What happens when an orthodox Jew, a devout Muslim, and an orthodox Christian go behind the gates for 13 days?

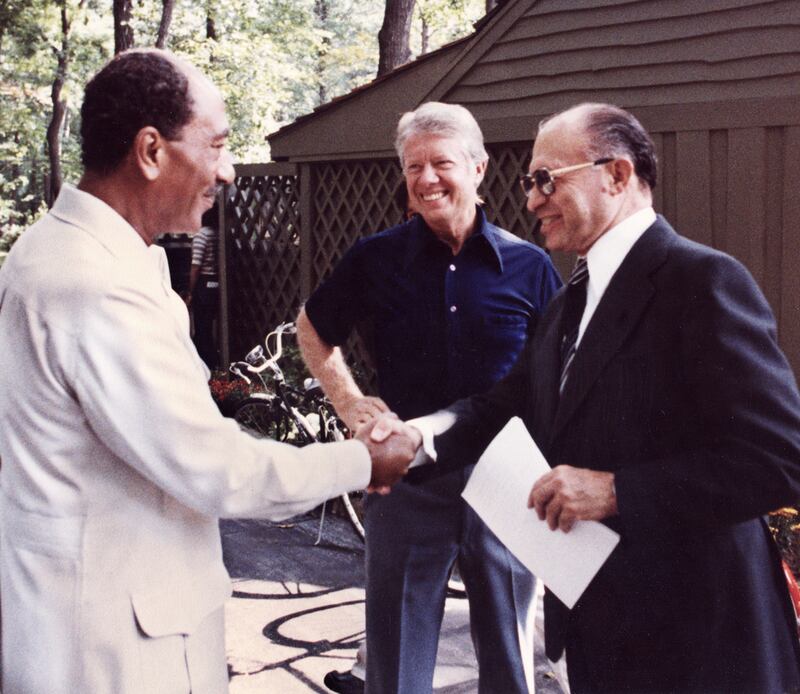

The punch line is they produced the only peace treaty that has stood the test of time. That’s how Jerry Rafshoon pitched the idea for an upcoming new play titled Camp David. He was there as the White House communications director when Jimmy Carter brought Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat to the Maryland retreat in September 1978, not knowing what the outcome would be—and in an exercise of presidential leadership, pulled off what the experts warned would be impossible.

“Carter gets accused of being too much involved in details,” says Rafshoon. “If he weren’t so detail-oriented, you wouldn’t have had a Camp David.” Carter has cooperated with the project, granting extensive interviews to scriptwriter Lawrence Wright, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Looming Tower. Camp David is expected to premiere at Washington’s Arena Stage late next year under the artistic direction of Molly Smith as part of its American Presidents Project. From there, who knows, it could be London, New York, maybe a Hollywood film.

Rafshoon first pitched the project as a movie soon after leaving the White House in 1980, but it didn’t happen, “wasn’t sexy enough,” he says. Seeing the play and then the movie, Frost/Nixon, reinspired him that an historical drama with a handful of characters could succeed. It’s a character study: the stately, ascetic Sadat took his meals by himself; Begin was more convivial and played chess with national-security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski.

Rafshoon and Wright traveled together to Israel and Egypt, interviewing everyone still living who was at Camp David in 1978 and gathering previously private anecdotes. Rafshoon discovered that everyone around Sadat advised him against signing the peace accords, but he went ahead anyway. The delegation accompanying Israel’s prime minister wanted him to sign, but Begin—who had been a freedom fighter for independence—resisted until the final hours.

“When we went through his papers, I could see what a gutsy man he turned out to be, going against all his instincts,” says Rafshoon.

Since leaving the White House after Carter’s defeat in 1980, Rafshoon has built a career as an Emmy-award winning producer. “If you liked Frost/Nixon the play and the movie, this has people you will like,” he says of Camp David. He insists it’s not a vanity project, that he hopes and expects it will be a commercial success. “This isn’t his idea, and it’s not being done to burnish Carter’s legacy, but it will,” Rafshoon told The Daily Beast.

As one of the Georgians who came to Washington with Carter, Rafshoon has been quick to rebut Mitt Romney’s constant characterization of Carter as a weak president, pointing out that Carter, in addition to taking a chance on peace in the Mideast, also authorized a hostage-rescue mission into the heart of Tehran that, while it failed, required courage on Carter’s part. Calling Romney “Carter’s polar opposite,” Rafshoon wrote in a column for Bloomberg News, “Scour Romney’s record for a single example of real political courage—a single, solitary instance, however small, where Romney placed principle or substance above his own short-term political interests. Let me know if you find one.”

The breakthrough at Camp David came nearly two weeks after what was an almost total news blackout. Carter had decreed no press, a dictum that Rafshoon and press secretary Jody Powell said would anger the media: “They’ll kill us,” they told Carter, who dryly said that they would be dying for a good cause and turned aside their protestations. Keeping the press in the dark turned out to be a smart decision, Rafshoon says, because of the roller-coaster nature of the talks, with a potential deal coming together more than once only to fall apart hours later.

Sadat and Begin weren’t even speaking much of the time after their initial encounters ended in heated arguments. Carter worked with the top aide each had designated, and then shuttled between the two leaders in a golf cart. Sunday morning, when all appeared lost, Carter personally delivered pictures to Begin inscribed to each of his grandchildren. “I wish I could put in there ‘when your grandfather and I brought about peace,'” Carter said, and Begin started to cry. Carter had broken through his defenses, and would later say of his relationship with the two men, “Begin didn’t trust me enough, and Sadat trusted me too much.”

When the deal was reached, Carter’s instinct was to let Secretary of State Cyrus Vance announce it at the State Department. No, this is yours, Rafshoon told him. It has to be primetime TV, and at the White House. “Do you think you can get on TV with this?” Carter asked, noting that the two framework agreements would have to be finalized. Rafshoon understood of course that in the world of Middle East diplomacy, this was big, and Marine One landed on the White House South Lawn carrying Carter, Begin, and Sadat for the Sunday, Sept. 17, 1978, announcement.

The Camp David Accords paved the way for the Israel-Egypt Peace Treaty, which was signed in March 1979. After leaving office in 1981, Carter remained engaged in the Middle East, sometimes drawing fire for speaking out against the Israeli practice of building settlements in the West Bank. He and his wife, Rosalynn, are currently in Egypt to monitor the presidential election.