A young man, still a student, has seen the rise of authoritarian states to heights of frightening power. He writes, "When it competes with a system of government which cares nothing for permanency, a system built primarily for war, democracy, which is built primarily for peace, is at a disadvantage."

Twenty years later, preparing to seek his country's highest office, the young man's observation is unchanged: "A free society," he says, "is at a disadvantage in competing against an organized, monolithic state."

These are interesting thoughts, though debatable to be sure. But they are self-evidently not the observations of someone of our own time, someone who has seen communism fall and democracy triumph across most of the planet, who has seen the emerging challenge of nonstate actors, who has seen American power remain predominant for three generations and counting.

Kennedy speaks to us still about how "the energy, the faith, the devotion" that are brought to public service can "light our country and all who serve it."

They are the thoughts of John F. Kennedy—and not casual ones either. The first quote is from the book Kennedy published in 1940 based on his senior thesis at Harvard, Why England Slept. The second is from an interview he gave during his 1960 presidential campaign.

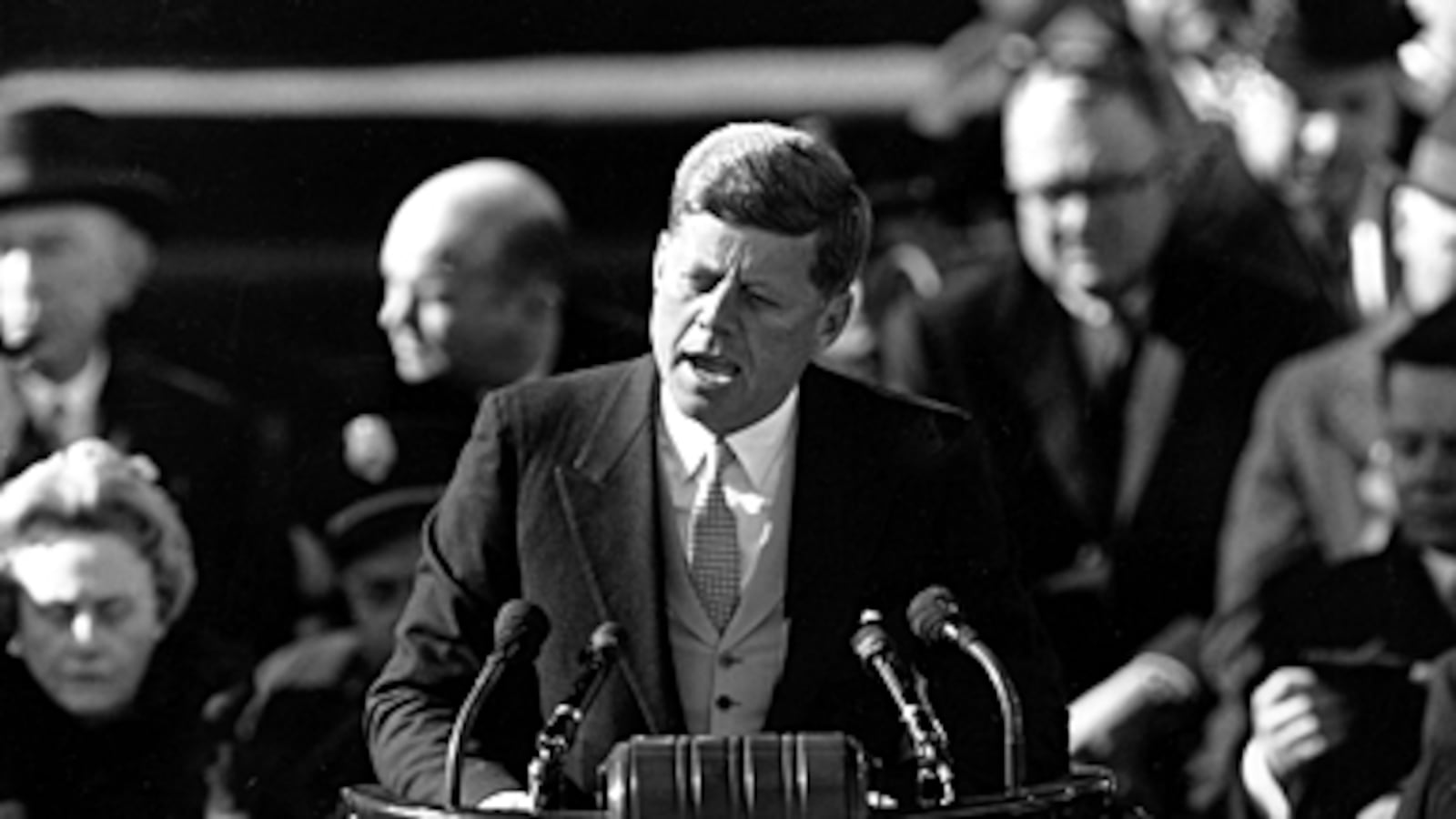

It is 50 years today since Kennedy became president, since he asked us to "ask not." In many quarters the event will be recorded as a nearly contemporary one, as one of the dawning moments of our own age, surely as the first speech to truly seize the power of television. But in fact the Kennedy inaugural, if we honestly revisit its substance, is a relic of an age gone by.

First, the address deals almost entirely with the global struggle with the Soviet Union, then in midcourse. It assumes for the speaker's generation the role of "defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger." It was to the Soviets, above all, that Kennedy was speaking when he declared America's Cold War commitment to "pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to assure the survival and success of liberty."

He did so because he deeply believed that the office he was entering held the best hope of making up for the "disadvantage" of democracy. In that 1960 interview he had noted that in facing the Soviets, "we prize our individualism, and rightly so, but we need a cohesive force. In America, that force is the presidency."

More broadly, Kennedy's inaugural was devoted almost entirely to foreign affairs, not just because he saw international challenges as paramount but also because he had a view that something approaching an "end of history" had occurred in our domestic debates. He and Republican Richard Nixon had disagreed on a few such questions in the campaign just past, but Kennedy and those around him were inclined to see such points as tactical and transitory. Civil rights at home were the subject of a two-word aside inserted in the speech at the last moment.

Like all "end of history" mindsets, this one proved premature, and domestic issues increasingly divided Americans during the Kennedy years and thereafter. This should come as no surprise, simply because of the passage of time. The 1961 inaugural is more distant from our own era than the beginning of the First World War was from Kennedy's time, or than the onset of that global conflict was from the end of the Civil War. In other words, it was long ago.

Kennedy's generation is passing. Theodore Sorensen, the principal author of the inaugural speech, died in October. Kennedy himself, forever young in our memory, would be 93 if he were alive today. Four of Joe and Rose Kennedy's nine children died suddenly and young. But four others have now died of natural causes and at advanced ages; only Jean Kennedy Smith, soon to be 83, survives.

President Kennedy was the first of the Second World War's junior officers to come to power, "tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace," as he defined them in the inaugural. The transition was especially poignant because he succeeded the war's most celebrated senior officer, Dwight Eisenhower. But the last of the junior officers to serve in the presidency, the first George Bush—just seven years younger than Kennedy—left Washington nearly 20 years ago. Bush's son has now retired, and his successor, Barack Obama, was not yet born when Kennedy delivered his inaugural address.

Why, then, mark today's anniversary at all? The answer can be found in the power of the rhetoric itself, in Kennedy's call to service, and in the respect reflected in the high plane on which he addressed his fellow citizens.

This is always the way it is when great speeches pass from their historical moment into the timelessness of historical regard. We value the Gettysburg Address not merely to honor those who gave the "last full measure of devotion" on the battlefield but for Lincoln's vision of government "of the people, by the people, for the people." We should honor John Fitzgerald Kennedy not so much for what he said to the audience before him 50 years ago but for speaking to us still about how "the energy, the faith, the devotion" that are brought to public service can "light our country and all who serve it—and the glow from that fire can truly light the world."

Richard J. Tofel is the author of Sounding the Trumpet: The Making of John Kennedy's Inaugural Address and the forthcoming Eight Weeks in Washington, 1861: Abraham Lincoln and the Hazards of Transition.