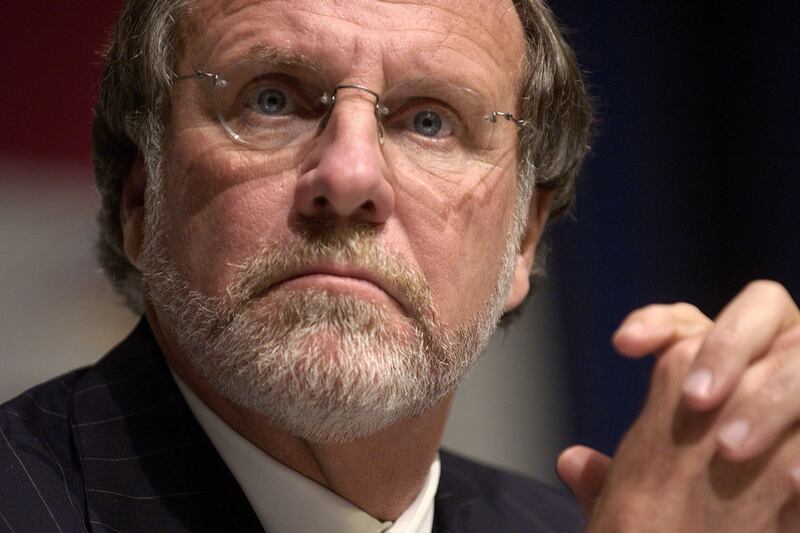

People who know Jon Corzine, the now ousted chief executive of the bankrupt brokerage MF Global, all say the same thing: Corzine is too honest to have committed any of the number of possible counts of securities fraud under investigation in the wake of the firm’s collapse on purpose.

They also say something else: Any brokerage with Jon Corzine at the helm is destined to fail.

Again, this is not because he’s a crook. It’s because he has almost no regard for simple management skills, and because of that almost anything he touches will eventually implode, including his career, say several people who know—and like—Corzine.

This assessment comes, of course, as Corzine announced Friday that he’s stepping down from the firm he destroyed, ending a long and distinguished career in politics and Wall Street in one of the worst possible ways. But this reckoning was foretold the moment the former New Jersey governor and chief executive of Goldman left politics after losing the statehouse in 2009 and landed at MF Global.

Corzine vowed to remake a small, backwater commodities broker into a mini-Goldman, where swashbuckling traders use all their global markets skill and acumen to make hugely profitable bets. The board of the firm loved the idea of MF Global as a mini-Goldman. One of MF Global’s biggest shareholders, J. Christopher Flowers, another Goldman alumnus, brought in Corzine and assured board members of the former governor’s skill and knowledge.

This approach had just two problems: First, Corzine was remaking MF Global in the image of a firm that doesn’t exist anymore. Goldman is no longer the swashbuckling trading shop that scored huge earnings for years. The Dodd-Frank financial reforms and the lessons of the financial crisis have squeezed out much of the firm’s risk taking.

Second, Corzine is possibly the world’s worst guy to run a trading shop where risk is the order of the day. Don’t take my word for it, just ask people who remember him from his days at Goldman. He was known as “Fuzzy,” and not because of his trademark beard.

“He was called ‘Fuzzy’ because he’s a sloppy thinker,” one Goldman executive who knows Corzine and has no ax to grind tells me. “You can never really figure out what he’s doing because he doesn’t know. He just kind of wings it.”

Corzine, says the executive, would engage in merger discussions without consulting other Goldman partners or board members, a huge no-no at any brokerage firm, much less a partnership like Goldman, where major decisions are debated and discussed. It didn’t end there. A former bond trader, Corzine would forget that his main job was to manage traders and often would walk over to the trading desk and take positions in the markets, of which some worked and others didn’t, according to former colleagues.

Indeed, he was ousted from Goldman because some trades he authorized didn’t work, particularly around the time the hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management collapsed in 1998. Goldman lost about $500 million on those trades, then an astronomical sum, and the way Corzine handled the episode led his colleagues to conclude that no matter how nice and well-meaning he is, he’s absolutely the wrong guy to have his finger on the button.

Fuzzy thinking and winging it might not lead to total disaster at a place like Goldman, which eventually worked its way out of the Long-Term Capital mess, but it could, and did, at a place like MF Global, a midsize brokerage firm where the CEO has a free hand.

“That’s why the meltdown didn’t really surprise me,” says another former colleague. “What happened is typical Corzine.”

That typical Corzine involves risk taking without analysis and consultation. Apparently, his firm ignored advice not to double down on the trades that eventually destroyed it, investments in the sovereign debt of Italy and Spain. Both countries’ debt was trading cheaply, and he had a gut feeling they would be bailed out.

What he didn’t think about long enough, or clearly enough, was that such bailouts are both messy and unpredictable. Even after the Bush administration began and Obama followed through on the huge bailout to save the U.S. financial system, the markets collapsed to historic lows. The situation in Greece is further proof that bailouts aren’t easy and Europe’s troubles aren’t over.

And neither are Corzine’s. He has hired a well-known white-collar attorney to deal with a number of investigations into his role in MF Global’s demise. One avenue being probed is whether Corzine misled investors by touting the company while its balance sheet was collapsing. He hasn't been charged with any crime; a call to his lawyer was not immediately returned.“Jon may be sloppy, but he’s not a liar,” a former Goldman executive tells me.

One bit of preliminary good news for Corzine is that fuzziness, not fraud, did in MF Global, according to the assessment of bankers who reviewed the firm’s books during the hours leading up the bankruptcy. At least on first glance, MF Global’s problems, including using customer money to complete trades, were the result of bookkeeping sloppiness rather than outright criminality.

And again, that doesn’t surprise the people at Goldman Corzine used to work with. As one friend and former colleague tells me: “He’s a wonderful man, a great guy, but this was bound to happen.”