His family would not be notified for nearly a week, but on the afternoon of May 14, 2013, a young man named Kwesi Sample drowned off the coast of Holden Beach, North Carolina. The 21-year-old was participating in a GPS-guided scavenger hunt known as “geocaching” with other young adults in his church, an Ohio-based megachurch called Dwell. The group was attempting to swim several hundred meters to locate a particularly difficult “cache,” but by the time they realized the distance was too far, it was too late. “As they swam across the ocean inlet, Sample began to struggle and went underwater,” an Ohio appeals court later wrote. “The others were unable to save him.” (The church has said in court filings that it notified Sample's family within hours of the incident.)

In a wrongful death suit that followed, Sample’s family took aim at Dwell, alleging that church leaders were negligent in organizing the activity. But their complaints went well beyond the day’s tragic events. In various legal filings, the family claimed church leaders exercised far-reaching authority over its members, stretching past Sunday sermons and into almost every corner of their lives. (The church called this idea “absurd” and said Sample’s lawyers took their teachings out of context.) It purposefully recruited impressionable young members, the family claimed, and taught them to blindly follow leaders who were “chosen by God.” Shortly before his death, they said, Sample had even moved into Dwell group housing to receive “spiritual teachings” and “guidance on how to live and worship” from its leaders.

“A lot of people who leave [Dwell] feel [like] they’ve been isolated; they feel like they’ve been manipulated,” Adam Richards, an attorney for the family, told The Daily Beast in a recent interview. “And then one day they wake up. And sometimes it’s too late, and sometimes it’s not.”

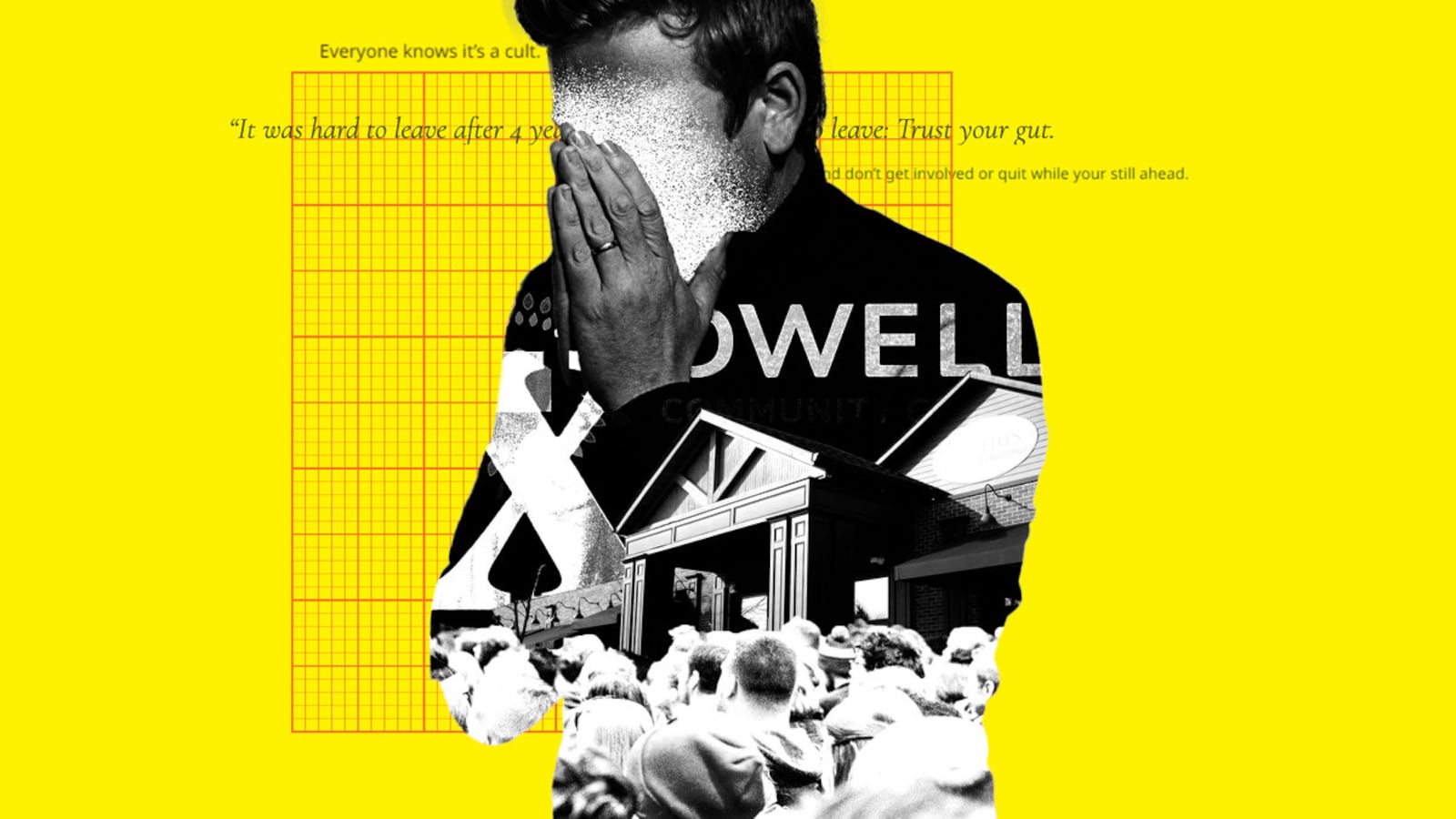

In recent years, a growing movement in Columbus, Ohio, has started sounding the alarm on the church, claiming it is manipulative, controlling, even dangerous. Hundreds of aggrieved former members have formed an online support group; nearly 200 have submitted testimonies to a local blog. The church even changed its name two years ago—from “Xenos,” which it had used for decades, to “Dwell”— though its leaders claim the move was unrelated to the bad press. Still, there has been no discernible response from public officials.

Over the last two months, The Daily Beast interviewed 25 former Dwell followers, whose membership spans nearly four decades. While the details of their experiences differed, the result was the same: Dwell, they said, was a church that drew them in when they were young or lonely, showered them with attention and compliments, and quickly turned dark. A church that pressured them to relinquish all their free time, to cut ties with their outside friends and family, to move into group houses with their fellow members. A church that dictated who they could date, where they went to school, and how they groomed their body hair. A church that pressured them to stay in abusive marriages and blamed them when they were raped. A church that warned them that walking away from Dwell would be walking away from God.

What they were describing, many of them said, was not a church at all, but a cult.

In an interview with The Daily Beast, Executive Pastor Brian Adams rejected this label, calling it “an anti-Christian slur.” The church, he said, was just “a group of committed Christians who are gathering regularly to pray and study the Bible and enjoy community.” Everyone was invited to participate up to their own comfort level.

Executive Pastor Brian Adams says the church is “a group of committed Christians who are gathering regularly to pray and study the bible and enjoy community.”

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon, Emily Shugerman/The Daily Beast/Getty/YouTube"We absolutely want everyone who walks through our doors to have a great experience,” he said. “What it comes down to is understanding what the Bible teaches, and do you want to follow it or not?”

Of the allegations of cultishness and spiritual abuse, he added: “It's sad to hear, but we can understand [it if] someone says, ‘What you're doing there, we want to pursue something different.’”

Dennis McCallum, the 70-year-old founder of Dwell, is thoroughly convinced that his church is fighting a war with Satan. In his book, “Satan and His Kingdom”—one of 14 books he has published on Christianity—McCallum claims that the devil is a living being, and that a “spiritual war” is raging against him around the world. He claims Christians must act as soldiers, ready to endure extreme suffering, sacrifice their possessions, and follow their leaders’ orders. Soldiers in the spiritual war, McCallum writes, “aren't free to show up only when they want to.” On the battlefield, “exertion may often be to the point of utter exhaustion.”

Former members who spoke to The Daily Beast say this pressure to be constantly “on” for Jesus pervades Dwell. New members start by attending Sunday sermons called “central teachings” and weekly Bible studies called “home churches,” but they are quickly urged to participate more and more: in sex-segregated “cell group” meetings; meetings with a spiritual counselor known as a discipler, and leadership courses required to advance in the church ranks. There are meetings for new parents, college students, people in recovery, people who have lost a loved one or were sexually abused as children. Members can easily find themselves attending a different Dwell event every day.

The meetings are not an explicit requirement, but members say the push to attend them—to be an active member of the church, rather than a “pew-sitter”—is intense.

“[I found myself] going to six meetings a week,” said ex-member Justin Stapleton, 36, who joined the church about 15 years ago. “The whole time they’re telling me, ‘You’re not committed enough. You’re not committed enough.’ But I’m spending all my time there.”

Ex-member Callie Nicholson, a 25-year-old nutrition student and behavioral therapist, told The Daily Beast she struggled with an eating disorder while in Dwell. When her treatment program suggested she attend fewer church meetings in order to focus on recovery, she said, her home church leaders were furious. They insisted that her therapists didn’t understand her because they were “of the world”—Dwell terminology for anything outside the church. (In a blog post after this story was published, Dwell pastor James M. Rochford said that pastoral staff “spoke with the leaders of this young woman’s group, and heard a different account.”)

Another woman, who asked to be anonymous for fear of retribution from current church members, said she was pressured to stop visiting her family once a month because it conflicted with Friday cell group meetings and Sunday house meetings. Members told her she was being “unloving” and “wasn't serving the girls in the group well enough,” she said. She cut back on the time with her family.

Younger, unwed Dwell members are prodded to move into “ministry houses” that sleep up to four per room. (Stapleton said a house leader told him the point of the cramped quarters was to prevent residents from masturbating.) Once there, members are expected to spend most of their free time socializing with house members or evangelizing to potential recruits. Studies are an afterthought; at least one person said they considered changing their major to something less rigorous to meet the demands of the church. Several former members told The Daily Beast they even turned down offers to prestigious out-of-state colleges in order to live in the ministry houses.

Madeline Beal, a 24-year-old social work student who was born into the church, said she rejected a scholarship to the Art Institute of Chicago to attend Ohio State University at the behest of Dwell leaders and peers.

“What people said to me word for word was just like, ‘God has a plan for you here, and he’s put you here, and you can’t leave,’” she said. “That would be disobeying God."

The pressure to share personal information in the ministry houses—in order to hold each other “accountable,” as the church likes to say—is enormous. Beal said a common activity at house meetings was a game called “Oys, boys and joys,” where members shared one good event, one bad event, and one romantic event that happened to them that week. If the house leader felt like one member didn’t open up enough during the activity, she said, they would follow up later to pry out more information.

Other members said this kind of personal information-gathering is common, even outside the ministry houses. BJ Brown, 46, a former high school group leader, said she met weekly with two church leaders who tried to get her to reveal personal details of the students’ lives. At one meeting, she said, an elder asked her whether she thought another leader in her group was lesbian. (Adams, the executive pastor, said in an email that “gossip is a sin condemned in the bible and it’s not something we want to see any of our leadership practicing.”)

"We’d just sit there and talk about people’s personal problems and issues like it was a normal thing to do,” Brown recalled. “I can’t believe how freely the leadership—including myself when I was there—openly talked about people’s raw issues.”

Members said the group inserted itself into many other areas of their lives, from who would be in their wedding to how they groomed themselves. (Two women said they were told by other church members to shave their armpits because body hair was seen as a potential turnoff for recruits.) Many former members who spoke to The Daily Beast said they were strongly discouraged from spending time with friends outside the church unless they were actively recruiting them. Even spending time with Christians in other churches, they said, was seen as a waste of time because they were less likely to be recruited to Dwell.

Ex-followers said the church also wielded outsize influence on their dating lives. Oliver Long, 36, said McCallum often invited people over to discuss who was seeing whom, whether they were good for each other, and how the church could interfere if not. He said McCallum kept a list of people deemed “spiritual enough” to be dating, which he shared openly. Numerous other members told The Daily Beast they were told not to pursue someone inside Dwell because they were not deemed “ready” to date, or because the other person was not spiritual enough for them. (Adams said the Bible doesn’t say specifically who you can and cannot date, and “in our fellowship we don’t teach anything like that.” (After publication, the church said McCallum denied keeping such a list.)

The ex-member who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution said she started dating someone she met online toward the end of her time at the church. She said fellow church members cautioned her against dating someone who was “of the world” and more likely to “live in sin.” Her former discipler, she said, instructed her to give her boyfriend an ultimatum: Join Dwell in the next two months, or she would break up with him. The woman refused and left the church because of it.

In an email, Adams said the church did not require anyone to spend a certain amount of time worshiping or hanging out with other members, and that anyone who felt “unfairly pressured” should report it to the church. “Many of the allegations brought forth seem to be people who left the church because living according to the values and precepts of the Bible is hard or because they felt pressure to do more,” he added. “We can’t control how people feel.”

But Dr. Janja Lalich, a sociologist and prominent cult expert, said the high levels of control at Dwell were typical of a cult. While the group may not have a classic charismatic leader, she said, its adherence to a single, strict ideology still dominates members’ lives. Its network of home church leaders are deputized to enact that ideology, she said, isolating them from the outside world and leaving them in a “bounded reality.”

“People are giving up their own autonomy. They’re giving up their own decision making. They’re pawns,” she said. “And if they think about leaving then they’re going to lose everybody they know and their family.”

She added: “It’s classic cult stuff.”

McCallum founded Dwell as a student at Ohio State University in the 1970s, with a pack of other hippies who wanted to study the Bible but buck the traditional church. (He is still fond of saying he found God in a jail cell after being arrested for marijuana possession.) To this day, the church maintains some of its anti-establishment bent; members attend sermons in jeans, drink openly in home church, and smoke like chimneys.

But there is an area in which former members say the church remains extremely regressive: women.

Nicholson, the woman who struggled with an eating disorder, told The Daily Beast she was raped at a gathering of non-Dwell members in 2020, when an attendee stuck his hands down her pants and assaulted her when she froze in fear. For weeks, Nicholson blamed herself for not saying “no” and believed the assault was her fault. She finally confided in a friend, who told her that what happened was rape and encouraged her to speak with a discipler. (The Daily Beast spoke to this friend, who confirmed Nicholson’s version of events.) When she finally worked up the courage to do so, Nicholson said, the discipler advised her to pray and repent. Later, the discipler urged Nicholson to confess her “sins” to her entire cell group.

“I’d be like, ‘What do I have to confess about? I was raped,’” Nicholson recalled of their conversations. “And she’d be like, ‘Well, we both know you had a part to play in this.’”

In his email, Adams said Dwell leaders had interviewed Nicholson’s roommates after the incident and urged her to call the police. He said a mentor later “encouraged her to open up to others about how she was doing and to let God help her with the personal problems she was facing.” Nicholson felt like she was being confronted for being assaulted, he said, “but that wasn’t the case.”

But another woman—the ex-member who asked to remain anonymous—told The Daily Beast she, too, was sexually assaulted while a member of Dwell. The woman said she was assaulted by someone she thought was a friend while at a wedding out of state in 2018. (Another friend who spoke to The Daily Beast confirmed that she told her about the assault immediately after returning home.) When she told her home church about the incident, she says, another member asked her whether she’d actually fallen into “sexual sin” and was inventing the assault to cover it up.

Other members were more supportive, she said, but that didn’t stop leadership from pushing her to return to church meetings before she was ready; from telling her not to let what had happened dictate her life. In one particularly memorable moment, she says a leader told her:

“God has a plan for your pain.”

The church says it strictly bars the leaders of high school groups from dating their teenage disciples. But one ex-member, Katie Oliver, said she started dating her 20-year-old high school group leader when she was just 17. When the church found out they were sexually active, she said, her boyfriend was kicked out of his ministry house but allowed to stay in fellowship. Oliver, meanwhile, was forced to go through a process called “admonishment,” in which 10 to 15 other women—including her mother—called her into a room and “took turns basically ripping me apart,” she said.

A week or two later, when Oliver attended her weekly cell group meeting with other girls her age, a group leader took everyone for ice cream afterward. Oliver had to stay behind.

“I very much felt like I was wearing a scarlet letter,” she said. “I was definitely targeted to the point where I left the church.”

Because the church does not allow pre-marital sex, former members said, there is pressure to get married young—and quickly. But the church also heavily opposes divorce, allowing it in only three circumstances: adultery, abandonment, or death. Two women told The Daily Beast they stayed in abusive relationships for years because church leaders counseled them to stick it out.

One ex-follower, now in her mid-forties, said she married another Dwell member when she was 23, in a rushed wedding the weekend after her nursing finals. She says her husband quickly became controlling and prone to anger toward her and their three children. But when she went to church leaders, she said, they told her to try to make things work.

“That’s all the counsel I kept getting was, ‘Suffering is part of being a Christian, and marriage is hard. You just have to endure the suffering,’” she recalled.

“Well, it was emotional abuse,” she added. “It was terrible. I was having panic attacks.”

When she eventually did file for divorce, the ex-member said, she avoided Dwell meetings for several months. When she returned, she says, she attended just one or two meetings before a group of church leaders pulled her aside and told her what she was doing was a sin. They instructed her to salvage her marriage or consider leaving the church. She never went back.

Another member—who asked that we use only her first name, Amy—said she joined the church in 2006 at the request of her then-boyfriend. Soon after the two wed, she says, her partner became extremely controlling: hiding all the passwords to all their joint accounts, overseeing her spending, and tracking her whereabouts obsessively. (His daughter from another marriage, who remains close with Amy, confirmed he was controlling and overly critical of both his wife and children. Police records show officers were called to the home several times to mediate disputes between Amy’s husband and his kids.)

When Amy went to Dwell counselors about the issue, they advised her to keep working on her marriage. Once, at her breaking point, she asked a church leader how much longer she was supposed to endure this treatment. She says the leader told her: “Jesus endured suffering at the hands of his abusers until His death. It’s not about how you are loved, but how you love others that matters.”

Amy says she responded: “And I’m not Jesus.”

Adams said the church would never remove a member for divorcing someone who was physically or sexually abusive, but that it does ask members to save their marriage “whenever possible”—through counseling, marriage classes, and reading relevant Bible passages. He added: “This is the proper path and only seems strange through the lens of secular society rejecting the most basic tenets of Christianity.”

Members say the church also strongly opposes same-sex relationships. (Adams declined to comment on this directly, saying only that sex outside of marriage, of any kind, is a sin.) One ex-follower, Seth Grover, said he watched as a high school senior confessed his feelings of same-sex attraction to his entire ministry house before he moved in. At house meetings afterward, Grover said, the member reported that he was “working on” his feelings and that his goal was to feel attracted to and marry a woman. When Grover confessed his own feelings of same-sex attraction to a discipler, he said, the leader told him he was deluding himself and wasn’t actually queer.

Beal said that multiple members of her college group were also made to confess their feelings of same-sex attraction, including one woman who was forced to reveal her crush on Beal. When the young woman came to her room in the ministry house to confess, Beal said, there was no expectation that anything romantic could come of it. “She was just confessing this as a sin because she had to,” she recalled.

Members who do not follow the church’s rules on sexuality, premarital sex, or any other number of sins can be removed through a process called “disfellowshipping.” Former members said this usually involves a formal meeting in which the sinner’s transgressions are laid out—in occasionally embarrassing detail—before their entire 20- to 40-person home church. The member is given a chance to respond before their fellow congregants vote on whether to kick them out.

Adams framed these meetings as “a Biblical process, not a punishment”—a last resort to convince unrepentant members to take responsibility for their actions. But former members say it is an intentionally brutal process that the church uses as a cudgel to keep members in line. As former member Mark Kennedy put it: “These people are being emotionally brutalized. It’s a public shaming.”

Some members said they had been removed for sins as minor as not attending enough meetings and not having a positive attitude. Three said they were excommunicated for engaging in pre-martial sexual activity; two said they witnessed others get excommunciated for being gay. (Adams refused to give the church’s stance on openly gay members, saying only that “everyone is loved by [God] dearly.”)

When a member is removed, former members say, their fellow home church members are instructed not to speak to them—a devastating outcome to those whose entire social lives revolve around the church. (After publication, Rochford denied teaching this and said the church “continue to keep in contact with people who have been removed from fellowship.”) Two women told the Daily Beast they contemplated suicide after being ousted.

Megan McGowan, a 33-year-old accessibility specialist who joined the church in 2012, wound up in a two-week partial hospitalization program after she was disfellowshipped in 2016 for repeatedly engaging in “sexual sin” with her boyfriend. Adams said members who show remorse at their meetings are given the opportunity to repent and return, but McGowan said she begged to stay in the group and was told it wasn’t enough. One member of her home church, she said, told her she needed to hit “rock bottom” before her heart could change.

“Rock bottom for a suicidal person is death,” McGowan said.

Eight years after Kwesi Sample died off the coast of North Carolina, an Ohio appeals court ultimately sided with the church, ruling that it was not obligated to protect its members from the dangers of open-water swimming. But the years-long legal battle lost the church some goodwill, even among its members. Sample was well-loved by the congregation, and community members were outraged when Sample’s family alleged that no one from Dwell had contacted them until a week after his death. (The church said in court filings that it contacted Sample's family members by phone in the hours after his death and spoke to his grandmother the day after he passed away.) Later, the church tried to argue that the beach trip was not a Dwell-sponsored event at all, but a “personal vacation”—which multiple former members said felt duplicitous.

Sample’s mother, Raynette Cornish, died before the case was resolved. Richard, the family’s lawyer, said she often talked about how she felt the church had taken her son away from her even before he died. After Sample joined Dwell, she said, he spent less time with his family and seemed less open-minded and accepting.

“She saw changes in him that she didn’t think were consistent with the last 18 years of his life,” Richard said. She told him: “I don’t want another parent to ever lose a child, let anyone lose a child like I did.”

Since Sample’s death, an increasing number of Dwell defectors have taken up the same cause. Several launched a Facebook support group in 2018, which has since swelled to nearly 450 members. They generally use the group to vent and console each other, but they occasionally share ideas for action. A number of members—including Gail Burkholder, one of the group’s administrators—participated in a Columbus Dispatch article criticizing the church’s 2020 rebrand. (Burkholder likened the name change to putting “lipstick on a pig.”)

Mark Kennedy started his own website in 2018, after watching his sister’s membership tear the family apart. (The website, called “Xenos is a Cult,” was started before the church changed its name to Dwell.) Kennedy, 24, intended to use the site as a catchall for various writings about the church scattered across the internet. But soon after it launched, he said, former members started sending him their own testimonials to post to the site. He has so far published 185.

A local NBC station published a series of seven articles critical of the church this winter, and a documentary is reportedly in the works. Still, authorities in Columbus have remained largely silent about the allegations against Dwell. Both the city council and the University Area Commission, an advisory board that was previously critical of the living standards at ministry houses, declined to comment on the record to The Daily Beast. The Franklin County Sheriff’s Department did not respond to a request for comment.

Kennedy says he is not looking to get the church shut down, only to warn others about the dangers of joining. Others said they would just like the church to admit the error of its ways and commit to change. But Burkholder, whose ex-husband still works for the church, said she wasn’t holding out hope.

“My goal is for my ex-husband to be unemployed, [and for] the whole place to go away and stop hurting kids in Columbus, Ohio,” she said.

“I’m 60 years old, I’m not an optimist,” she added. “I know what a toxic organization looks like.”

Editor’s note: The Daily Beast gave Dwell leadership the opportunity to respond to all allegations in this story before publication. After publication, the church released a lengthier response. Some of those comments have been added to this piece throughout.