The nuclear crisis at the Fukushima reactors has set off calls to close nuclear power plants around the world. But closing reactors alone would do nothing to address what caused the real damage in Japan—the spent fuel rods that are supposed to be cooling in pools. When three of the seven pools were damaged, and in one case entirely drained, by the tsunami, the spent rods began emitting high levels of radiation.

The United States has about 100 such spent fuel pools. I visited one a few years ago at the Indian Point nuclear power plant, which sits up the Hudson River in Buchanan, New York. Indian Point is back in the news because it operates a mere 35 miles outside New York City. More than 20 million people live within a 50-mile radius of the plant. Getting out in the case of a disaster would be a nightmare.

Getting in wasn’t easy either. But after taking a course called “radiation training,” undergoing a “dose assessment” (to be measured against my readings afterward, which showed less exposure than to an X-ray) and passing a written test on how to handle myself in a confined space, I was finally allowed to enter the facility. Clad in the jumpsuit, helmet, goggles, and booties made famous by Homer Simpson, I expected to be transfixed by the fully operating core of the reactor just a few feet in front of me.

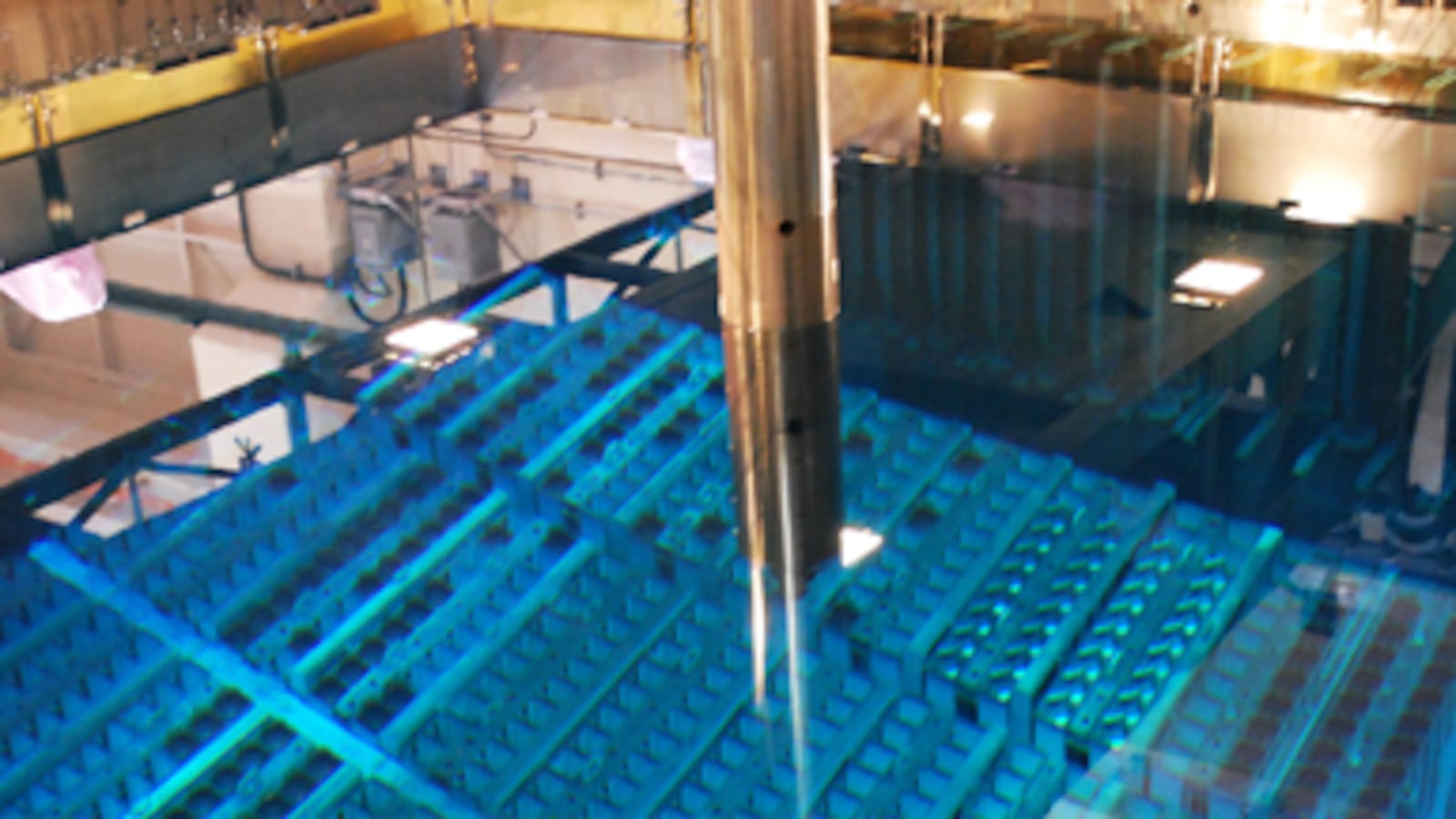

Instead it was the 38-foot-deep pools, with the spent rods lying at the bottom, that scared me. Unlike the reactor, the pools aren’t “hardened targets” protected from earthquakes or terrorists by a concrete containment dome. At least at Indian Point, the pools lie in bedrock. In the Fukushima facility, and at many American plants, they are above ground, with roofs not much thicker than those at your local swim meet.

I learned that day of a process called “dry cask storage” that seems to offer a safer alternative. In dry casking, a technology that dates to the 1980s but has only been adopted in recent years, the rods are housed outdoors in storage pads 3 feet thick and 100 feet by 200 feet wide. While this sounds promising, it turns out dry casking at Indian Point and other American nuclear power plants is a supplement to the pools, not an alternative. Only in Germany have they moved to replace the exposed pools altogether.

Dry casking at Indian Point and other American nuclear power plants is a supplement to the pools, not an alternative. Only in Germany have they moved to replace the exposed pools altogether.

At Indian Point, authorities only began dry casking in 2008 because the pools were so crowded that there wasn’t room for newly spent rods coming out of the reactor. According to Entergy, the company that owns the Indian Point plant, “reconfiguration of the spent fuel pool is not part of the dry cask storage project.” In other words, the pools won’t be drained any time soon, at least not intentionally.

And don’t imagine that Yucca Mountain, Nevada, the designated site for burying at least some spent fuel, will be housing Indian Point’s spent fuel rods in the near future. The rods have to stay in the pools or dry casks for decades before they can be safely transported anywhere.

Because nuclear power is clean, it has undergone a revival lately. President Obama and progressives concerned about climate change have endorsed building new plants. There are two reasons we shouldn’t. First, as the legendary venture capitalist Vinod Khosla told me, the government subsidy required to make nuclear power competitive is virtually identical to that of solar and other alternative sources. It’s just that the nuclear subsidy is hidden in the form of insurance guarantees enacted by Congress in the 1950s and other backdoor help.

For the second reason, look no further than Fukushima. The “design basis earthquake” model used to test the dry cask storage at Indian Point was 6 on the Richter scale. Japan’s quake? 8.9.

Jonathan Alter is a national correspondent for Newsweek and a columnist for The Daily Beast. His bestselling book, The Promise: President Obama, Year One, is out in paperback with a new epilogue covering 2010.