For months the United Nations insisted it was in full accord with the Lebanese government’s opposition to opening refugee camps in Lebanon for the influx of an estimated 1 million refugees from war-torn Syria, but in a dramatic and unadvertised reversal of policy, U.N. authorities are now proposing establishing a dozen major camps—a move reflecting a grimly deteriorating humanitarian crisis.

The decision, which some veteran aid workers criticize as coming far too late, will place the U.N. at serious odds with Lebanese political leaders and especially the militant Shia movement Hezbollah, which is a key ally for President Bashar al-Assad.

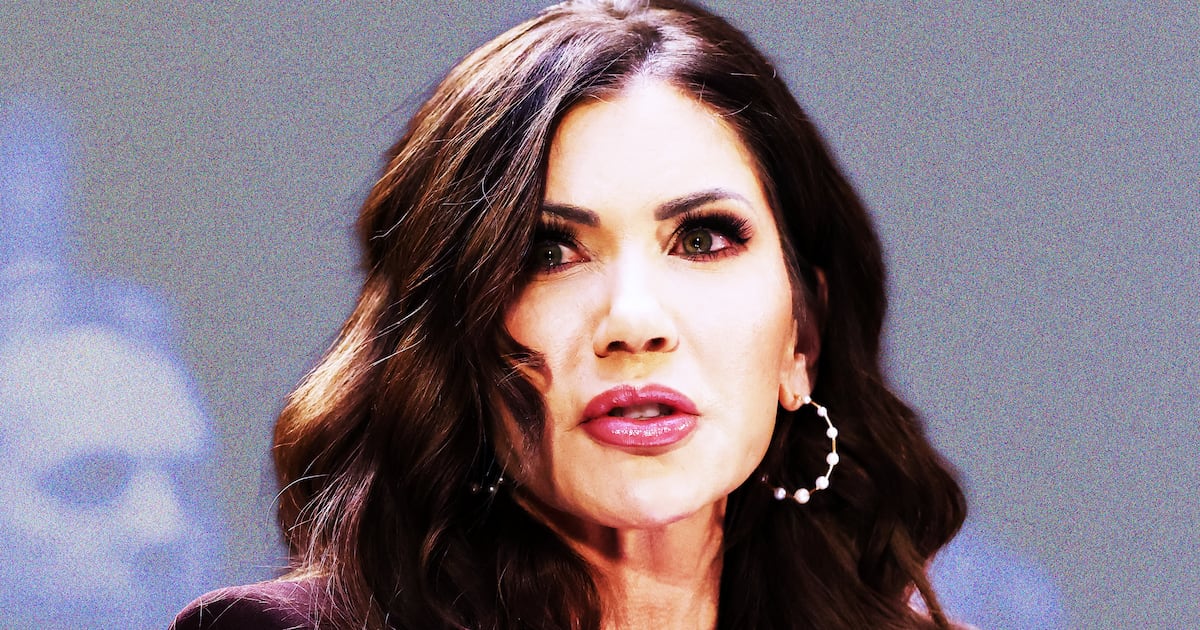

Hezbollah has adamantly refused to accept the establishment of camps, fearing the mainly anti-Assad Sunni Muslim refugees from Syria will remain long-term. Just this month, Ninette Kelley, the UNHCR chief of mission here, insisted that not building refugee camps was the right strategy and argued Lebanon was “a model for dealing with refugees.”

But that two-year-long approach is about to be abandoned for a 180-degree reversal, exposing the U.N. to criticism that it misunderstood the scale and nature of the crisis and compounded refugee suffering.

According to documents leaked to The Daily Beast, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is planning a first camp at Chaat in the northern Bekaa Valley, a majority Shiite Muslim area “within Hezbollah’s area of influence.”

U.N. officials note in the documents they still have to receive the sign-off from the Lebanese government, but with the refugee crisis deepening and the government desperate for aid, they seem hopeful a deal will be reached. In a record-breaking $5.1 billion humanitarian appeal launched this month by the U.N. for the Syrian crisis, the largest portion of $1.2 billion is earmarked for Lebanon. How Hezbollah will react to the opening of camps is unclear.

The U.N. refugee agency hopes to follow up quickly with two more camps in Hezbollah-dominated west Bekaa in the towns of Joub Janine and Tall Znoub, and it wants to have eventually 12 camps able to shelter 100,000 refugees each, according to the U.N. documents and briefings by UNHCR officials of aid agencies in Beirut. This would bring Lebanon in line with the U.N.’s camp-based strategy in Jordan and Turkey. Six other camps able to house 15,000 refugees are also being planned.

For the past two years, an increasing number of Syrian refugees in Lebanon have had to house themselves, and those registered with the U.N. have been receiving only a meager allowance in the form of a $30 food voucher per family member each month. Many have relied on rapidly depleting savings or unpredictable help from irregularly funded private relief organizations and poor local host communities.

With housing costs rising and Lebanese landlords profiteering, unofficial makeshift camps have sprung up in northern Lebanon and in the Bekaa Valley. UNHCR has been quietly providing tents, although refugees angry with the West for what they see as a lack of aid often paint out the UNHCR logo, as a reporter for The Daily Beast witnessed when visiting a makeshift camp of 70 refugees in the village of Bar Elias in the Bekaa Valley.

Refugee Abed Razzak Khali, a 35-year-old father of two young children who fled from the suburbs of Damascus, said he cannot understand why his family is not getting more assistance. He gestured toward his 1-year-old daughter playing on her mother’s knee. “When it comes to me I can be patient," he said. "I can wait. But this girl cannot wait for food. OK, they bring us something, but what we need is much more. It is very hard."

Lebanese families that once were charitable toward the Syrians are markedly losing patience, fatigued by the refugees’ prolonged presence and resentful of the fact that they represent competition for local jobs and drain local coffers. In Shia areas the arrival of Syrian Sunnis is greeted with unease. “We are going to start seeing violence soon between host communities and refugees,” predicts the head of mission here of a foreign-aid charity.

Many aid workers are critical of the U.N.’s past failure to confront the Lebanese government over the camps issue, saying that the dispersal of refugee families with many led by widows and grandmothers has made them more vulnerable, and has stretched the logistics of relief charities as well as of the U.N.

“On the record I will tell you the no-camps approach was the right one, and it is true camps can be awful and they are demoralizing and I don’t like advocating for them,” says a veteran aid worker. “However, if you don’t have camps you then have to talk about increased resources to help the targeting of refugees, and the support of them and ensuring a balance is kept between what refugees are receiving and giving to poor local communities to ensure they don’t feel discriminated against and turn resentful.”

The aid worker added: “The U.N. should have established camps two years ago—it never had the funding to deal with a huge dispersed refugee population. It got it wrong.”

Earlier this month, Lebanese President Michel Sleiman argued that refugee camps should be set up inside Syria under the protection of the U.N., and Lebanese ministers hinted they might bar more refugees from entering the country. The Lebanese government estimates there are 1 million refugees in the country already, a figure most foreign-aid officials accept as accurate, although the UNHCR has so far registered half a million.

Sleiman’s proposal of refugee camps inside Syria could only work if the camps were adequately protected, and that would likely require Western allies putting boots on the ground and enforcing no-fly zones—unlikely at this stage, especially with President Assad now on the offensive. Government ministers have recently complained that Syrians should be shifted to outside the country because “all of Lebanon has become a camp for foreigners.”

Last month, Hezbollah’s deputy leader, Sheikh Naim Qassem, reacted sharply to a report from the influential Brussels-based International Crisis Group urging the opening of camps because Lebanon was reaching a breaking point and the dispersal of Syrian refugees is “fueling pre-existing political, social, and communal tensions.”

The Sheikh said that camps would pose a threat to Lebanon. “We cannot accept refugee camps for Syrians in Lebanon because any camp will become a military pocket that will be used as a launch pad against Syria and then against Lebanon,” he said at a conference in Hezbollah’s southern suburbs of Beirut.

But analysts here believe the biggest long-term fear for Hezbollah is that camps would shift Lebanese demographics. Judging by the estimated 400,000 Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon, some who fled Palestine at the establishment of Israel, camps would likely result in many Syrian Sunni refugees remaining in Lebanon even after the civil war is over—especially if Assad hangs on to power. Shiites would then become significantly out-numbered by Sunnis in a political system that is based on a delicate sectarian system introduced in 1990—at the end of a savage 15-year-long civil war—which allocates guaranteed government roles to the major sects.