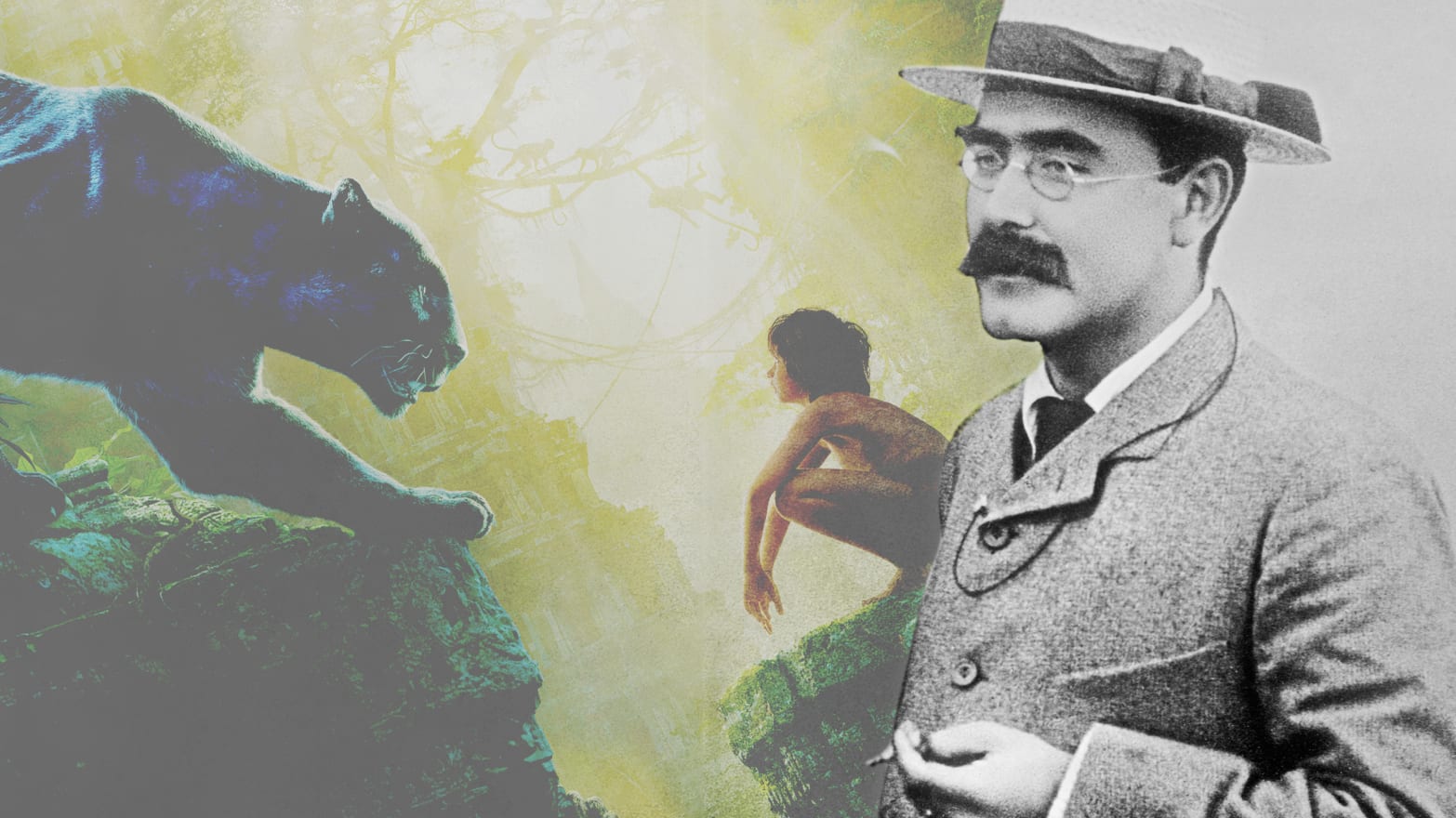

During his lifetime, Rudyard Kipling seemed like a man who could do no wrong. Like his contemporary Mark Twain, he possessed the enviable ability to appeal to both children and adults. Critics loved him, too, and so did his fellow writers. Henry James said, “Kipling strikes me personally as the most complete man of genius (as distinct from fine intelligence) that I have ever known.” In 1907, at the age of 41, he won the Nobel Prize for literature.

Kipling, though, made one big mistake. He was an unabashed fan of colonialism, and that enthusiasm put him on the wrong side of history and tarnished his reputation beyond repair. Today he is known as the man who coined the phrase “the white man’s burden,” and that, sadly, is all most people know of him.

He is back in the news now only because a movie made from his stories in The Jungle Book is posting such huge profits that Disney has already announced plans for a sequel. And yet, even here, inspired by a movie and a book that has nothing to do with colonialism or the superiority of Anglo-Saxon civilization, Kipling has again suffered the sort of ritual beating usually reserved for disgraced dictators and unapologetic eugenecists.

One recent story online bore the headline “Rudyard Kipling Was a Racist Fuck and The Jungle Book is Imperialist Garbage.” Another, slightly less virulent story was entitled “How Disney’s New Jungle Book Subverts the Gross Colonialism of Rudyard Kipling.”

This has been going on for a long time. In 1942, George Orwell called out Kipling as a “prophet of British imperialism.” If anything, that’s too tame a tag. Huckster, pitchman, shill—all better descriptions. Because there is no denying that Kipling wrapped himself in the Union Jack and sold the idea of a British empire as hard as he could for as long as he could.

But even Orwell refused to condemn Kipling outright, first because Orwell hated the pious liberals who hated Kipling more than he hated Kipling, but second because he grudgingly admired Kipling. Indeed, he goes so far in his Kipling essay as to ardently defend Kipling against those who accused him of being a fascist. He was an imperialist who truly believed that English values would civilize the world. But that did not make him a fascist. It just meant that he was, if anything, a sort of deluded idealist—misguided and too often shortsighted (Orwell again: Kipling never understood the money end of colonialism, never saw that it was a system not merely of superciliously “civilizing” people but of ripping them off as well), but an idealist all the same.

None of this would matter, to Orwell or anyone else, if Kipling had not been a great writer. There is good reason—beyond the fact that it’s in the public domain—why Hollywood has tackled The Jungle Book stories no less than three times. The stories of Mowgli and his animal brothers are enchanting (and the Mowgli stories account for only about half of The Jungle Book). They read not like stories that someone made up but like fables handed down through the generations. They never try to do too much—they certainly never strain for any high-minded moral—but they are utterly satisfying, even on repeated encounters, as any adult who has read them aloud to a child can attest.

Certain critics, however, typified by those who posted the screeds mentioned above, have no patience with complication. In their accounting, the bad in Kipling always outweighs the good, and in The Jungle Book or Kim, they are content to see nothing but tales of colonialism, racism, and a love of power for its own sake.

You don’t need to be a Kipling zealot to see how far short this condemnation falls of any true assessment. You only need to read the stories themselves to see that they do not support such analysis.

It is worth noting here that readers in India and Pakistan share few of the reservations Westerners harbor regarding the poster boy of colonialism. He is often even taught in schools in those countries.

The Jungle Book stories were not written by Colonel Blimp. They are not propaganda. They have no agenda. And they are not, in fact, even very optimistic at heart. If anything, Kipling’s tales quietly but inescapably leave their readers with a chilly view of life—nasty, poor, brutish, and short (except for elephants, who live practically forever). First and last, the Mowgli stories condemn all humans as foolish, superstitious, mean-spirited, and full of hubris, specifically for our propensity to assume superiority over the animal kingdom.

Animals, excepting monkeys, elicit Kipling’s respect. Humans, certainly adult humans, rarely do. The family in “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi,” the only whites to appear in the stories, are helpless twits who, were it not for the eponymous mongoose, would’ve all been murdered by cobras. And yes, Mowgli has the ability to stare down almost every animal he meets, but as his teachers Baloo the bear and Bagheera the leopard constantly remind him, that is not much of a talent given that he has so much else to learn from animals and a long way to go before he’s learned it.

The saddest part of the Mowgli stories, though the author doesn’t trumpet it, is that Mowgli is a boy with no culture of his own. He knows he can’t run with the wolf pack that raised him, and his human kin expel him from their village and threaten to kill him (I’d be willing to bet that Kipling spends more time skewering human stupidity than almost any other author—he was obsessed with it.)

But great as it is—and certainly redder in tooth and claw than the usual children’s book—The Jungle Book is nonetheless still a children’s book. It shows only one or two facets of Kipling’s genius. To truly appreciate how great he was, you must read the short stories, which are not only wonderful tales (“The Man Who Would Be King,” “The Strange Ride of Morrowbie Jukes”) but just as often brilliant psychological studies that Chekhov might have envied. To cite but one example: it takes a special kind of genius to successfully invade the mind of a child—Henry James and Faulkner could it, and Jean Stafford, too, and so could Kipling. “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep,” the vaguely autobiographical story of an English brother and sister sent home from India to live with an aunt, is one of the most claustrophobic, heartwrenching stories I know, and all its power derives from the fact that it never leaves the little boy’s head: the entire reality of the story, complete with childish misunderstanding, is his, and if any story ever delivered the reader straight back to those horrors of childhood that we’ve spent a lifetime repressing, it’s this one.

None of this will matter, though, to those who never pass up an opportunity to happily dismiss Kipling as a jingoistic fool who wrote a lot of bad poetry. They’ll just keep telling us how awful he is. Perhaps they take some grim satisfaction in feeling superior to those in the past who made bad choices when it came to politics and world affairs. Perhaps they can’t see that judging people in history by modern standards is a useless pastime.

The truth is, Kipling wrote a lot of ill-conceived garbage and he wrote a lot of truly wonderful fiction as well, and it’s usually not at all hard to tell the difference. Even when it is, the effort is justified. Pondering how a writer so good could occasionally go so wrong forces us to contemplate how all of us, even the most enlightened, can be swayed and deluded by the assumptions and beliefs that hold sway in the times in which we live. But doing that requires that we understand that in Kipling’s shoes, we might have made the same mistakes. And what fun is that? Certainly not as much fun as digging him up every generation or so and beating him like a piñata.