LONDON — He was dying in a bedroom on the first floor of a three-story attached brick house that has a tangle of black drainpipes running down its front. His wife stood at the open front window, white curtains blowing in on her while she arranged flowers in a silver bowl.

The house, No. 28 Hyde Park Gate, is on a narrow, treeless street that comes to a dead end and looks up at the streaked kitchen windows and television antennas of the backs of faded apartment houses.

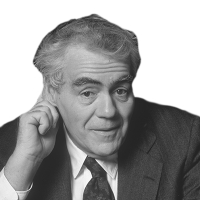

His voice once directed the affairs of continents and his words will move men forever, and he is of history. But only his family and doctors came to him yesterday. At ninety, Sir Winston Churchill is being allowed to die in the understatement and privacy by which his people live.

Sergeant Edmund Murray, of Scotland Yard, stands in front of the black doors and silver handles of No. 28. Murray, Winston Churchill’s bodyguard for fifteen years, has a mustache. He stood in the rain yesterday in a black derby hat, gray pinstriped suit and vest, and blue striped tie. His middle bulged against a brown tweed coat. He kept his right hand clamped over a pipe to keep it dry.

“Ups,” he said. “What’s this now?”

A woman in a raincoat and brown low-heeled shoes started to walk out of the small crowd. Murray’s eyebrows went up. The woman stopped and went back.

There were only nine uniformed policemen on the street, and they were unnecessary. A crowd of 150 reporters stood in the street as if they were in church. The rest of the people who came walked down the block in twos and threes and they would stand for a moment at a distance, looking at the brick house, and then they would leave, only to have others take their place. Every few minutes a boy carrying flowers, or a messenger bringing telegrams, would come up to the house.

“Ring the bell,” Murray told them. “They’ll answer.” They pushed the silver bell and the black door opened and a butler in double-breasted jacket and baggy pants opened it, took what they had, nodded thanks, then closed the door. The rest of London stayed away from Hyde Park Gate while Winston Churchill was dying yesterday.

“Why people have respect for tradition and procedure?” Murray was saying. “We’re a civilized country. The people won’t want to come here. They don’t want to be accused of morbid curiosity.”

Two houses up, a door opened and a man came out with a black and white cocker spaniel on a leash. He stopped and looked down at the sidewalk. A container of milk had been spilled there and the rain was spreading the milk all over the sidewalk in front of the house.

“Oh Lord,” the man said. He shook his head.

Two doors away, one of the great figures in the history of the world was dying. The man turned and walked the other way with the cocker spaniel.

This was Britain’s public face yesterday while it waited for Winston Churchill to die. The enormity of England without Churchill, even an ancient Churchill who had only short periods of lucidness each day in his last years, seemed to shake no one at Hyde Park Gate or Fleet Street or Mayfair or any of the other places in this city that are known.

It was different in the Crooked Billet. The Crooked Billet is a pub with three entrances to it on the corner of Cable Street, which is in the East End, and Cable Street is where the dock workers live. Yesterday afternoon, they came in and drank stout and rum and talked about Winston Churchill as they talk about a friend.

The Crooked Billet has a red tin ceiling and a round bar, cut into three separate small bars by ancient frosted glass partitions. In one of the bars, the men were standing in their overcoats at the bar and the old women, kerchiefs and cloth coats, sat at little three-legged tables.

“’Ow’s he now?” a man at the bar said.

“Not good.”

“Well, that name Churchill is respected everywhere,” he said.

“Did you ever meet him?”

“’E was around,” he said. “’E was around in the raids.”

“Did he ever say anything to you?”

“Ask that la-ty,” he said. He pointed to a heavy woman who sat at a table alone, her thick legs resting in front of a small gas heater. She had one hand wrapped around a black leather change purse. The other held a pint glass of stout.

“Moad,” he said.

“’E wants to ask you somethin’.”

“What do you want?” she said.

“Did you ever see Churchill?”

“’E saved our skins, why wouldn’t I have seen ’im?” she said.

“’E saved our skins for eighteen months,” one of the other women said.

“When did you see him?” Moad was asked.

“The Sunday raid,” she said. “When else would I see ’im?”

“When was that?”

“’Ow can I remember that? I’ve ’ad so much trouble, ’ow can I remember when it was. It was the Sunday raid, that’s what it was.”

“Was it bad?” She slammed her glass on the table. “Was it bad? Get away from me, was it bad. There were twenty-six of them dead at one turnin’ and one of them was my mother.”

“Where?”

“Where?” she snapped. “Under the archway. Right down the street. It was a shelter, only it collapsed and I stood with my three and watched them pull my mother out dead and I was standin’ there with my ’usband away and my mother dead and then Churchill came and he told us all. ’E said for every one they dropped ’e’d drop three on them and we knew ’e meant it and ’e was goin’ to do what ’e said. And ’e done it. I’ll never forget that Sunday morning.”

Her hand came out in a fist and she shook it and her face flushed and she told you again, “’E said ’e’d give them three for every one they dropped and ’e done what ’e said, just like I knew ’e would.”

“’E was there when ’e was needed,” another one of the women said.

“We’d a been lost without ’im,” the man said.

Then one of the other women said something and so did another one, and the man at the bar started talking and now Moad’s fist shook at the air again and here in this little bar, with over twenty years gone since anger was needed, the fire came into them again and now you could see just what kind of job this Winston Churchill did for his own when they needed him.

He lies dying in bed, with the brandy going to waste on a shelf and his mouth unable to hold a cigar and the blood spilling inside his head. And now, for the ages to come, everybody is going to be explaining his life.

I’m right with Moad, who sits in a pub twenty years later with her fist in the air and a snarl coming out of her mouth.

She puts it all together for you.