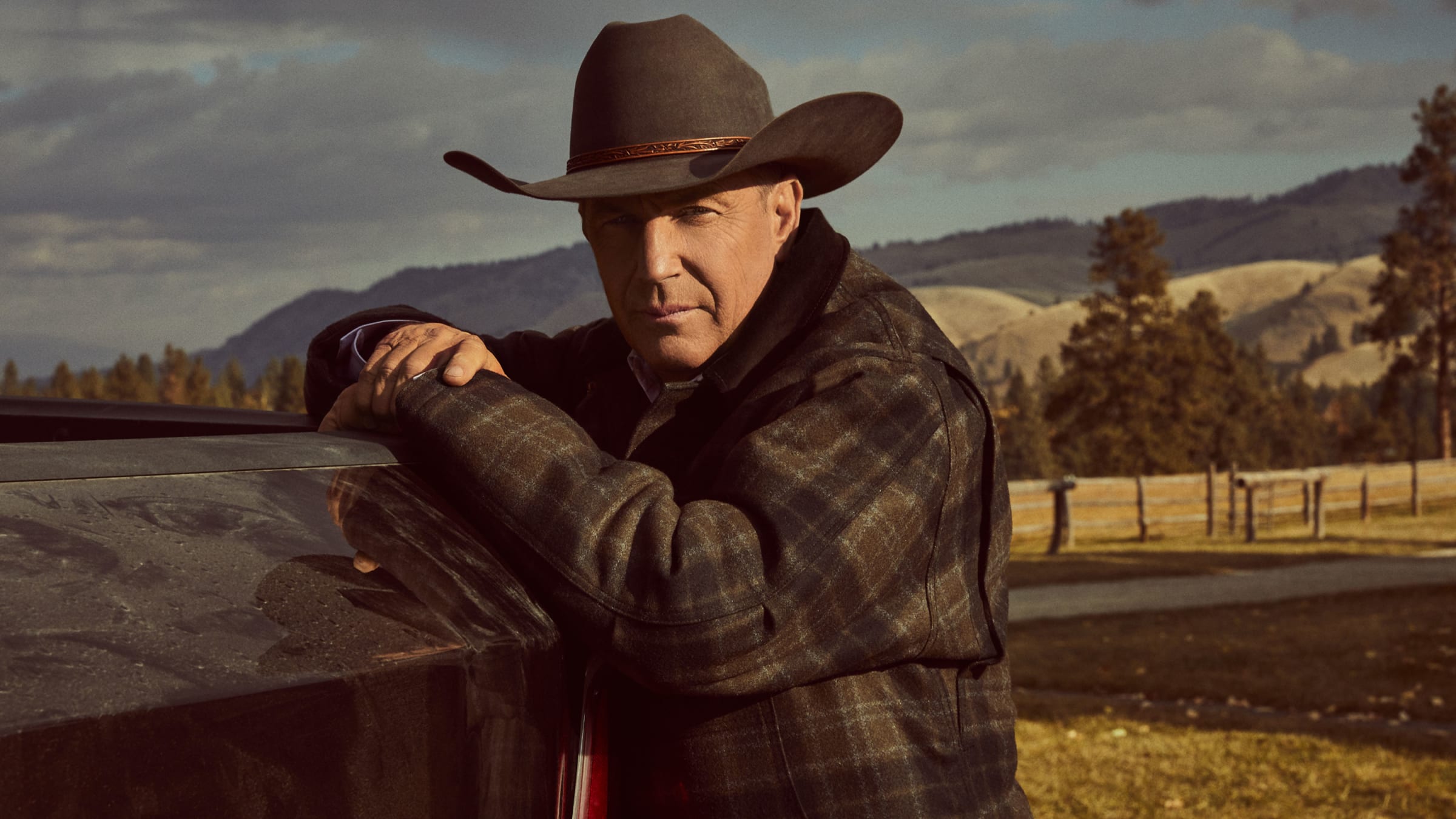

Kevin Costner on ‘Dangerous’ Trump, a ‘Bodyguard’ Sequel With Princess Diana, and American ‘Amnesia’

Paramount

The legendary actor and filmmaker opens up to Marlow Stern about his new travel app HearHere, Trump’s dismantling of the U.S. Postal Service, and his greatest hits.

He’s taken down Al Capone, erected a Field of Dreams, fought alongside Native American tribesmen, “solved” the JFK assassination, and saved Whitney Houston from an Oscar-night assassination. Now, screen icon Kevin Costner is exploring a different mode of storytelling.

The Oscar-winning actor and filmmaker is the co-founder of HearHere, a road-trip app that describes itself as a “hands-free experience that delights, informs and entertains by fostering a deeper connection with the people, places and histories of the land you are traveling through.” For example, you can hear Costner tell a story about the history of the Chumash Native Americans while cruising across the Central Coast.

“We don’t really know our history,” Costner, 65, tells me.

Costner, the laconic, effortlessly handsome everyman, is phoning me from Montana’s Bitterroot Valley, where he shoots his acclaimed Western TV series Yellowstone. And we managed to cover a great deal of territory over the course of our nearly hour-long chat, including his planned Bodyguard sequel with Princess Di, why he turned down Django Unchained, the removal of Confederate monuments, the chaotic state of America, and so much more.

I was watching The Late Show with Stephen Colbert last night, and they aired a segment about how America owes you an apology for the way it treated The Postman—given recent events.

[Laughs] Stephen Colbert said that? Did you ever see The Postman?

I did in theaters, yeah.

Oh, good. I liked making that movie. I did.

Do you feel sort of vindicated now given how prescient the film’s turned out to be?

Prophetic, you mean? [Laughs] You know, listen, a movie is what it is when it comes out, and it has a chance to be revisited. I was always kind of proud of it. I thought I probably made a mistake not starting the movie off saying, “Once upon a time…” Because it’s kind of like a fairy tale: “Once upon a time, when things got really rotten, the only thing that could stand the test of time was the Post Office. The only thing that people could count on.” I didn’t say that and I probably should’ve, because it is like a fairy tale that you’d read to your children at night. That’s how I did the movie.

It is crazy to see what’s going on right now with Trump’s systematic dismantling of the Post Office. Does it strike you as surreal?

It’s terrible. It’s terrible. Nothing is surreal—everything is highly real, and it’s dangerous, and it’s shameful.

With The Postman, I did very much enjoy the Tom Petty cameo.

It deals with the nature of fame, you know what I mean? It’s a very subtle thing. I think Postman actually is kind of a very funny movie, when you watch it. There’s humor wrapped all the way through it. Just dealing a little bit with the nature of fame, and dealing with somebody who’s famous, and him saying, “No, you’re famous.” That’s all the movie was trying to do.

With HearHere, what inspired you to create this platform?

Well, I can’t say that I created it. I can say that my wife [Christine Baumgartner] brought the idea to me. One of our children in preschool, this girl—who I think was a little more forceful—decided that [our son] Hayes was her boyfriend, and my wife knew her parents. That relationship, while it wasn’t cemented there, we met the parents there, and somewhere along the line they reconnected with my wife and wanted to know if I would be interested in this idea. I love the idea of stories and history, and went to it immediately from a historical bent, and made my participation a condition of that. As a founder, I said, “Look, we can’t talk about anything that’s here unless we’re willing to talk about anything that was here before anything else. And we need to continue to curate those stories.” Not everybody wants to know about history, I get that. But I love the history of America, and I love it when it’s the truth. It’s an ugly outcome but I feel it’s really important to know.

HearHere

The way we’re taught U.S. history is very strange. There is this extreme erasure of minority cultures—the Native Americans, especially.

It’s a dumbing-down. There’s usually one chapter and it’s not even skin-deep. So what happens, is our fingerprints on how America came to be are really interesting. It’s not always a pretty picture but it’s so wonderful to understand it, and only in understanding it can you develop an empathy, and can understand that we wiped out over 500 [Native American] nations. These stories aren’t designed to embarrass or make you ashamed—they’re designed to make you aware. And out of your awareness, you don’t have such a lofty opinion of what America is about versus what other countries are about. Most borders are formed in blood. In Europe, they were formed in blood. We did the same thing here, and we have some kind of national amnesia as to that truth.

There does seem to be strong hagiography when it comes to the history of the United States. I mean, you look at the twenty-dollar bill and there’s Andrew Jackson on there—and I know it’s supposed to be Harriet Tubman by now, though the Trump administration has for some reason blocked it.

Whoever goes on it goes on it. And getting rid of Jackson isn’t the point. The point is to understand who Andrew Jackson was—he was a fierce warrior in another century and a battle-tested, hard guy who rose to become president. But he also defied the Supreme Court, and he also took six great nations and moved them to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears. That’s his history. So how we look at him is how we look at him. How we want to judge him, that’s up to people. It’s difficult to judge somebody in another century. I’m not about judging somebody, I’m about: What did they actually do?

You can judge the Indian Removal Act though, right.

Well, let’s look at what he did and not erase them from history—but illuminate the history. To take six tribes, and the ignorance of thinking you could displace them? And the ignorance of doing that without even knowing that these tribes had their own historical differences, and then moving them to a place and telling them to share the land? That’s like putting the Crips and the Bloods in the same place. What would that be like? It’s our history. We don’t have to judge it; we have to understand what happened. And I find that to be the joy of what HearHere could be about. I’m caught up in history.

One of the big topics concerning history is the removal of Confederate monuments, and I know you tackled the Civil War a bit in Dances with Wolves, of course. What are your feelings on that? Because this stuff happened and we need to acknowledge it but we also don’t need to celebrate it with a monument.

Right. I think that’s probably where you go. You want to understand how the South was operating, and from the moment the Declaration of Independence was drafted, we couldn’t live up to it—we weren’t living up to it. And while very intelligent men were drafting it, women weren’t drafting it, and the only people who could vote were people with property. Women couldn’t vote, Native Americans couldn’t vote, Black people couldn’t vote, people without property couldn’t vote. America is an idea, and we have a chance to live up to it. And we haven’t done it.

And that’s what we’re experiencing now. We’re not willing to do the work as a nation to do the hard thing, which is to understand that this plague—this epidemic—could get out of hand, and that’s bigger than all of us. It’s exposing our ability to care about each other across lines and borders. We’re exposed. And I think we look weak to other countries because we don’t put others in front of ourselves, and when we marginalize people like we did—enslave them—we never recovered from that. So the idea of the statues, I don’t think they’re appropriate.

You mentioned the coronavirus, and I agree, it does seem to be exposing America’s lack of community, lack of selflessness, and lack of reciprocal altruism.

We haven’t done it. And it’s apparent. And it’s apparent to everybody around the world. There are societies that are dictatorial that say, “Everybody do this and everybody bow down,” and thank God we’re not that, but for us to see the handwriting on the wall of what this is and what this continues to be, and the shading of the truth and the distortions of it—the false exaggerations of what we are doing—are so transparent that we need to take stock of ourselves. There are individuals that are placing their careers above the national good. And we need to remember if they’re right, and they haven’t been right about anything when it comes to [coronavirus].

Paramount

It does seem like you’re talking about Trump here.

I’m not just talking about him. I’m talking about anybody in politics. You can look at him, and you can look at all the senators and congressmen. Public service isn’t about your second term—it’s about the moment, and you’re supposed to let history judge it. When you go into public service, you should work so hard on behalf of the public that you don’t wanna serve a second fuckin’ term! You should be like, “I hate this! I hate having to go out there and do this.” And if you’re really good, the people won’t let you go. They’ll say, “You’re really good at this. You should stay.” Public service should be an everyday thing when that’s what you choose to make your life. It cannot be about your second term.

There’s no point in naming names because they’ve been outright about it but: history will judge you. When you look back at [Joseph] McCarthy, when you look back at black-and-white footage and see people who were beating on those who were marching for freedom, you don’t want to be that person. And there’s a lot of people where, when you look back 10 years, they’re going to see themselves. And it’s patently obvious where we should be, and it’s patently obvious where we are.

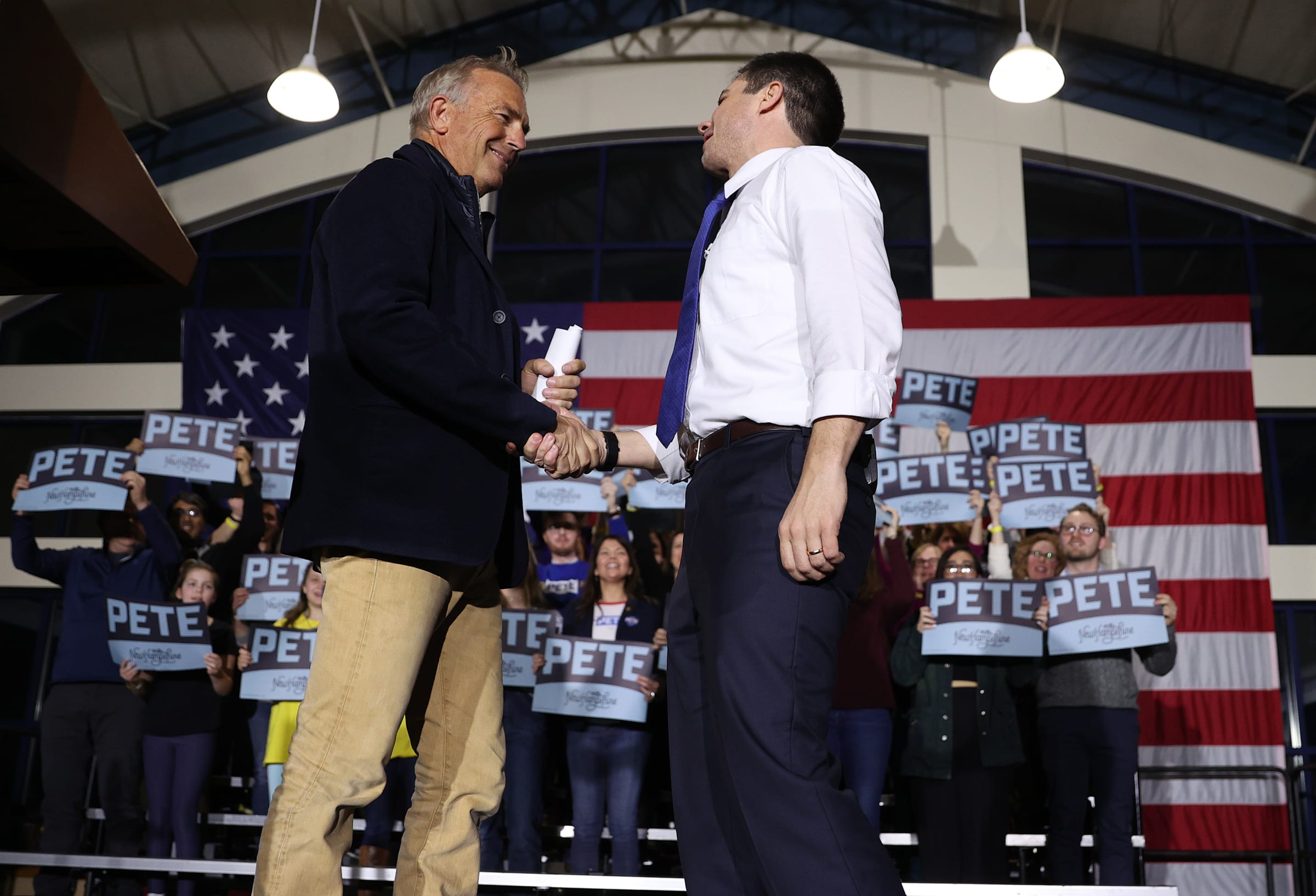

I know you came out for Pete Buttigieg on the campaign trail. How do you think the Dems are looking now?

I don’t want to go down that road. That’s who I supported. I’m an independent. I vote for who I think has the best interests of the country and how we sit in the world. That’s who I supported, and I’m going to vote. I felt that Pete, among two or three others—I won’t name them—but I thought that he had the best vision for how we move forward, and had the best energy. And for everybody who said, “Oh, the country’s not ready,” look where we’re at. The best idea wins, and so that’s why I supported him. I felt this was a man who had leadership capabilities and a vision. I don’t do that every election, come out for someone. And I did come out for him. I came out for Barack Obama too. Who I vote for is a private issue—unless I come out.

Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg arrives on stage after being introduced by actor Kevin Costner at a Get Out the Vote rally at Exeter High School on February 10, 2020, in Exeter, New Hampshire.

Win McNamee/Getty

You were often pegged as a “Republican actor” in the late-‘80s and early-‘90s by the press.

Yeah—and I didn’t even answer back on that. I just didn’t even answer back on that. I think it was because of the movies I was doing, but I never said one thing or another. I really go back and forth on my votes. The Democratic Party doesn’t represent everything that I think, and neither does the Republican Party right now—at all. So, I find it too limiting.

If someone is lying to their base, lying to the general public, then they’re not serving any purpose—other than for themselves. What’s probably frustrating is trying to play by the rules when someone isn’t playing by them. That’s what people can’t get their arms around. What you have to try to lean on is that every four years we get to decide whether we’re going in the right direction or we’re not. And we now, because of the way the country is set up—which is beautiful—we have that opportunity. And anyone who would interfere with that process in a deliberate way to have an outcome—that’s criminal. And it spits on 200 years of freedom.

And that seems to be what’s going on with the Postal Service right now.

Well, this is what you do: you wear your mask, and you go vote. You find that polling place, and you go vote. I saw a really interesting poster, the way that only advertisers can do it in such few words—that’s the reason why my movies are three hours long, it’s an art form. It was in New York, and it probably had to be 15 years ago, and it said, “93 million people made a difference this year—they didn’t vote.” So, it rests with us. Just like COVID and just like everything, we’ve lost a sense of ourselves, but we can try to gather it back by just simply voting. If you like the direction of the country then that’s what you vote for, and if you don’t, you vote for something new.

I’m obsessed with movie trivia and what could have been. To bring it back to The Postman for a second, I’d read that because you were so busy on Postman you had to turn down Air Force One? And then you suggested Harrison Ford?

That’s right. But you know, he was a very popular actor and I just suggested him. It’s not that they might not have ended up thinking of him, but I just said, “I’m not going to do that and I think Harrison would be great at it.” That’s all! It’s not a big deal to me.

I’d also read that you’d turned down the Bill role in the Kill Bill movies, and that Quentin Tarantino has been trying to work with you for a bit.

That’s not true—but I would like to work with him, and we just haven’t found that thing. We almost worked together in Django but it was not something that I wanted to do. I turned around and made a movie called Black or White. Me and my wife paid for that ourselves to make that movie. I liked the message about racism in that particular movie.

So you took issue with the way Django Unchained portrayed race?

No, not issue, you just have to make up your mind about what you want to do, and I’d still like to work with Quentin. But I always find that when you work together on the right movie, that’s when it’s right—not just because you admire somebody’s filmmaking. I’d like to work with Paul Thomas Anderson too, and a lot of people, but it has to be the role that makes sense. And then it becomes wonderful. You have to know when you’ll actually be able to help them, and be able to play that part.

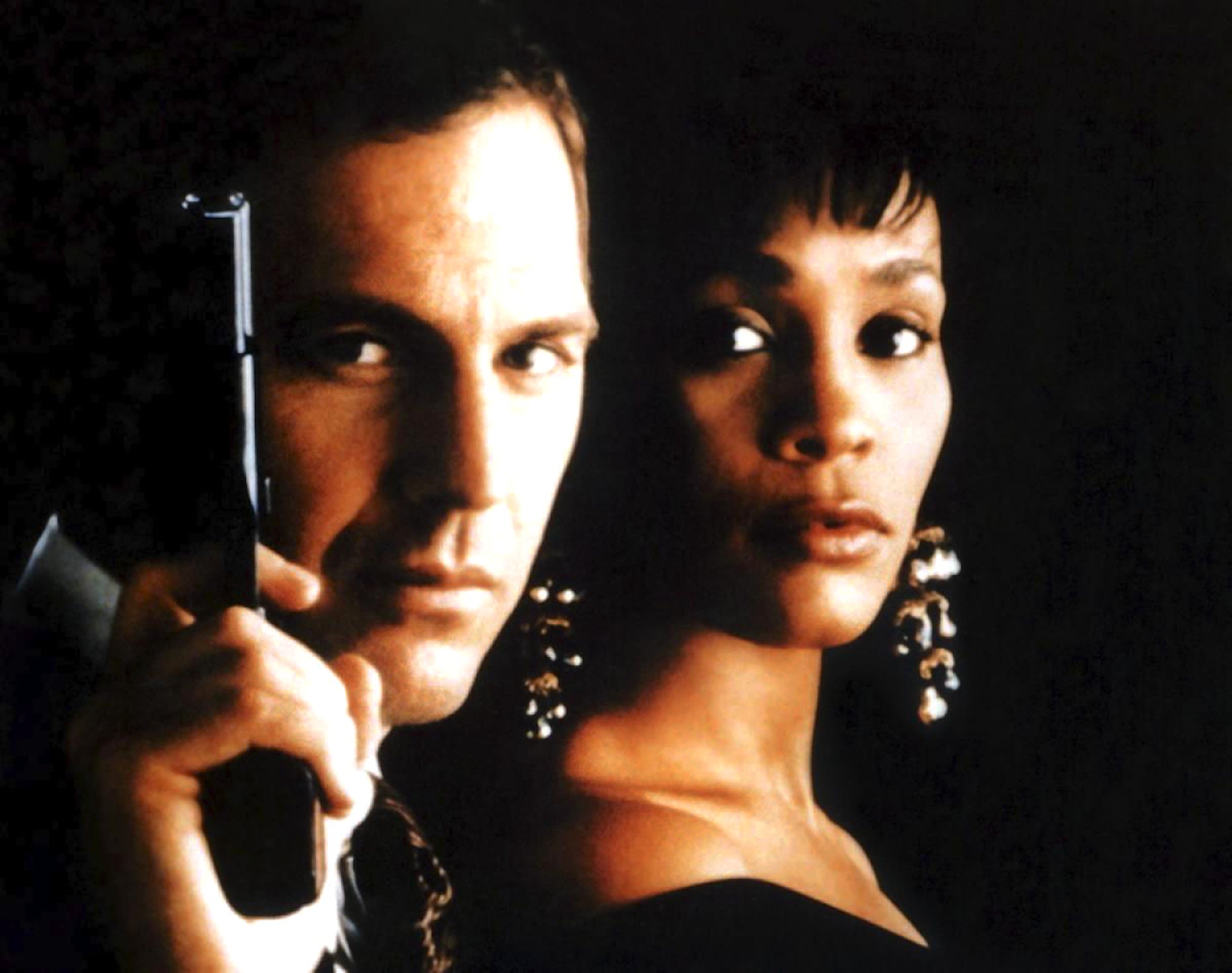

Me and my girlfriend re-watched The Bodyguard during lockdown, and that movie still holds up incredibly well.

Like The Postman? [Laughs]

Kevin Costner and Whitney Houston in The Bodyguard

Warner Bros.

[Laughs] It seems to gain more cultural relevance with each passing year, and I’d read that you were quite instrumental in casting Whitney Houston. What about her jumped out at you during auditions?

Yeah, that’s correct. Well, we were talking about a world-class talent—in terms of this guy protecting a world-class talent, and world-class singer—and this guy is on record not wanting to protect celebrities. When you do a baseball movie, you should pick people who actually know how to play baseball. [Laurence] Olivier might be our greatest actor or Daniel Day-Lewis might be, but if they couldn’t play baseball, they can’t out-act that. They can’t do it. It’s a weird thing. I’m not saying they can’t play, I’m just saying it doesn’t matter how good an actor you are. So, if you’re going to have a world-class singer, I just felt that if we got an actress that looked beautiful that couldn’t sing it would work, but I felt the actress that could sing and who’d never been in a film could have a much stronger impact on the movie. I saw Whitney as a beautiful woman and a world-class singer, I saw the fit, and I wouldn’t take anything less.

There were rumors about a sequel to The Bodyguard featuring you and Princess Diana.

Yeah. Well, that’s the truth.

And it would have been you protecting Princess Di?

That’s how it would have worked if she’d have done it. We had conversations about it. It was going to be in Hong Kong, and you can see how scary that would have been, and it would have played into all that stuff.

Wow. That would have been something. And it’s crazy how things turned out, given those talks.

Yeah...

Paramount

I’m a Yankees fan, and I understand the big game at the Field of Dreams field has been pushed back to 2021. You’ve gotta be throwing the first pitch at that, right?

Yeah, there’s a lot of talk about that. I don’t like throwing out first pitches! I’d like to hit the first homer there. [Laughs] There’s so much pressure around first pitches. I’d much rather play in the damn game than throw a single pitch!

There’s always been speculation about who The Voice is in Field of Dreams. The rumor is that it’s voiced by Ed Harris, Amy Madigan’s husband.

If I had to guess, I would say it’s the writer and director. I never asked him, but if I would have to guess, I would say it’s Phil Alden Robinson. That would be my guess. It sounds like that to me but I’ve never thought to ask him.

Did you ever see the Wayne’s World 2 parody of Field of Dreams, with Jim Morrison telling Wayne and Garth to erect a concert festival in Aurora, Illinois?

[Laughs] I didn’t! I guess Drake has a song now too [“Popstar”] where my name comes up about bodyguards or something. You know it’s…really something. [Laughs]

As far as Dances with Wolves goes, I’d read a funny story about how you borrowed buffaloes from Neil Young for the big buffalo hunt sequence. Is that true?

We used one of his buffaloes, yeah. He only had one. We needed a buffalo because we didn’t herd any animals, but we needed a tame buffalo because we wanted to stick arrows on him and let him run with the rest of the buffalo, and he was afraid of the rest of the buffalo, so when they took off running he took off running too and we would chase him, and we acted like we shot those arrows into him—and that was Neil Young’s buffalo. [Laughs] Neil Young is a beautiful guy.

There have been criticisms of Dances with Wolves over the years—that it’s a “white savior” film. How do you feel about those critiques?

Well, it wasn’t a story about the Native American people—it was a story about this guy. That’s what people keep confusing. It was a story about this cavalry guy who ultimately had to interact with them, and I just made them as human as I possibly could. It was a white guy’s story set against theirs, and it was a single story. I made a nine-hour documentary called 500 Nations, so I don’t have to answer critics about that. You get criticized about making a story about Native Americans and they say, “Well, you’re not Native American so you’re not entitled to make a story about them.” I get what they’re saying but that’s an easy stance. This is somebody who wanted to integrate into them, and the idea of “savior” is because [Native Americans] didn’t have the technology, so there was a contrivance by the writer that there was an abandoned fort that they could use to protect themselves. So, I don’t get caught up in that. The people that do should make stories themselves.