for too long in the grip of a U.S.-backed dictatorship.

I returned to Nicaragua this month, in part, to witness the July 19 celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution, and to be clear, none of the things I saw during my trip measure up to the horrors of the 1979 insurrection or the decade-long Contra War. But what I found was the foundation for a new cycle of violence.

Discontent with their Sandinista rulers has been festering for years among many Nicaraguans fed up with the corruption, nepotism, arrogance and lies of a government led by former Sandinista guerrilla leader and now President Daniel Ortega and his wife, Vice President Rosario Murillo.

The top blew off in April 2018 when students conducting peaceful protests of government pension reforms were met with lethal force by government forces and pro-Sandinista thugs known as “turbas” who killed at least 325 people and wounded 2,000 others, according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Since the violence, some 60,000 Nicaraguans have fled the country in fear for their personal safety.

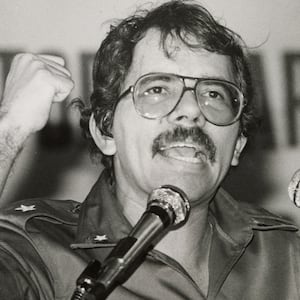

Ortega was a member of the five-person Junta of National Reconstruction that took power immediately after the overthrow of the U.S.-installed Somoza dictatorship. He was elected president in 1984 after clean, internationally supervised elections, inspiring nearly universal support and hope that his country would break the banana republic tradition that had become the rule for so many years in so many Central American countries. He was voted out in 1990 and, for the first time in Nicaragua’s history, relinquished power in a peaceful handover to a successor, in this case Violeta Chamorro.

After years of “ruling from below,” Ortega and the Sandinista party won the presidency again in 2007, and since then have cut devilish deals to perpetuate their hold on power with some of the most abhorrent sectors of Nicaraguan society. He rigged the constitution to potentially allow him to be president for life. He now controls the vast majority of news and information outlets. His policies allow the rich to get richer—this in the second poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. To win the backing of the Catholic Church, he passed legislation banning all abortion—even when the mother’s life is at risk by proceeding with a pregnancy.

I attended a rally in the main plaza of the capital city of Managua. And although the plaza and the avenues leading to it were packed with tens of thousands of Nicaraguans, I saw a different Nicaragua there—a Nicaragua seemingly void of the altruism and the idealism I saw in the early days of Sandinista rule. I saw a Nicaragua deeply divided between supporters and opponents of Sandinista rule. I felt uneasy. Too many people watching me from the corners of their eyes or behind dark glasses.

I rode through the neighborhood where Ortega and his wife live, and saw a cordon of concrete, steel, and men with guns barricading traffic to the presidential house from at least five blocks away in every direction.

I saw government paramilitaries dressed in black guarding a radio and television station raided and sacked by government forces who also jailed the station’s owner. I visited a church where government forces and their thugs killed two protesters who had taken refuge with dozens of others after being pursued by police and pro-Sandinista mobs. I saw where bullets slammed into the church, gouging deep into its concrete walls.

I watched a seasoned war correspondent fight back tears while describing the April 2018 uprising and how government forces and allies killed with abandon on the streets of the capital city of Managua.

Journalists told me they are attacked online and in the streets just for doing their job. Many have fled the country. I saw articles published in opposition newspapers openly referring to the Sandinista government as a “dictatorship,” and calling Ortega and Murillo “dictators.” I read venomous online posts by government supporters threatening critics of the Sandinista regime.

I saw the giant decorative steel trees erected across Managua on the orders of Vice President Murillo—about 150 of them all over the country. Each reportedly costs about $25,000. I heard reports that the importation of steel to make the trees, the installation of lights on each of them, and the guards needed to protect them against citizens who see them as the embodiment of poor governance and corruption, all are handled by businesses owned by Ortega’s and Murillo’s children. And about half of them have been torn down by protesters.

I visited shopping malls, restaurants, bars and hotels—now largely devoid of foreign tourists who once flocked here to bask in the tropical sun and to enjoy the warm, good-humored hospitality this country is known for.

I listened to one former Sandinista supporter voice deep concern that current government policies could spark yet another round of violence—meaning all the blood and sweat of the past 40 years was spilled for nothing. When all peaceful means of change are met with violent repression, this person said, a violent response becomes inevitable.

In conversations with Nicaraguans, I listened carefully and waited for some signal of their political leanings, wary not to offend. The Sandinistas still have support in Nicaragua. Critics argue, however, that the Sandinistas purchase that support with special privileges, material favors, or the security of a decent job.

I asked one ardent Sandinista supporter how Ortega could allow things to get so out of control.

“Ortega no controla ni verga!” this person said of the 73-year-old president (“Ortega doesn’t control a fucking thing!”) instead blaming the current state of affairs on the president’s wife, a version of events that I heard repeatedly during my trip.

As I toured this country that I have learned to love, I wondered what Augusto César Sandino, or the founders of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), would say of today’s system called “Sandinismo.” I wondered if they would think today’s version of Sandinismo is a valid reflection, or a mutation, of their original ideals.

On the morning of my departure from Nicaragua, I packed my bags and paced the hotel room. Through the hotel windows I watched the palm trees sway in the summer breeze, the sky outside a joyous, bright blue totally inconsistent with the gloom in my heart. I paced some more, trying to process all the hard things I had seen here. I sat on the edge of the bed, contemplating the specter of another national convulsion of violence.

For this trip, I had seen enough.