In These States, the Disabled Could Go to the Back of the Ventilator Line

Clemens Bilan/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

Policies in 25 states would ration care in ways disability advocates have denounced, a Center for Public Integrity analysis shows.

Before the coronavirus, Matthew Foster dressed up as the giant mouse Chuck-E-Cheese for work, hung out with his girlfriend in a Barnes & Noble coffee shop and every Wednesday went to the movies with friends.

Now he FaceTimes his girlfriend, talks to his reading coach on Zoom and helps his mother around the house.

The 37-year-old stays close to home. If he gets COVID-19, his family fears for his life.

That’s because Foster has Down syndrome, and he lives in Alabama, where people with “severe mental retardation... may be poor candidates” for a ventilator if hospitals run short during this pandemic, according to a state policy that until recently was posted on the Alabama Department of Public Health’s website.

After disability advocates complained, the state took down the policy and pointed to new, vague guidance. But Foster and his family are still apprehensive.

“I’m scared for Matthew,” his mother, Susan Ellis, said. “I was outraged and still am that any decision-maker or policy-maker in our state would think so little of people with intellectual disabilities that they would actually say an IQ score determines whether you live or die.”

Alabama isn’t the only state where people with disabilities and their loved ones have reason to worry.

The Center for Public Integrity analyzed policies and guidelines from 30 states meant to direct how hospitals should ration ventilators if they don’t have enough. All but five had provisions of the sort advocates fear will send people with disabilities to the back of the line for life-saving treatment.

These policies take into account—in ways that disability advocates say are inappropriate—patients’ expected lifespan; need for resources, such as home oxygen; or specific diagnoses, such as dementia. Some even permit hospitals to take ventilators away from patients who use them as breathing aids in everyday life and give them to other patients.

The remaining 20 states either have not established rationing policies or did not release them.

Doctors and medical ethics experts say these states need to have policies in place now, before coronavirus cases peak, and should not cloak them in secrecy.

Expecting doctors to make heart-rending decisions on who lives and who dies, experts say, runs the risk that they will lean on personal biases and stereotypes, even unwittingly.

“There is a long history of people with disabilities being devalued by the medical system. That’s why we have civil rights laws,” said disability-rights activist Ari Ne’eman. “We don’t have an exception in our country's civil rights laws for clinical judgment. We don’t take it on trust.”

Weighing Lives

Disability advocates have already filed formal complaints with the federal government about the rationing policies—sometimes called “crisis standards of care”—in Alabama, Kansas, Tennessee and Washington. In response, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on March 28 issued a bulletin reminding states that their plans should not discriminate.

Many hospitals are racing to figure out who will get life-saving breathing machines if they run out, even as they also rush to add as many intensive-care-unit beds and ventilators as possible. COVID-19 attacks the lungs; in severe cases, patients need ventilators to help them breathe.

Even conservative estimates of the looming peak of the pandemic suggest that the U.S. will need an additional 24,000 ventilators for critically ill patients in coming weeks, while more dire predictions put the number in the hundreds of thousands. Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, said Sunday his state could run out of ventilators this week.

Some hospitals will likely be worse off than others, said Dr. Thomas Tsai, a physician and researcher at the Harvard Global Health Institute.

“The reality on the ground is likely going to differ very dramatically for each individual hospital and each individual location,” he said. “There are very real pain points.”

Experts agree that, when ventilators run out, medical professionals need clear rationing guidelines that ensure all patients are treated fairly, and that a designated triage officer or committee should make the judgments.

Doctors generally are not used to weighing their patients’ lives against others and do not want to make such decisions themselves, said Dr. Jeremy Lazarus, a former president of the American Medical Association, which represents doctors.

“Having the institution make the call, in a systematic way, about who gets a ventilator and who doesn’t is far preferable,” he said.

In half of states, however, policies meant to guide hospitals are riddled with problems similar to what disability advocates have already denounced in their federal complaints. They range from discriminating against patients with certain disabilities, as the Alabama policy does, to weighing how long patients are likely to live — a practice that may also disadvantage African American men, who have shorter average lifespans.

Disability advocates say they want state policies to be based on how likely each patient is to survive the disease being treated.

“The point is, ‘Are you looking at this person as a full individual and not using a bunch of external factors or value judgments about what their life is like?’” said Shira Wakschlag, associate general counsel at The Arc, one of the disability advocacy groups that filed the federal complaints. “You have to look at the individual and not just work off stereotypes about a broad diagnosis.”

People with disabilities have long had a tortured relationship with the U.S. medical system, especially when it comes to end-of-life care. Dr. Clarissa Kripke, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, medical school, told the National Council on Disability she had witnessed doctors prematurely attempt to force people with disabilities to go to hospice.

Ivanova Smith, a disability-rights activist in Takoma, Washington, who has an intellectual disability, said her uncomfortable experiences with the medical system make her worry she would be treated unfairly if her state rationed care. A doctor once chastised her for showing up to an appointment without her husband, she said, and after the birth of her daughter, nurses spoke to her in patronizing tones and made fun of her nearsightedness. She said the Washington policy reminds her of eugenics.

“I would hope that they would try to do everything they could to keep me alive, but it looks like that’s not guaranteed, so it’s kind of scary for me,” said Smith, who signed onto the complaint about Washington’s policy. “I’m fearful of how they would treat me and my differences.”

The Back of the Line

Public Integrity analyzed public health crisis policies or guidelines from 30 states—some of which were updated recently in response to the coronavirus, while others have been in place for years.

The policies from Florida and Oklahoma are marked as drafts. A Colorado health department spokesman said the state is working to update its guidelines. Indiana and South Carolina are not using their triage guidelines, according to emails from the states’ COVID-19 Joint Information Centers, but their current response plans have no alternate rationing policies. Guidelines for Wisconsin were posted on the state hospital association’s website; state health department officials did not respond to a question on whether they were official policy. In Texas, a health department spokeswoman said the state has yet to establish a triage policy, but the Texas Hospital Association last week recommended that Republican Gov. Greg Abbott adopt guidelines prepared by hospitals in North Texas in 2014. Public Integrity used the 2014 guidelines for its analysis.

Policies and guidelines in 14 states, including Alabama’s, put patients with specific criteria or diagnoses at the back of the ventilator line in a way disability advocates decry as discriminatory. Alabama, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, Texas and Utah direct hospitals to take dementia into account. In Washington, the state's guidelines say doctors should consider “baseline functional status” when determining whether to move patients to end-of-life care, including “loss of reserves in energy, physical ability, cognition and general health.”

“That’s not, ‘Is this person going to respond well to treatment?’” Wakschlag said. “That’s a judgment about who is more valuable than others that doesn’t really have a place in a medical decision-making process.”

Washington has been developing its guidelines for three years with the help of medical and ethics experts and is currently meeting with disability advocates to address their concerns, said Danielle Koenig, a spokesperson for the state’s COVID-19 Joint Information Center.

“We developed guidance that best reflects the values held by communities across our state,” she said in an email.

After disability advocates filed their federal complaint, Alabama pointed to new guidelines, which give no specific directions on how to ration ventilators but say, “Equipment and supplies will be used in ways consistent with achieving the ultimate goal of saving the most lives.”

The state’s old policy had been “greatly misunderstood,” Arrol Sheehan, a spokesperson for the Alabama Department of Public Health, said in an email. “When there are two or more patients needed to be placed on a ventilator and there is only one ventilator available, a tough choice has to be made and this document was solely intended as a tool for providers in making those hard choices.”

Policies and guidelines in five states—Alaska, Florida, Oklahoma, Vermont and Wisconsin—specify that patients with cystic fibrosis, a genetic lung disease that affects about 30,000 people in the U.S., should be considered lower priority for a ventilator.

But there’s no evidence that cystic fibrosis patients can’t fully recover from COVID-19, said Jessica Rowlands, a spokesperson for the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

“Care rationing decisions should not be based on outdated perceptions of the disease and its prognosis,” she said in an email. Instead, cystic fibrosis patients “should be clinically evaluated and triaged for COVID-19 treatment on a case-by-case basis that is consistent with how other members of the general public will be evaluated.”

Policies in 13 states direct hospitals to evaluate whether patients need “assistance with activities of daily living” or would need more resources than other patients, such as home oxygen or dialysis.

Policies in six states—Connecticut, Florida, Indiana, Kansas, Minnesota and New York—say hospitals should consider taking ventilators away from patients who rely on them in daily life if others need them more, a practice advocates say would discourage people with disabilities from even seeking treatment for COVID-19.

Policies in 16 states took into account how many more years patients are likely to live, beyond their immediate illnesses. Advocates say that could lead to all sorts of discrimination against the disabled, many of whom already have lived much longer than their initial prognoses.

This may be the most controversial issue disability advocates have raised. Hospitals should both try to save the most lives as well as the most years of life when they ration care, ethics expert and law professor Govind Persad and his co-authors argued in the New England Journal of Medicine last month.

Persad told Public Integrity that, if hospitals didn’t weigh underlying illnesses, they would end up saving fewer people, including fewer people with disabilities. But he also said he didn’t know if hospitals following his advice would be violating legal protections for people with disabilities.

“That’s certainly a more unsettled area,” he said.

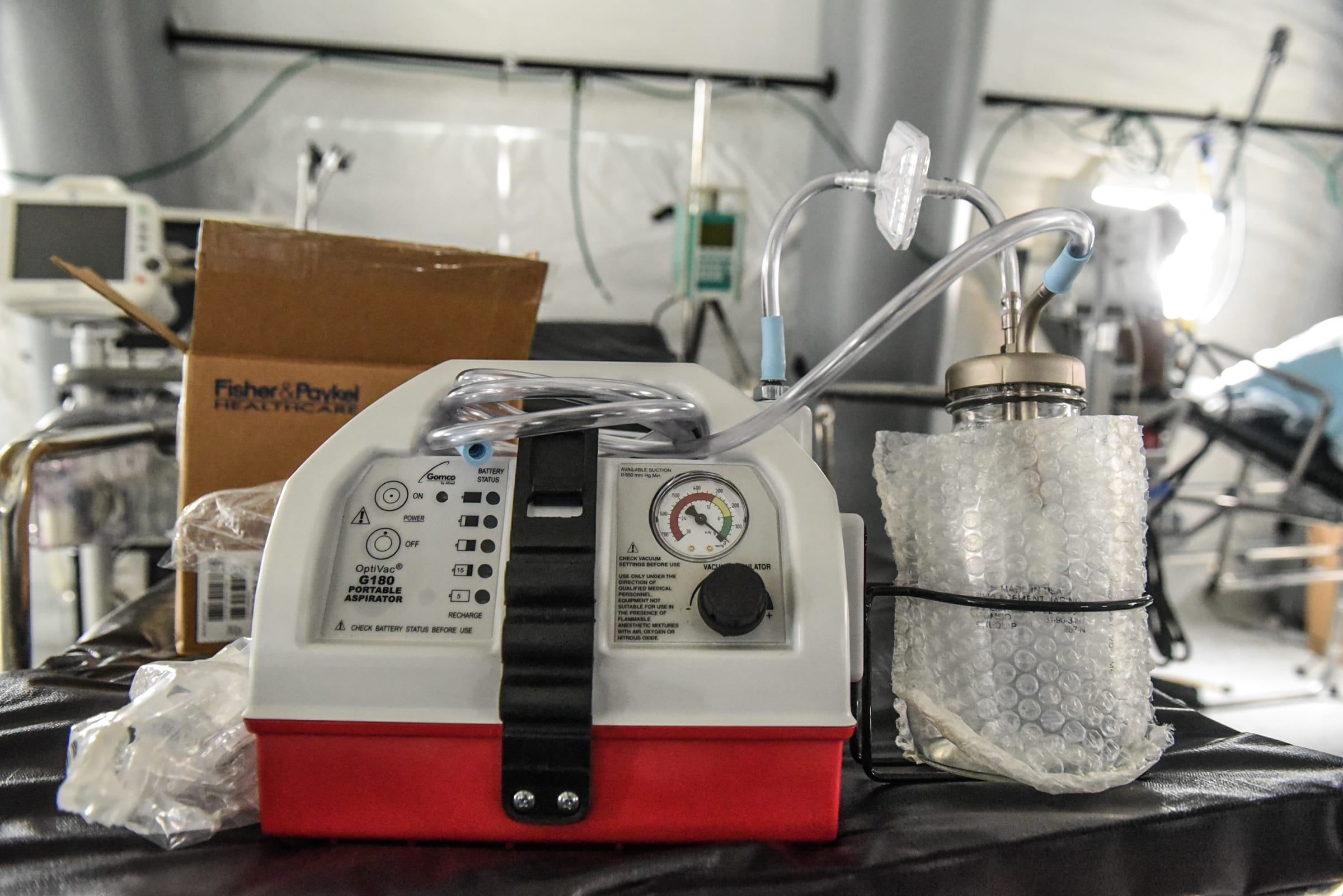

A ventilator in an emergency field hospital to aid in the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City.

Stephanie Keith/Getty

Dr. Douglas White, a professor of critical care medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, started working on crisis rationing plans for hospitals more than a decade ago, disturbed that earlier guidelines excluded patients with certain disabilities or chronic conditions.

Many state policies “contain really concerning language,” he said. “Excluding certain groups of patients from any consideration for ventilators or ICU care really runs the risk of sending the message that are just some lives that are not worth saving.”

White’s “model hospital policy” has been downloaded thousands of times and considered or adopted by hundreds of hospitals, he said. It takes into account patients’ chance of living five more years.

White’s model policy and many state policies also prioritize patients for ventilators based on age or stage of life. Conservative lawyers are already warning states not to deny care to the elderly.

The Dangers of No Plan

Many states still lack plans for how to divvy up ventilators if they become scarce. That also worries disability advocates.

“That seems to ensure even more so that discriminatory decisions could be made if there’s literally nothing that’s guiding these decisions,” Wakschlag said. “We can‘t just let people revert back to their own individual perception of people with disabilities.”

Six states—Arkansas, Delaware, Idaho, New Jersey, Virginia and Massachusetts—said they are working to develop rationing policies.

Jennifer Skjod, a spokesperson for the North Dakota Department of Health, said the state’s hospitals would set their own guidelines.

Six states had pandemic plans or ethics reports that contain little to no practical guidance on how hospitals should ration care. For example, California’s says hospitals in a crisis should focus on “optimizing population outcomes” instead of individual patients, but does not specify how. The California Department of Public Health is “reviewing and updating guidance as needed,” according to an email from the state’s COVID-19 joint information center.

Though experts want rationing policies to be as uniform as possible, no consensus has emerged on whether states or hospitals should take the lead. Some have advocated for a national standard. Both a 2008 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office and a 2009 report from the House Committee on Homeland Security recommended that the federal government do more to ensure standards were set.

In some places, hospitals are scrambling to set their own policies or adapt vague ones from their states. White said he had received calls from about 500 hospitals in the past two weeks seeking guidance on how to implement his model policy.

“In an ideal world, states would put forward really thoughtful policies that could be used by all hospitals in the state,” he said. “Hospitals may not have resources needed to develop a robust policy from the ground up.”

It’s unclear if every hospital is urgently trying to address the issue—or even will be able to—as escalating coronavirus cases make their operations more hectic. Maimonides Medical Center in New York City now has hundreds of COVID-19 patients; one doctor told Business Insider it may need 250 more ICU beds. When asked if the hospital had crisis standards of care in place, spokesperson Eileen Tynion said on March 27: “We’re not there yet.”

Northwell Health, which oversees 19 New York-area hospitals and had 2,800 COVID-19 patients on April 2, does not have a policy related to crisis standards of care, nor does the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada in Las Vegas, spokespeople said.

Two executives from the American Hospital Association, a trade association, told Public Integrity they had received few inquiries from hospitals on how to set rationing policies.

“What I hear from our members is that their primary concern is making sure they’re taking care of the patients coming in their doors,” said Nancy Foster, the association's vice president of quality and patient safety policy. “Other concerns are far behind.”

Foster also said that doesn’t mean triage policies are on the back burner, and that hospitals in normal times have ethics committees and organ transplant committees meant to guide physicians’ most difficult decisions.

But organ transplant committees also raise red flags for disability advocates. A 2019 report from the National Council on Disability found that people with disabilities were often discriminated against in organ transplant decisions.

Across the board, ethics experts and disability advocates agree that, whatever the rationing policies are, they should be clear to patients.

“Having no clue about what the standards are going to be is incredibly frightening, and I don’t think I can responsibly tell people not to worry about that,” said Alison Barkoff, director of advocacy at the Center for Public Representation, which defends disability rights. “This is the thing that’s keeping them up at night.”

But officials in some areas are already shrouding policies in secrecy.

Pennsylvania refused to release the interim rationing guidelines it had given to hospitals to use and adapt as needed. Public Integrity analyzed the state’s guidelines dated March 22, as obtained by The New York Times. Nate Wardle, a spokesperson for the Pennsylvania Department of Health, said the guidelines were not yet finalized and also could not be obtained through a request under the state’s freedom of information law.

A University of New Mexico Health System spokesperson said the organization had a pandemic plan it was not releasing. California’s MemorialCare Long Beach Medical Center is still reviewing its policy, said Chief Medical Officer James Leo, and did not release it. A UCLA Health spokesperson said the hospital system had adopted “guiding ethical principles” but did not release them.

In Alabama, Foster and his family already had one scare when he came home from a conference in early March and started coughing. He was tested for COVID-19. It was negative. But the family is being careful.

“I have a disability,” Foster said. “I have a right to live.”

This story is from the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit, nonpartisan investigative media organization in Washington, D.C.