Paralysis might one day be as easy to cure as a single injection of a drug, if some promising new results stand up to scrutiny. Scientists at Northwestern University reversed paralysis in mice with spinal cord injuries by injecting them with a self-assembling gel that can repair tissues.

We don’t yet know if the findings, published in the journal Science, will translate over to humans. But for the nearly 1.5 million people in the U.S. living with paralysis caused by spinal cord injuries, the study provides a glimmer of hope, especially for a condition that less than 3 percent of people fully recover from.

“Currently, there are no therapeutics that trigger spinal cord regeneration,” Northwestern's Samuel I. Stupp, who led the study, said in a statement. “Our body's central nervous system, which includes the brain and spinal cord, does not have any significant capacity to repair itself after injury or after the onset of a degenerative disease.” Experimental treatments like stem cells or gene therapy have never yielded very good results.

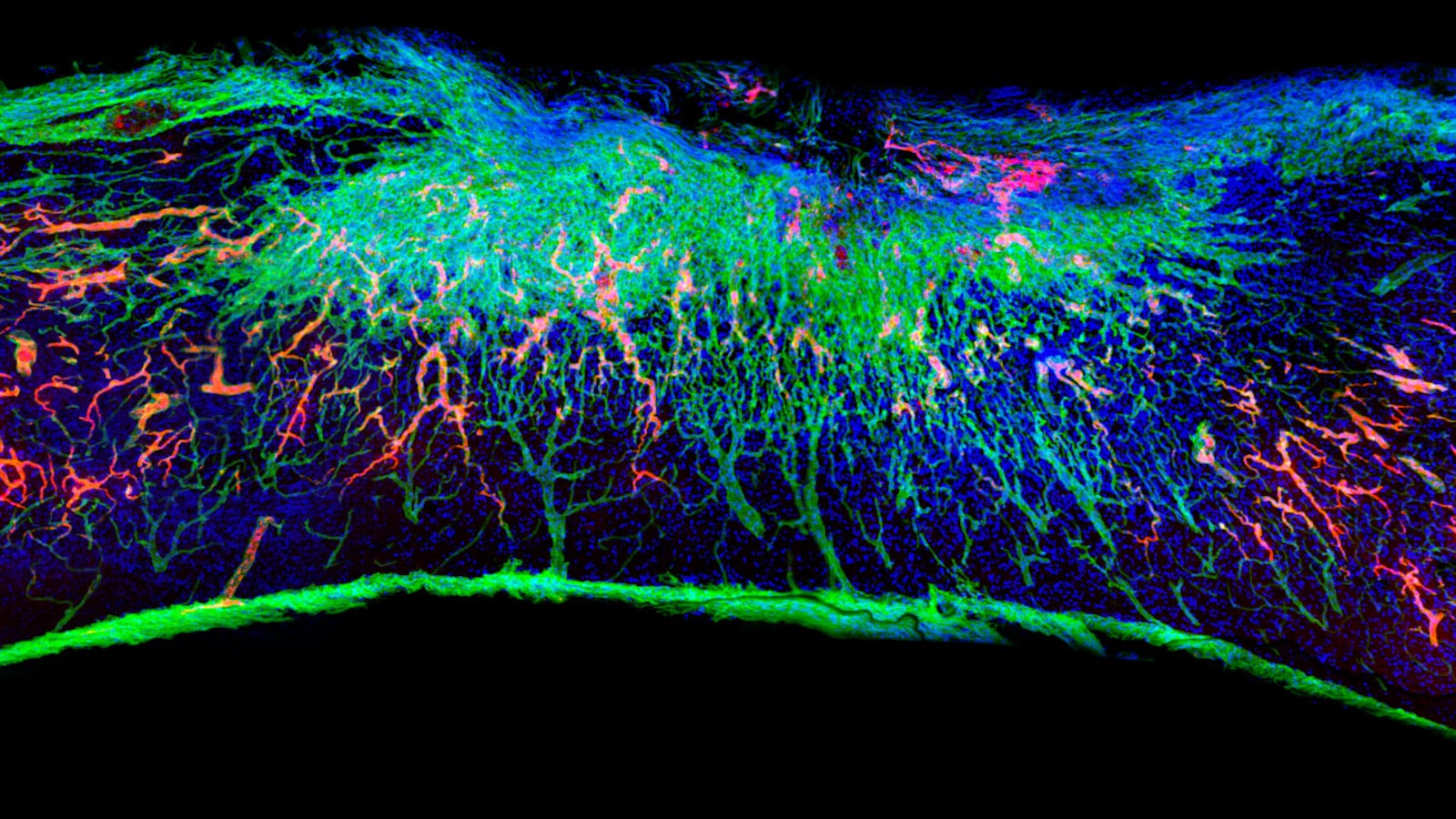

The new gel is designed to act as a kind of scaffolding for cells in the spinal cord and make it easier for them to grow. It’s made of individual protein units that are able to automatically bind together into long chains in water. Within the body, a network of these chains can mimic the extracellular matrix of the spinal cord to give cells a structure on which to grow.

The gel also works by sending biological signals that trigger nerve cell and blood vessel regeneration, restoration of essential fat insulation known as myelin around nerve cells, and removal of scar tissue that could physically bar cell regeneration.

The Northwestern team injected a single dose of the gel at the site of spinal cord injuries into mice whose hind legs were paralyzed. Within four weeks, the paralyzed mice were able to walk again. Within 12 weeks, the gel’s materials degrade and disappear from the body completely, without any noticeable side effects.

And to boot, the study authors say the gel is fairly inexpensive to produce.

Scaling up mice demonstrations for people is a difficult process, but the authors are moving full speed ahead. “We are going straight to the FDA to start the process of getting this new therapy approved for use in human patients, who currently have very few treatment options,” said Stupp. He added that the gel might also have applications in helping repair brain tissue affected by a stroke or neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

If future studies pass muster, it could prove to be a breakthrough treatment for an array of brain and nervous system conditions.