It sounds like an oxymoron: high-tech fertility treatments for poor women in impoverished countries. Others call it just plain moronic.

The whole idea, bringing in vitro fertilization to places such as sub-Saharan Africa, is polarizing public-health experts, with one faction saying all women deserve access to every kind of reproductive health and the rest pointing to other pressing diseases that trump fertility when it comes to parsing out limited resources in the developed world.

“It’s so contentious,” says Marcia Inhorn, a Yale anthropologist who has written extensively about global infertility issues. Her latest book is The New Arab Man: Emergent Masculinities, Technologies and Islam in the Middle East. She fervently believes that “people should have access to technologies and things that will give them reproductive freedom and choice.”

Jennifer Kyarompa, a 36-year-old nurse in Kampala, Uganda, who works at the Joyce Fertility Center there, echoes the sentiment. All too often, infertile women are considered cursed, she said. Their husbands abandon them and “they go back to their parents and everyone is talking this and that whenever they pass.” She knows it’s nonsense, but it’s hard to convince folks otherwise.

Paradoxically, sub-Saharan Africa has the world’s highest rates of both infertility and fertility. Roughly one-in-four women suffers from infertility. At the same time, Africa ranked highest in fertility rates, according to a United Nations report (PDF), released in June 2013. Some 29 of 31 high-fertility countries are in Africa, the report found. That means that while many women in Africa can’t have children at all, those who can are having lots of babies. The overall population growth in Africa—expected to double by 2050—masks an epidemic of infertility.

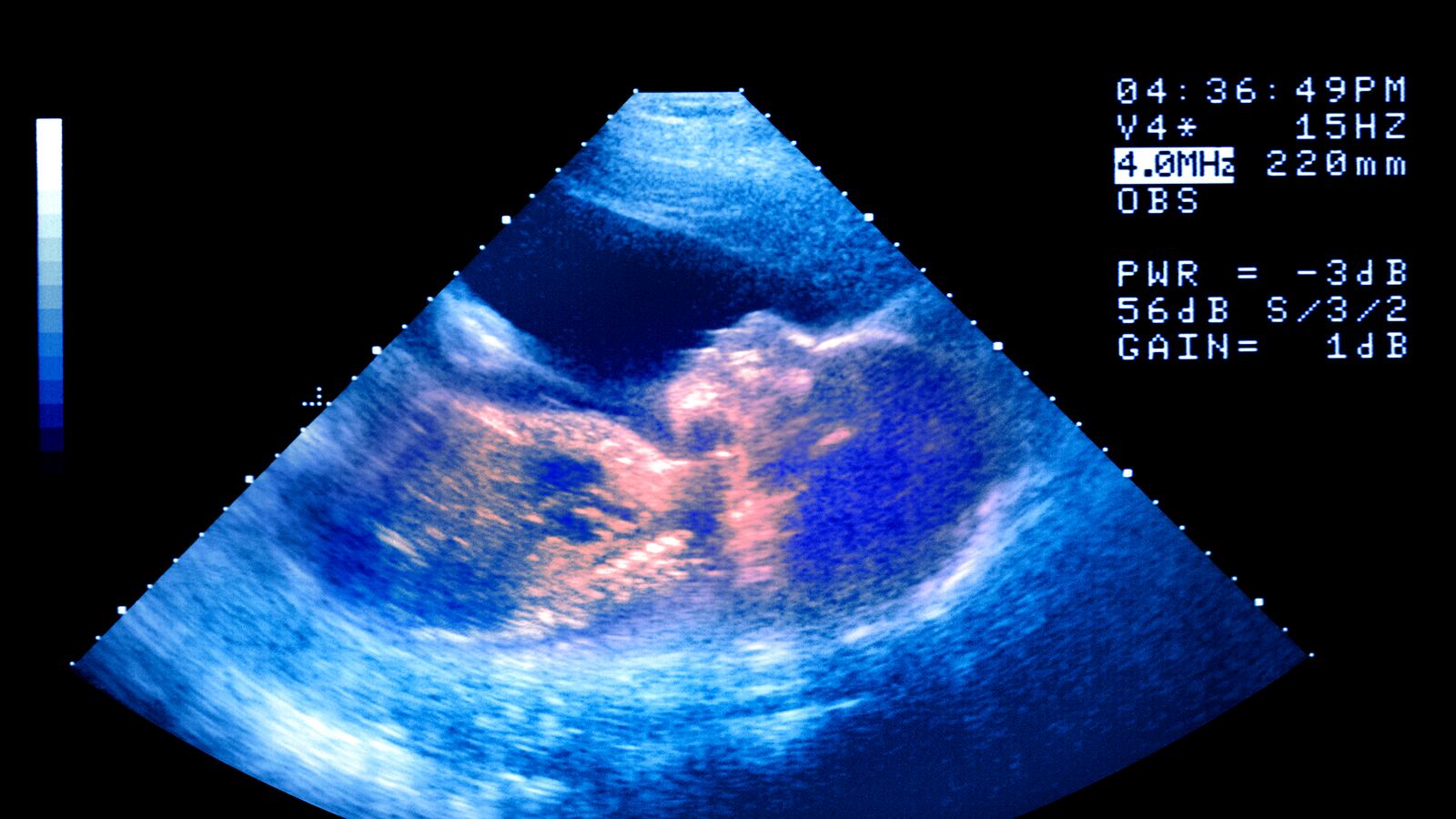

The vast majority of infertile African women can’t get pregnant because of fallopian tubes clogged by infections. That makes them, in one sense, perfect candidates for in vitro fertilization because IVF works best on women who have clogged tubes and no other hormonal issues. Doctors bypass the tubes and place the embryo right in the womb. Skeptics point out that money should be used to prevent infections in the first place.

All of these issues came to a head this summer in London at a European fertility meeting where Dr. Willem Ombelet, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Institute for Fertility Technology in Genk, Belgium, presented the results of his latest study testing his low-cost system. He says it can be done in a lab about the size of a walk-in closet using “kitchen cupboard” ingredients. He keeps the embryos alive without fancy culture media but rather a sort of “Alka Seltzer” solution (citric acid mixed with sodium bicarbonate). In his experiment in Belgium, he gave fertility drugs to female volunteers, 36 years or younger. Among those who spewed at least eight eggs, half would be fertilized with the new, cheaper technique and the rest with the old-fashioned expensive way. Fertilization rates and implantation rates were similar—about 35 percent.

So far, 12 babies have been born with the cheaper method. Ombelet’s also treatment, even at its cheapest, is still about $300 a cycle, much lower than the thousands of dollars it costs for treatment in the West, but still a high price tag for the impoverished. He aims to test his low-cost system in Africa next spring. It remains to be seen whether the technique that seemed to work well in a lab in Belgium will yield similar results in a clinic in Africa.

As in all things medical, his foundation, The Walking Egg, isn’t the only one. Already there is competition from other teams, one based in the United States, called Friends of Low Cost IVF.

And yet, despite the banter, the crux of the issue is the feasibility of it all. Can scientists, as some claim, really offer high-quality in vitro fertilization in makeshift clinics and at bargain-basement prices?

The notion of sparing a woman a life of destitution is a noble one, not to mention there is an inherent fairness in offering them treatments that are available to wealthier women elsewhere. But in order to make it work, what’s really needed is a full-fledged maternal-health structure: one that provides preventive medicine to avoid the infections that cause infertility in the first place; contraception for women who want to limit their families; and primary-care services for pregnant women and their newborns. Perhaps this one addition of low-cost fertility is one step to spur a larger health effort. Otherwise, it’s just a piece of technology without a support system.