David Shields is done with fiction, at least as you and I probably know it. After beginning his career as a novelist, the 56-year-old Shields, over the last decade and a half, has drifted toward loose, essayistic forms that tear down the walls between fact and fiction. (In fact, he claims that those walls never existed in the first place.) This “project”—a favored Shields word—crested in 2010 with Reality Hunger, a book-length collection of quotations and aphorisms cobbled together to argue that contemporary fiction should embrace hybrid genres, the instability of truth and memory, the essential falsity of the novel, appropriation, and so on.

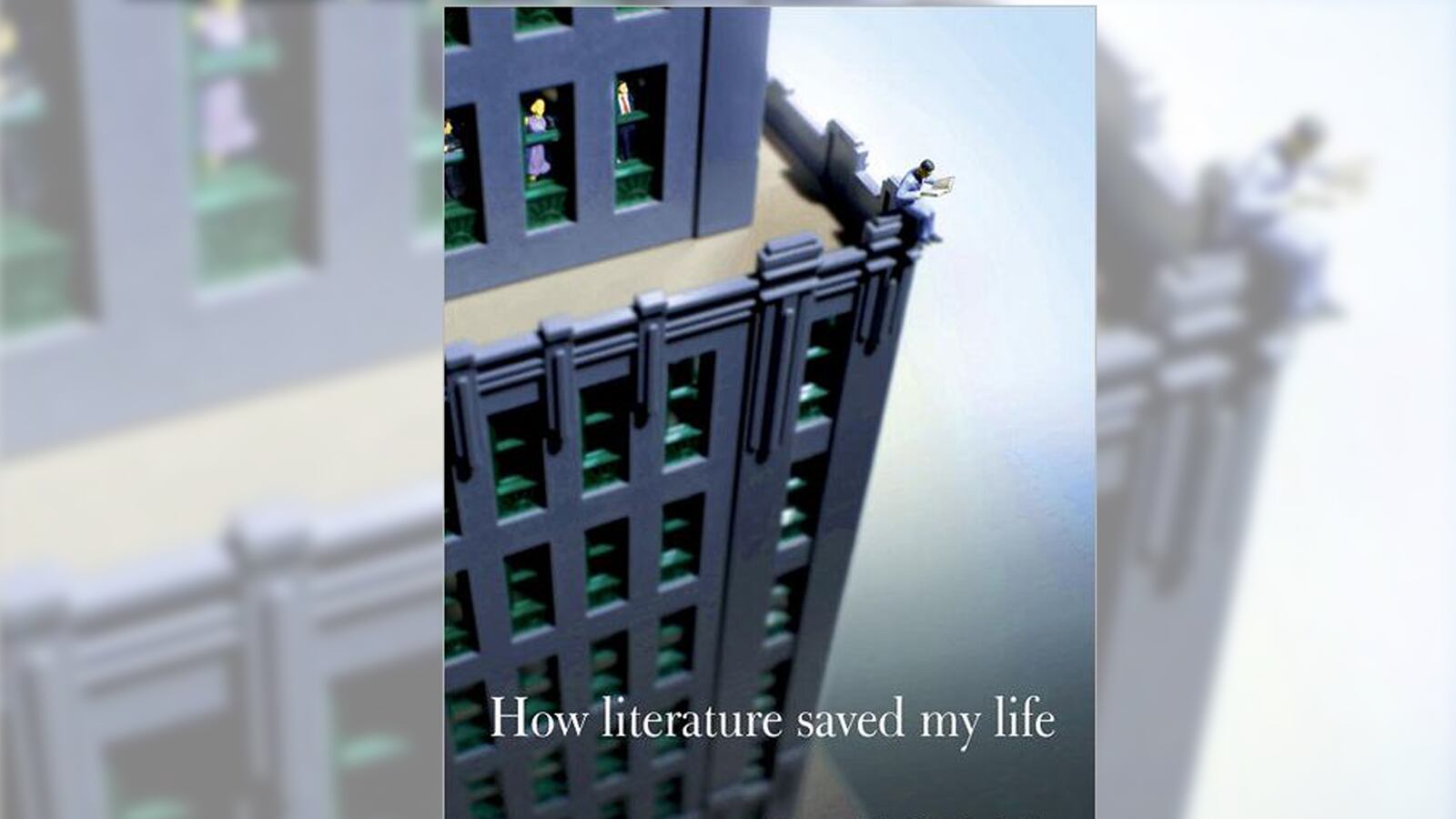

Shields has been a worthwhile polemicist (Reality Hunger was subtitled A Manifesto) for the sometimes buttoned-up world of literary fiction. But what began as a matter of taste and then matriculated to an argument over aesthetics has now become ideology. In his latest book, How Literature Saved My Life, he recapitulates much of Reality Hunger’s argument while falling into a deep, mawkish solipsism, one that leaves him unable to recognize why anyone may have an interest in the vast range of fiction that centuries of literary culture have produced. More troubling is, he has become so convinced of his own beliefs that he seems to have little desire to convince others of them; they have instead ossified into dogma.

But let's begin at the beginning. What does Shields believe, and what is this new book about? Ostensibly, it’s a kind of memoir, but the personal revelations are few. When they do come (mostly scattered in the book’s first hundred pages), they’re appealing and heartfelt, albeit abridged. We learn about his manic-depressive father, who “craved” electroshock treatments: “I'll never forget his running back and forth in the living room and repeating, ‘I need the juice,’ while my third-grade friends and I tried to play indoor miniature golf.”

We learn that, as a stutterer, Shields thought writing would give him the ability to control language in a way that his speech wouldn’t allow (he used that material for his novel Dead Languages). And he tells us about the time he wrote on a wall at Brown University’s library, “I shall dethrone Shakespeare.”

That immense ambition is gone, replaced by detachment and lassitude. Has Shields changed, or has the world around him, literature included? Now he calls himself a “writer of wayward nonfiction.” For years he has been devoted to collage, “in which tiny paragraph-units work together to project a linear motion” and where the work’s “thematic investigation is manifest from the beginning.”

The risk with collage is that it can seem slapdash or myopic, its meaning opaque to anyone but the artist. How Literature Saved My Life is such a work, a collection of brief meditations, most just a page or two, organized around concepts like life, death, and literature. They are long on sentiment, but short on argument or narrative.

That’s because Shields sees little use for narrative anymore. It’s one of fiction’s cynical fabrications that must be abandoned. He can’t open a novel now without seeing its entire superstructure—characters, plot, story, dialogue, the setting of a scene—as an enormous charade. It’s but a reminder of the insufficiency of language itself, of our inability to communicate and say what we really mean. Hence Reality Hunger, which attempted “to put ‘reality’ within quadruple quotation marks.”

But Shields has hardly found a worthy replacement. The endless succession of quotation marks is its own contrivance, a scrim between Shields and the world. And he’s made the mistake of universalizing from his experiences, as if he doesn’t represent just one strand of current literary thinking, but the wise vanguard that we would do well to follow. He also doesn’t help his cause by filling his book with mealy pronouncements like this one: “I'm very drawn to the way in which a life lived can be an art of sorts or a failed art and a life-lived-told can be art as well.”

He wants “work that, possessing as thin a membrane as possible between life and art, foregrounds the question of how the writer solves being alive.” “Books that simply allow us to escape existence” are “a staggering waste of time (literature matters so much to me I can hardly stand it).” That literature can serve many masters—that it can be escapist or entertaining, that it can tell us something about how other people live, particularly in foreign cultures, or that there can be joy in decoding a great writer’s artifice—doesn't seem to have occurred to him.

Shields confesses that he feels detached from his own emotions. “I don’t know what’s the matter with me,” he says, “why I’m so adept at distance, why I feel so remote from things, why life feels like a rumor.” He finds that “it’s increasingly hard to have actual feelings anymore.” Shields seems at the very least bored and likely depressed. Neither is an enviable condition, or uncommon for a writer, but there’s nothing interesting in how Shields addresses them. When he calls Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage “a thinking person's self-help book,” one must wonder if we’re dealing here with a failed attempt at the same.

As a cultural force, the novel may be in recession compared to past halcyon days (the speed of its retreat is still being measured). But Shields slips into sophistry when he says that “the key thing for an intellectually rigorous writer to come to grips with is the marginalization of literature by more technologically sophisticated and thus more visceral forms.” Still, he goes on:

The novel is an artifact, which is why antiquarians cling to it so fervently. Art, like science, progresses. Forms evolve. Forms are there to serve the culture, and when they die, they die for a good reason—or so I have to believe, the novel having long since gone dark for me ...

This is isn’t the language of a writer or a critic. It’s business-speak, seasoned with a dash of futurism. Why is technological sophistication “more visceral”? That is no more true than the notion that simpler technologies are somehow more authentic—the telephone more “honest” or direct than email, for example. The “so I have to believe” gives him away: he’s trying to convince himself of something.

The man who once wanted to dethrone Shakespeare now argues that “the next Shakespeare will be a hacker possessing programming gifts and ADD-like velocity.” He says that's “more or less how the original Shakespeare emerged—using/stealing the technology of his time (folios, books, other plays, oral history) and filling the Globe with its input.” This is nonsense. Shakespeare appropriated others’ stories and shards of history, but that doesn’t mean that he didn't have genius or originality. He put in the work. And Shields can’t have it both ways: on one hand he denies the appeal of traditional fiction while then invoking Shakespeare and Proust as totemic figures.

“I am not that computer programmer,” Shields admits, without being more specific about what dream machine his coder might invent. (Programmers make convenient avatars for this kind of vague prophecy.) “How, then, do I continue to write? And why do I want to?”

These are worthwhile questions, usually considered before sidling up to the word processor. A Freudian might also ask if Shields has sublimated his anxieties over achieving literary greatness into the feeling that fiction itself is largely worthless. Most of us—inevitably and painfully—fall short of our ambitions. But that failure, and the fruits of our efforts, has meaning. Often, it's the most important thing.