Six hundred feet south of Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago, the billionaire Jeff Greene presides over a fiefdom of his own. An army of landscapers lines his driveway, which meanders past a tennis court, a guest house, and a pool before reaching a white stucco colossus: his residence. There are so many doors inside of the courtyard it’s hard to decide where to knock.

The morning I visit, a green door eventually swings open, and the real estate tycoon waves me into the backyard while he finishes a call. A vast lawn, appointed with a jungle gym and bronze mermaid, peers out over the Atlantic. His goldendoodle, Cole, promptly pees on my foot.

Sixty-seven years old and with three young boys, Greene is feeling uneasy about the future. Ensconced in Palm Beach—a literal island of mega-wealth—he sees an economy on the brink.

When the bottom falls out, Greene predicts, extreme “social unrest” may follow, as construction workers, cooks, housekeepers, and mortgage brokers are laid off. “Do I think that a catastrophic recession [could] really cause a lot of havoc in people's lives, could lead them to riot, get desperate?” the billionaire asks himself. “Absolutely.”

Greene insists he isn’t panicking. His bank account has plenty of cushion, and he doesn’t plan to flee the country. “I'm not worried about it in the sense where I think, ‘Am I going to be safe?’” he says, of blowback against the rich. “I’m not like, you know, out building a bunker.”

But more than once, he mentions a former belief that used to bring him comfort: “We always thought in Palm Beach, if there's ever a problem, they'll raise the bridges”—insulating the island from outsiders.

Two years ago, when demonstrators marched toward Palm Beach after the murder of George Floyd, Greene sat nervously in his mansion. “They didn't raise the bridges,” he recalls. “Apparently, the police don't control the bridges. It's controlled by, like, some maritime authority, and they said they don't have the authority to do it. So hundreds of people came across the bridge…They were coming towards our house.” (Demonstrations in the area were largely peaceful, according to the local press; Greene later clarified that those marching had legitimate reason to protest.)

His suggestion to avert more unrest? Greene—who ran for the U.S. Senate and Florida governorship as a Democrat in 2010 and 2018, respectively, losing both primaries—serves up a buffet of progressive talking points: more immigration, not too many cops, making sure people can heat their homes and pay their electric bills, finally addressing rampant inequality.

“When I was a kid growing up,” he recounts wistfully, the income gap wasn’t so stark. “The really rich people had a Cadillac or a Lincoln Continental instead of a Chevrolet or an Oldsmobile or a Dodge. They had a house on a street, maybe [in] the rolling hills, and a two-car garage and a big backyard. Nobody lived in homes like I live in today.”

It’s a surprising sentiment coming from a man who says, of keeping his family grounded, “We have some staff, but we try not to overdo it.”

Greene—worth an estimated $7.2 billion—wasn’t always this rich, however. His parents lost everything in the late 1960s, when his father’s textile machinery business collapsed, forcing his mother to start waiting tables. He says he worked three jobs to make his way through Johns Hopkins. Now, positioned near the apex of American capitalism, he has sincere concerns about the future.

The question is whether anyone wants to listen to the guy in the $97 million house.

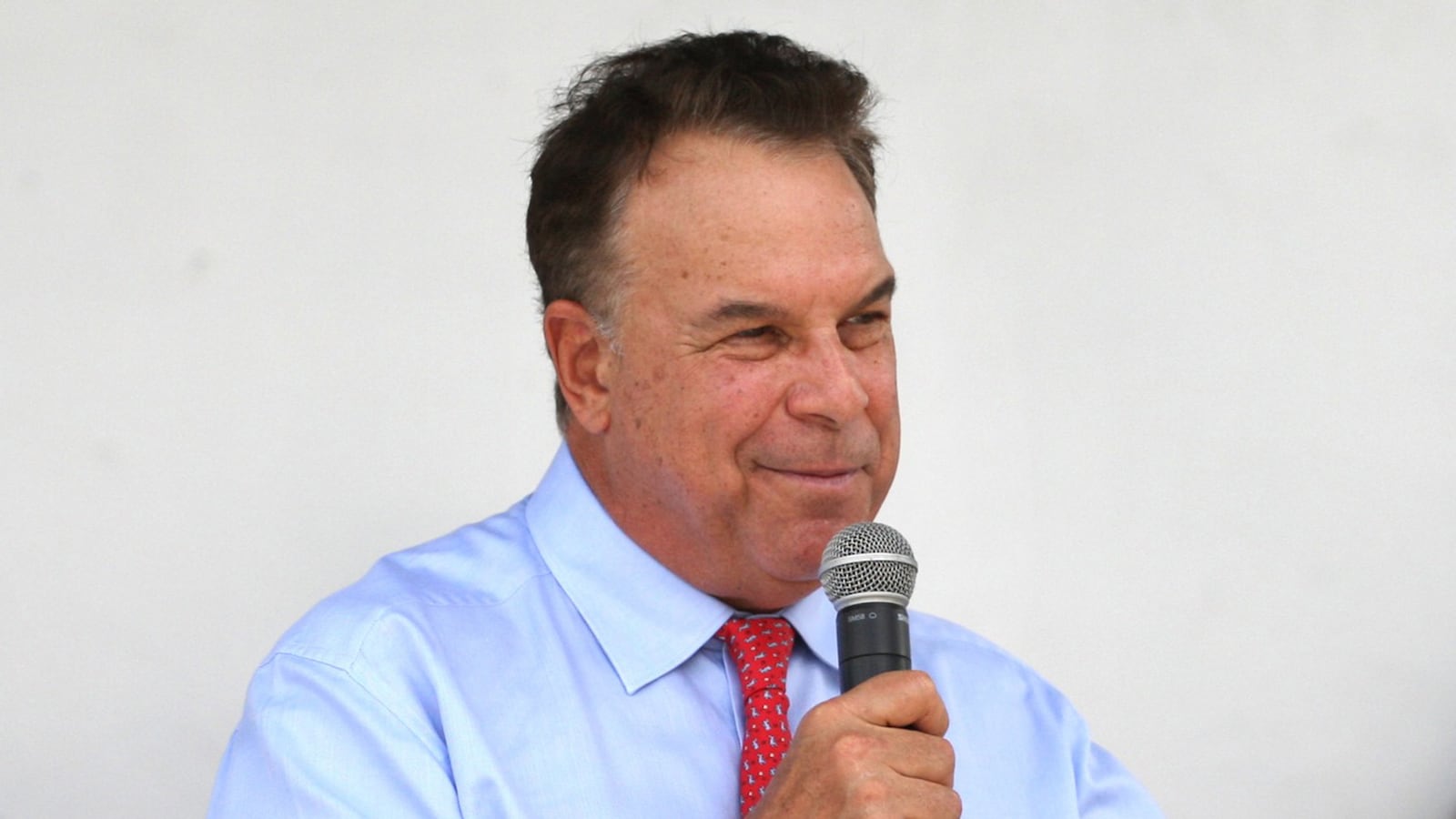

Jeff Greene mingles after speaking at Florida League of Cities gubernatorial candidates forum in Hollywood, Florida, in 2018.

Joe Skipper/ReutersIt’s not easy to fill 40,000 square feet, so it helps that Greene has a taste for fine art. He commences a tour of the ground floor, one cavernous room after the next. There are paintings by Francis Picabia and Monet, and contemporary artists Dominique Fung and Christina Quarles. A massive mobile he bought at Art Basel dangles in the piano room, and there are three sculptures by Aristide Maillol formerly owned by John Kluge, who was once the richest man in America.

“He lives with the collection,” says Jeffrey Deitch, an art dealer and adviser who has known Greene for more than a decade. “There are a number of collectors today where most of the works are in storage. That’s not the case at all with Jeff.”

The tour continues: past a photo of George W. Bush kissing Greene’s cheek, into the movie theater, where roughly a dozen plush couches face the screen and candy dispensers fill an entire wall. Greene eyes the dispensers looking mildly disappointed; some of them are empty. “There’s usually more,” he shrugs.

It’s a lot of stuff, almost a caricature of affluence, though to Greene’s credit, he amassed his fortune from scratch. His grandfather immigrated penniless from Lithuania before founding the textile machinery business Greene’s father later took over. Greene used to accompany his dad on work trips as a kid in Worcester, Massachusetts.

After Johns Hopkins, Greene spent close to three years as a circus promoter (he hated it), then found his way to Harvard Business School in 1977. There, he entered the real estate business, buying a three-family home in Somerville, Massachusetts; he lived in one unit and rented out the others. By the time he graduated, he says, he had acquired 18 properties. He spent decades expanding the portfolio.

Counterintuitively, it was during the Great Recession that Greene finally cracked the Forbes billionaires list. He bet against bonds underpinned by crappy subprime mortgages, reportedly earning an $800 million windfall when the housing market collapsed.

Since then, he has continued to build: a 300,000-square-foot warehouse complex, 72 New York City condo units, a pair of towers in West Palm Beach—attracting bursts of controversy along the way over contract disputes and gentrification complaints. Last year, some West Palm Beach residents publicly derided high-rises he wanted to construct.

I ask Greene what he thinks of rising anti-billionaire sentiment. “There’s a lot of pent-up anger, and existing anger, and jealousy towards uber-wealthy people,” he says. “Most people, you know, just make ends meet.”

He tries to stay normal, he tells me, by driving his kids to and from school, and having dinner each night as a family.

He relays another anecdote in an effort to bolster this point. In the Hamptons, where he’s building an extravagant residence on his 55-acre estate, his boys have spent the past two summers sharing a room in a relatively modest home on the property (though still bigger than the houses Greene grew up in).

“A lot of people would have said, ‘Oh my God, I better go rent a big mansion because that’s the only thing I can live in now at this point in my life,’ and we didn’t,” he says.

Greene says that he won’t leave the kids “crazy amounts” of wealth, lest they lack work ethic and ambition; he wouldn’t want money to change them.

Jeff Greene, then a candidate for U.S. Senate, announces his concession to primary opponent Kendrick Meek.

Joe Skipper/ReutersGreene lounges on a couch in his office, surrounded by mock-ups of his grandest projects. Beside him, on TV, economic data dances across the screen: markets are shaky, inflation is stubborn, Britain’s leadership seems drunk—none of it looks good.

He has strong opinions about America’s trajectory, and he’s in the mood to share. He singles out Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chair, whom he seems to view as a blithering idiot.

Greene blasts the Fed for dilly-dallying while the market was growing too hot. “Clearly, [there was] just too much cash floating around,” he says—people were plowing their savings into cryptocurrencies and new homes.

Excess demand begot inflation, Greene continues, and Powell failed to punctually respond; when the Fed finally did take notice, it overcompensated.

“I get [that] you take away the punch bowl from the party because you don't want people to drink anymore,” Greene says, referring to raising interest rates to cool inflation. But he thinks the increases were way too aggressive: “You don't have to also push them down two flights of stairs on the way out and kill them.” (Fellow Palm Beach billionaire Ken Griffin, meanwhile, has endorsed the rate hikes, and Powell previously received wide praise for his stewardship of the Fed at the height of the pandemic.)

Greene asserts that Powell doesn’t comprehend the medium-term impact of raising rates. Greene’s buildings, for example, are already under construction; otherwise, he wouldn’t be building. When the current projects are finished, he says, activity will grind to a halt.

At that point, maybe in another six or nine months, he forecasts, the economic toll will finally be visible. Hotel traffic will slow, construction workers will lose overtime, and restaurants will cut pay. And, in his mind, cue the social unrest.

Over the longer term, inequality will pour gas on the anger, Greene says. He thinks “the biggest danger” would be a “socialist-type” government that raises taxes and scares off entrepreneurs.

I ask Greene how he would fix things. He pauses. “Well, that’s a whole other long story.”

The answer comes a moment later: “The great equalizer”—education.

“All you can do as a society,” he declares, “is get everyone to the same starting line.” And as it turns out, Greene is working hard on this issue—albeit with arguably the fanciest school in all of Palm Beach County.

Jeff Greene with investment banker Mary Erdoes at Davos in 2015.

Phil Wenger/Phil Wenger/Wikimedia CommonsSituated in an old Mazda dealership, The Greene School—named for its billionaire benefactor—offers an education befitting the elite. Students learn dance and mindfulness, tinker with 3D printers and flight simulators, and perform musicals at the Kravis Center in downtown West Palm Beach. Enrollment is highly competitive, with mandatory IQ tests and a two-day trial to evaluate compassion and politeness. The tennis instructor, Alex Bogolomov Jr., was once ranked 33rd in the world.

Greene strolls into the cafeteria. Panes of glass stretch from wall to wall, bathing the room in natural light. The students look happy; it’s cheeseburger day. Their patron is looking buoyant, too.

“At this point in my life, I love making money, I love doing deals. But honestly, the biggest kick I get is from making a difference in other people's lives,” he says. Historically, he adds, his assets have been parked in real estate, denying him the liquidity to give away more.

Greene and his wife of 15 years, Mei Sze Greene, founded the school in 2016, six years after signing the Giving Pledge—a non-binding agreement to donate at least half of their wealth—and after finding their eldest son’s education unsatisfactory. “Nothing against that [former] school,” Greene says, but “people would just be whining non-stop about how frustrated they were.”

The Greene School launched with 42 kids from pre-K to fourth grade. Today it runs through ninth grade and has 186 students, roughly half of whom are on financial aid. Greene pours about $2 million into the operation each year, and his children (ages 9, 11, and 13) all attend.

“I love working with him, it’s a lot of fun,” says head of school Denise Spirou, who praised Greene for giving her administrative autonomy. “It’s like a roller-coaster ride, sometimes it can be, you know, expect the unknown, and sometimes it’s exhilarating.”

The school, which charges between $25,000 and $35,000 per year in tuition, is clearly a passion project. Greene reads a letter from a retired Wall Street bigshot praising the “incredible education” there. “You have many, many accomplishments, but building such a beautiful school from scratch has got to be near the top of the list,” it says.

Greene reflects on this. “I’ve accumulated all this wealth, and now I can go out, and I get to be a hero in this guy’s eyes,” he says. “It’s more fun to be able to give than to receive.”

We exit the school. In the distance, cranes tend to One West Palm, a pair of 30-story towers Greene hopes to complete next year. Construction hit a snag in 2020, after he pressured city officials for a zoning change. When they initially refused, he threatened to walk away entirely. “I'll leave the shell up. It's going to look like a skeleton,” he told The Palm Beach Post. But in the end, he opted for peace.

It’s the night of Halloween, and the Greene estate is buzzing, featuring a high-volume commotion about adding onions to the dinner menu. Through the din, the billionaire picks up the phone to ruminate one last time on his legacy.

“I have [only] so many good years when I can really be active and run around and do stuff,” the former late-night party fixture says.

The challenge is how to fill them. Greene has mostly given up on higher office, acknowledging that getting elected “just isn’t something I’ve obviously done very well at.” Nor does he want to bring The Greene School to other cities. He’ll disburse more cash to educational and Jewish causes, but mostly, he seems eager to rest.

“I’m working way too much,” he says. When the West Palm Beach towers are finally done, he’ll have more time to spend at his mansion. Already once expanded, he has plans to extend it once more.

“My life’s just a fairytale, from where I came to where I am now,” Greene says. “I wake up every day and I’m so grateful.”

He hangs up swiftly. The kids want to go trick-or-treating, and they can’t just walk out the front door, since the neighboring properties are way too big. “If we went here, they’d only get to go to three or four houses in one night,” Greene says.

Instead, they’ll drive to the island’s north end, where the streets will be cleared and the “still beautiful” homes are closer together. Though if the kids from West Palm Beach want to join the fun, they better hope no one raises the bridges.