Imagine riding through space on your trusty scooter and, feeling the urge to lasso an asteroid, reaching out and doing just that. It is a top-notch, boyhood sci-fi fantasy. If the scooter were pink I would ride it, too.

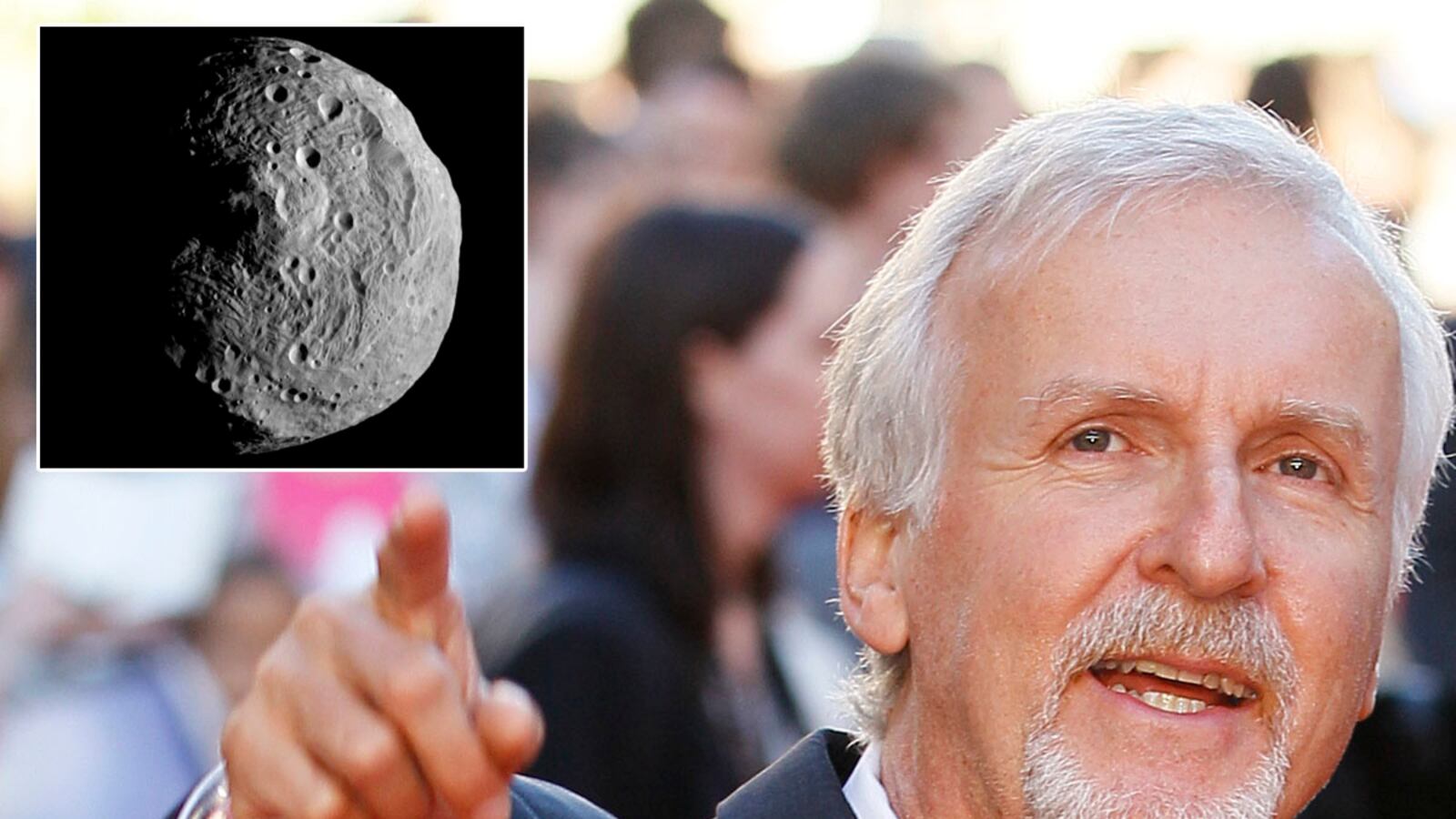

After his journey to the icy-dark ocean depths, film director James Cameron is heading to space. He is advising a company called Planetary Resources, details of which will be unveiled today. The press release announces the stealthy company’s mission is to “overlap” space exploration and natural resources with a plan that will “add trillions of dollars to the global GDP,” and “help ensure humanity’s prosperity.” (Company webcast, April 24, 10.30 PDT, Twitter: @PlanetaryRsrcs)

It is not yet clear if Cameron will once again explore alone or if he will be accompanied by another cowboy. It is not exactly a joy ride, because the lasso means business—commercial space exploration business. The plan is to mine asteroids to be used on Earth and for interplanetary travel.

Planetary Resources is backed by Google cofounder Larry Page; Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt; Peter Diamandis, who funds the entrepreneurial X Prize; Eric Anderson, a former NASA Mars missions manager; Ram Shiram, a Google director and venture capitalist; former Microsoft executive Charles Simonyi; and Ross Perot Jr., son of the tech businessman and onetime presidential candidate, Ross Perot.

Back in 2005 in his TED talk, Diamandis raved about asteroid mining since the Earth is “a crumb” and space is a “supermarket filled with resources.”

Asteroids have bounty to offer; so much so that “current views of ‘limited resources’ must be rethought,” says John Lewis, professor emeritus at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. An adviser to Planetary Resources, he lauded the possibilities of asteroid mining in his 1997 book, Mining the Sky, Untold Riches From the Asteroids.

At first glance, the company’s wackiness factor seems high. “In principle it makes sense, but it’s a long-term project for sure,” says Esther Dyson, herself an avid space entrepreneur.

The Wall Street Journal wrote that Planetary Resources seeks to convince governments to lasso an asteroid into lunar orbit, so companies can vie for mining contracts. The Journal later corrected the story, stating that the plan involved sending an unmanned space vehicle to an asteroid to do mining.

The details on how to lasso an asteroid are still being worked out. Earlier this month, the Keck Institute for Space Studies (KISS) at California Institute of Technology/NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., published a study authored by a team of space scientists from across the country about the technology and know-how needed to identify, robotically capture, and haul in an asteroid that is about 22 feet across (seven meters) and weighs about 550 pounds (500 metric tons) and bring it closer to Earth for mining purposes.

The asteroid-capture-and-return-mission concept, according to the report, “fits well” with the current human space-flight goals of NASA and its international partners. Retrieving an asteroid for human exploration and exploitation “would provide a new rationale for global achievement and inspiration.”

As the KISS report outlines, a 500-ton asteroid can contain more than 100 tons of water and more than 100 tons of carbon-rich compounds, 90 tons of metals (iron, nickel, and cobalt), and 200 tons of silicate, which is similar to the surface of the moon.

“The resources available in the near-Earth asteroids are far greater than Earth’s surface provides,” Lewis says. And the asteroid belt contains another factor of 1 million times as many raw materials.

If you had infrared vision and could spend a year taking pictures of the night sky, you could catalog as NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) did: half a billion stars and galaxies and near-Earth asteroids. The catalog, made public last month, shows that NASA has already found more than 90 percent of the largest near-Earth asteroids. In that sense, there is a map ready to go for Planetary Resources and any other commercial space business keen on mining asteroids.

“I’d really love to see a spacecraft launched to rapidly discover NEOs [near-Earth objects]," says Timothy Spahr, a researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. The race to discover these objects is “headed to space for sure.”

Lewis says it was Konstantin Tsiokovsky who first pondered “exploitation of asteroids” in 1903. Tsiokovsky probably would be thrilled about Planetary Resources.

Lewis explains that he and Princeton physicist Gerald O’Neill made asteroid mining a central theme of the annual Princeton Space Development Conference series in the 1970s. Planetary Resources may well be his boyhood dream come true.

Mining asteroids is about iron and nickel as well as cobalt and platinum-group metals, but also water and energy, he says. While the platinum-group metals and the energy harvest would be for Earthly uses, “the rest are for use in space,” he says, for example, for large space structures, habitats, solar-powered satellites, life-support systems, and propellants “for moving the mass around to where we need it.”

Lewis retreats when asked about the economic viability of the proposed company, saying the billionaires backing the company are better judges of potential success. “They obviously are seeking something other than a tax write-off,” he says.

A financial analyst, who did not wish to be identified, says these ventures are going to be mighty pricey. Not only is mining asteroids hard, but mining equipment is heavy. “Launching heavy things in space is the most expensive portion of all missions,” he says. Besides not being sure if one has selected a good asteroid to mine, the mineral-extraction business “requires tons of energy and mass on the ground,” so it is hard to estimate how much the tally would run in space. “I suspect hundreds of billions of dollars,” he says.

Writing about the history of space flight, Linda Billings, a researcher at George Washington University School of Media and Public Affairs, points out that space advocacy advances the idea of outer space as “a place of wide-open places and limitless resources” which are loaded concepts that in American history conjure up ideas of pioneering, claim-staking, and taming.

As a longtime critic of the “conquest-and-exploitation approach to space exploration,” she says she is eager to see Planetary Resources’ business plan, customer commitments, financing, available launch vehicle, and space-mining equipment. “I assume, but cannot prove, that there’s no affordable way to engage in this sort of project,” she says. Until she sees their business plan, however, “I can’t say anything about viability.”

After today’s press conference, many space cowboys and cowgirls will be weighing in on the company’s prospects.